Korematsu v. United States: Difference between revisions

imported>Larry Sanger No edit summary |

imported>Yi Zhe Wu (→Background: camp image) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

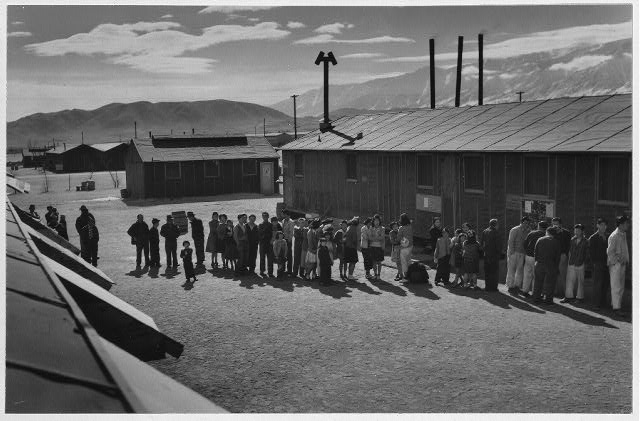

[[Image:Japaneseinternment.jpg|An internment camp in California]] | |||

When the United States entered the World War II after the attack on [[Pearl Harbor]], President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] issued an [[executive order]], numbered [[Executive Order 9066|9066]], that mandated the incarceration of Americans of [[Japanese]] descent into [[internment camp]]s. The program was termed by the government as "relocation". The reason of the order was that FDR feared the Japanese-Americans would have questionable loyalty and might conduct espionage against the United States, despite that no evidence had suggested such espionage. In total, about 110,000 men, women, and chilfren were incarcerated by the "relocation" program. | When the United States entered the World War II after the attack on [[Pearl Harbor]], President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] issued an [[executive order]], numbered [[Executive Order 9066|9066]], that mandated the incarceration of Americans of [[Japanese]] descent into [[internment camp]]s. The program was termed by the government as "relocation". The reason of the order was that FDR feared the Japanese-Americans would have questionable loyalty and might conduct espionage against the United States, despite that no evidence had suggested such espionage. In total, about 110,000 men, women, and chilfren were incarcerated by the "relocation" program. | ||

Revision as of 16:07, 1 May 2007

Korematsu v. United States was a controversial United States Supreme Court case, decided in 1944, that upheld the Japanese internment during the World War II. This case has been cited as an unprecedented erosion of individual liberties and racial prejudice during wartime in United States.

Background

When the United States entered the World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order, numbered 9066, that mandated the incarceration of Americans of Japanese descent into internment camps. The program was termed by the government as "relocation". The reason of the order was that FDR feared the Japanese-Americans would have questionable loyalty and might conduct espionage against the United States, despite that no evidence had suggested such espionage. In total, about 110,000 men, women, and chilfren were incarcerated by the "relocation" program.

When the United States entered the World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order, numbered 9066, that mandated the incarceration of Americans of Japanese descent into internment camps. The program was termed by the government as "relocation". The reason of the order was that FDR feared the Japanese-Americans would have questionable loyalty and might conduct espionage against the United States, despite that no evidence had suggested such espionage. In total, about 110,000 men, women, and chilfren were incarcerated by the "relocation" program.

Litigation

Fred Korematsu was a Japanese-American who refused to comply with the internment order and sued the United States government, arguing that the executive order violated due process and was racially motivated.

Decision

The Supreme Court decided in favor of the U.S. government and upheld the internment of Japanese-Americans. In a 6-3 decision, Justice Hugo Black wrote that the necessity to protect United States from espionage outweighed Korematsu's civil liberties, and said the internment was not racially motivated. Justice Felix Frankfurter authored a concurrence.

Three justices, Owen Roberts, Robert Jackson, and Frank Murphy each filed a separate dissent. Murphy's dissent was especially scathing, with the famous word that the majority decision "falls into the ugly abyss of racism".

Aftermath

Today, this decision is widely criticized and denounced as a classic example of wartime encroachment of civil liberties. The Congress passed Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act to provide compensation to Japanese properties damaged during the "relocation". In 1980 the Congress opened an investigation to the internment program and a report titled "Personal Justice Denied" was written. The report condemned the "relocation" and the Korematsu court decision. In 2001, the PBS broadcast a Eric Paul Fournier film Of Civil Wrongs and Rights in memory of the Japanese internment and the litigation of Korematsu. In 1998, Fred Korematsu was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton. Korematsu died in 2005.

Tom Clark, the coordinator of the relocation program, later became a Supreme Court justice and regretted his role in the Japanese internment and referred to it as one of his biggest mistakes.