Dolly Sods Wilderness: Difference between revisions

imported>Chris day (→History: now the high quality picture is uploaded will need to reduce space) |

imported>Kris Herbst No edit summary |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

[[Image:sodstream.jpg|thumb| | [[Image:sodstream.jpg|thumb|400px|Upper Red Creek area of Dolly Sods Wilderness by [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Dolly-Sods-Red-Creek.jpg Knotnic]]] | ||

The Dolly Sods area was first explored by Thomas Lewis during a survey in 1746 to find the limits of Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron’s land grant from the British Crown. Lewis’ journal provides the earliest written record of the area’s natural condition: | The Dolly Sods area was first explored by Thomas Lewis during a survey in 1746 to find the limits of Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron’s land grant from the British Crown. Lewis’ journal provides the earliest written record of the area’s natural condition: | ||

Revision as of 21:39, 27 March 2007

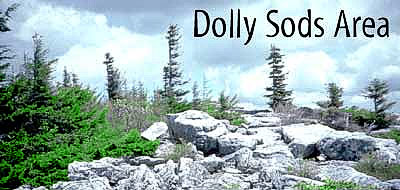

The Dolly Sods Wilderness is a U.S. Forest Service wilderness area in the Allegheny Mountains of eastern West Virginia, USA and is part of the Monongahela National Forest.

In 1970, 10,200 acres of the Sods were designated a National Forest Scenic Area. The Dolly Sods Wilderness was made a part of the National Wilderness Preservation System on January 1, 1974 with the passage of the "Eastern Wilderness Act." It is designated as a Category Ib-Wilderness by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) .

Geography

Dolly Sods is the highest plateau of its type east of the Mississippi River with altitude ranging from around 4,000 foot (1,200 meter) at the top of a mountain ridge on the Allegheny Front to about 2,700 feet (820 m) at the outlet of Red Creek. The highest point in this immediate area is Mount Porte Crayon, at 4,770 feet (1,454 m), in Flatrock-Roaring Plains.

Dolly Sods lies at at latitude 38° 59' 45"N (38.996°), longitude 79° 22' 5"W (-79.368°) on a ridge crest that forms part of the Eastern Continental Divide. Most of its area is drained by Red Creek, which is a tributary of the Dry Fork River; via the Dry Fork, Black Fork, Cheat, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers, it is part of the Mississippi River drainage watershed. Drainage on the east side of the ridge crest flows into the headwaters of the South Branch of the Potomac River, which is part of the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

The 10,215-acre Dolly Sods Wilderness is only part of the 32,000-acre area known as Dolly Sods. It is bordered by a Forest Service road on the east and south side. South of this road is the adjoining Flatrock-Roaring Plains area (which is drained by the South Fork of Red Creek). The northeast end of the Federal land at Dolly Sods is bordered by the Bear Rocks Nature Preserve, owned by The Nature Conservancy.

In 1991, 6,168 acres north of the Wilderness and west of the Scenic Area were purchased and dubbed "Dolly Sods North." It is a backcountry access area though not designated wilderness. The West Virginia Wilderness Coalition proposes Congressional Wilderness designation for both the Dolly Sods North area and the Roaring Plains area. This northern section of Dolly Sods is a wind-swept high-elevation plateau that is boggy. It is generally open with wide-spreading vistas. Huckleberries and cranberries are common in the heath and bog areas. Patches of native red spruce, alder, maple, and mountain ash mingle with plantations of pine, upland heath, and sphagnum bogs.

Most of Dolly Sods is in Tucker County, West Virginia. Small parts of Dolly Sods are also in Randolph and Grant Counties, West Virginia.

History

The Dolly Sods area was first explored by Thomas Lewis during a survey in 1746 to find the limits of Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron’s land grant from the British Crown. Lewis’ journal provides the earliest written record of the area’s natural condition:

- ". . . the swamp, (which is very uncommon in places of ye kind) is prodigiously full of rocks and cavities, those covered over with a very luxuriant kind of moss of a considerable depth. The fallen trees, of which there was great numbers and naturally large, were vastly improven in bulk with their coats of moss. The Spruce pines of which there are great plenty, their roots grow out on all sides from the trunk a considerable height above the surface, covered over and joined together in such a manner as makes their roots appear like slimey globs. The Laurel and Ivy as thick as they can grow whose branches growing of an extraordinary length are so well woven together that without cutting it away it would be impossible to force through them . . . from the beginning of the time we entered the swamp I did not see a plane big enough for a man to lie on or horse to stand . . . Never was any poor creature in such a condition as we were in, nor ever was a criminal more glad by having made his escape out of prison as we were to get rid of those accursed laurels."

The area was generally avoided as too impenetrable until the late 1800’s. David Hunter Strother wrote an early description of the area, published in Harper's Monthly magazine in 1852:

- "In Randolph County, Virginia, is a tract of country containing from seven to nine hundred square miles, entirely uninhabited, and so savage and inaccessible that it has rarely been penetrated even by the most adventurous. The settlers on its borders speak of it with a sort of dread, and regard it as an ill-omened region, filled with bears, panthers, impassable laurel-brakes, and dangerous precipices. Stories are told of hunters having ventured too far, becoming entangled, and perishing in its intricate labyrinths. The desire of daring the unknown dangers of this mysterious region, stimulated a party of gentlemen . . . to undertake it in June, 1851. They did actually penetrate the country as far as the Falls of the Blackwater, and returned with marvelous accounts of its savage grandeur, and the quantities of game and fish to be found there."

The extensive high areas in Dolly Sods and Flatrock-Roaring Plains were once mostly covered by dense, ancient Red Spruce and hemlock forest. The trees were 60 to 90 feet tall (18-27 m) and some measured at least 12 feet (370 cm) in diameter. The greatest stand of red spruce in the world, in terms of size and quality, could be found along the upper Red Creek. The largest recorded tree ever cut in West Virginia was a white oak, harvested in this region. Nearly as large as a Giant Sequoia, it was probably well over 1,000 years old and measured 13 feet in diameter at a height of 16 feet, and 10 feet in diameter 31 feet above the base. We will probably never know how large the biggest trees in West Virginia were because the cuttings were not documented. Centuries of accumulated needles from these trees created a blanket of humus (soil) seven to nine feet deep.

Logging began as early as the 1850s and by the late 1880s, railroad logging made the spruce and hemlocks accessible and the huge trees were cut down. In 1902, a band saw mill was built at Laneville, WV, with a railroad from the Dry Fork to service it. Shay locomotives climbed the mountain and logging camps sprang up throughout Dolly Sods, clearing away the virgin forest to feed hungry mills. The humus dried up when the protective tree cover was removed. Sparks from railroad locomotives, saw mills and logger's warming fires easily ignited this humus layer and the extensive slash (wood too small to be marketable, such as branches and tree crowns) left behind by loggers. Forest fires repeatedly ravaged the area, scorching everything right down to the underlying rocks. All insects, worms, salamanders, mice and other burrowing forms of life perished and the area became a desert. The destruction was extraordinary. it is estimated that in some areas, as much as six feet of organic topsoil was lost. More than one-tenth of the area of West Virginia state was burned over, including one-fifth of the forest area. By 1920, very little virgin forest remained in West Virginia. The complete clearcut of this ecologically fragile area, followed by extensive wildfires and overgrazing, as well as the ecological stresses of the elevation, have prevented quick regeneration of the forest.

The name Dolly Sods derives from the family name Dahle, a German family who homestead the logged areas, clearing and farming them. Burning the logged areas produced good grass cover for grazing sheep, and these open fields were known as "sods." Locals changed the spelling to "Dolly" and thus the area became known as the Dolly Sods. Repeated burning killed the grass and left only bracken fern, which was useless as fodder. The Dahle family eventually moved on, leaving behind only the Americanized version of their name.

After heavy rains in 1907 caused devastating erosion and flooding, Congress passed the Weeks Act in 1911. It allowed the federal government to purchase private land in the East for the national forest system -- with cooperation from state governments that desperately needed help to stop the cycle of fire, erosion and flooding downstream of the logged lands. The purpose was to restore denuded forests, stop flooding and secure sources of clean water. The act established the Monongahela National Forest, of which Dolly Sods is a part. Most of the lands now called Dolly Sods were acquired by the federal government between 1916 and 1939 under Weeks Act authority.

Reforestation efforts by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) during the 1930’s established red pine and spruce plantations on about 727 acres. The CCC’s also built the roads that now cross the area.

Beginning in August of 1943, in a cooperative agreement with the army, the area was used as a practice artillery and mortar range and maneuver area before troops were sent to fight in World War II. Artillery and mortar shells shot into the area for practice still exist there. In 1997, a crew surveyed the trail locations and known campsites for shells. They found 15, some of which were still live. All were exploded on site. See link for a photo of two shells found in July 2006.

Ecology

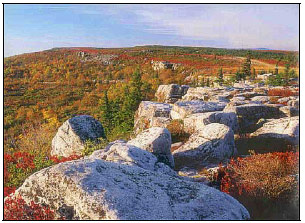

Today, there are patches of recovering native red spruce forest plus twisted yellow birch, alder, maple, hemlock, black cherry and mountain ash trees amid a matrix of heath-type bushes. Views across the tundra-like windswept open meadows in the northern section of Dolly Sods are reminiscent of Alaskan landscapes.

The heath vegetation increased due to the thinner soil. Timber cutting on the plateau may have caused the water table to rise, since there were no longer huge trees drawing water in and releasing it to the air. This increase in surface water restricted the growth of new forests and expanded the bogs. The whole area is largely colonized by various Ericaceae (heaths): blueberry and cranberry (Vaccinium), huckleberry (Gaylussacia), azalea and rhododendron (both in the genus Rhododendron), mountain laurel (Kalmia), and teaberry (or wintergreen, Gaultheria). The upper sections of Red Creek and its tributaries display sphagnum bogs, complete with rare sundew and reindeer moss.

Bogs are extensive on the sods due to abundant precipitation: the Sods averages more than 100 inches of snow each winter. During the winter of 2003, 290 inches (7.3 m) of snow fell in the area, although 160 inches (4 m) is more typical. The Allegheny Front that forms the eastern edge of the plateau is a ridge that catches and holds storms. In the high spots you can see how the red spruce have been sculpted by the wind – strong winds blowing continuously from the west have caused some trees to have branches only on the east side (they are "flagged").

Because of the high altitude the climate is cool, and plants and animals are more similar to ones found about 1,600 miles farther north in Canada. Many species found here are near their southernmost range. For example, the snowshoe hare found in Dolly Sods is usually found in Canada and Alaska and is adapted to snow conditions, with its large, hairy feet which allow it to run on the snow surface. Other animals include red and gray foxes, bobcats, black bears, turkey, grouse, and white-tailed deer.

Hemlock is a common conifer in the lower reaches of Red Creek and its tributaries, and rhododendron and mountain laurel clog the drainages. There are trout in Red Creek. Severe floods, often caused by east coast hurricanes, ravished the lower elevations and scoured the canyon bottom numerous times, most recently in 1985, 1992, 1994, and 5 times in 1996, ending with hurricane Fran. This changed the nature of Red Creek from a quiet stream of beaver ponds and lush vegetation to its current look of tumbled rocks and deadfalls.

Recreation

Dolly Sods is particularly popular during mid-summer with people who go there to pick blueberries and huckleberries.

There is an extensive network of hiking trails. Some follow old logging railroad grades, and occasionally you see some remnants of railroad ties and metal equipment. Trails do not have blazes and may or may not have signs. Large rock cairns will mark major trail junctions, and smaller cairns may mark areas where the trail location is confusing. No bridges are provided over streams. Until a 2004 remapping, the USGS and US Forest Service maps of the trails were inaccurate so a mapping site provides good maps with GPS data.

The Spruce Knob-Seneca Rocks National Recreation Area is adjacent to Dolly Sods-Flatrock-Roaring Plains on the east and the south.

External links

- National Forest Web site

- West Virginia Wilderness Coalition

- Potomac Appalachian Trail Club page

- Jonathan Jessup photos

- Wilderness.net

- Topozone

- Hikesite - MNF Trail information

- Dolly Sods Forest Walk at Forests of the Central Appalachian Project