Latin America: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

imported>Caesar Schinas m (Bot: Delinking years) |

||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

The region was home to many indigenous peoples and advanced civilizations, including the [[Aztecs]], [[Toltecs]], [[Caribs]], [[Tupi]], [[Maya peoples|Maya]], and [[Inca]]. The [[golden age]] of the [[Maya civilization|Maya]] began about 250, with the last two great [[civilization]]s, the Aztecs and Incas, emerging into prominence later on in the early 14th century and mid-15th centuries, respectively. | The region was home to many indigenous peoples and advanced civilizations, including the [[Aztecs]], [[Toltecs]], [[Caribs]], [[Tupi]], [[Maya peoples|Maya]], and [[Inca]]. The [[golden age]] of the [[Maya civilization|Maya]] began about 250, with the last two great [[civilization]]s, the Aztecs and Incas, emerging into prominence later on in the early 14th century and mid-15th centuries, respectively. | ||

With the arrival of the Europeans following [[Christopher Columbus]]'s voyages, the indigenous elites, such as the Incans and Aztecs, lost power to the Europeans. [[Hernán Cortés]] destroyed the Aztec elite's power with the help of local groups who disliked the Aztec elite, and [[Francisco Pizarro]] eliminated the Incan rule in Western South America. European powers, most notably [[Spain]] and [[Portugal]], colonized the region, which along with the rest of the uncolonized world was divided into areas of Spanish and Portuguese control by the [[Line of Demarcation]] in | With the arrival of the Europeans following [[Christopher Columbus]]'s voyages, the indigenous elites, such as the Incans and Aztecs, lost power to the Europeans. [[Hernán Cortés]] destroyed the Aztec elite's power with the help of local groups who disliked the Aztec elite, and [[Francisco Pizarro]] eliminated the Incan rule in Western South America. European powers, most notably [[Spain]] and [[Portugal]], colonized the region, which along with the rest of the uncolonized world was divided into areas of Spanish and Portuguese control by the [[Line of Demarcation]] in 1493, which gave Spain all areas to the west, and Portugal all areas to the east (the Portuguese lands in America subsequently becoming Brazil). By the end of the 16th century, Europeans occupied large areas of Central and South America, extending all the way into the present southern United States. European culture and government was imposed, with the Roman Catholic Church becoming a major economic and political power, as well as the official religion of the region. | ||

Diseases brought by the Europeans, such as [[smallpox]] and [[measles]], wiped out a large proportion of the indigenous population, with epidemics of diseases reducing them sharply from their prior populations. Historians cannot determine the number of natives who died due to European diseases, but some put the figures as high as 85% and as low as 20%. Due to the lack of written records, specific numbers are hard to verify. Many of the survivors were forced to work in European plantations and mines. [[Intermarriage]] between the [[indigenous]] peoples and the European colonists was very common, and, by the end of the [[colonial period]], people of mixed ancestry (mestizos) formed majorities in several colonies. | Diseases brought by the Europeans, such as [[smallpox]] and [[measles]], wiped out a large proportion of the indigenous population, with epidemics of diseases reducing them sharply from their prior populations. Historians cannot determine the number of natives who died due to European diseases, but some put the figures as high as 85% and as low as 20%. Due to the lack of written records, specific numbers are hard to verify. Many of the survivors were forced to work in European plantations and mines. [[Intermarriage]] between the [[indigenous]] peoples and the European colonists was very common, and, by the end of the [[colonial period]], people of mixed ancestry (mestizos) formed majorities in several colonies. | ||

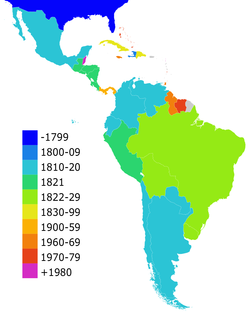

By the end of the 18th century, Spanish and Portuguese power waned as other European powers took their place, notably Britain and France. Resentment grew over the restrictions imposed by the Spanish government, as well as the dominance of native Spaniards (Iberian-born ''peninsulares'') over the major [[institution]]s and the majority population, including the Spanish descended [[Spanish Criollo peoples|Creole]]s (''criollos''). [[Napoleon I of France|Napoleon]]'s invasion of Spain in | By the end of the 18th century, Spanish and Portuguese power waned as other European powers took their place, notably Britain and France. Resentment grew over the restrictions imposed by the Spanish government, as well as the dominance of native Spaniards (Iberian-born ''peninsulares'') over the major [[institution]]s and the majority population, including the Spanish descended [[Spanish Criollo peoples|Creole]]s (''criollos''). [[Napoleon I of France|Napoleon]]'s invasion of Spain in 1808 marked the turning point, compelling Creole elites to form juntas that advocated independence. Also, the newly independent [[Haiti]], the second oldest nation in the [[New World]] after the [[United States]], further fueled the independence movement by inspiring the leaders of the movement, such as [[Simón Bolívar]] and [[José de San Martin]], and by providing them with considerable munitions and troops. Fighting soon broke out between the ''Juntas'' and the Spanish authorities, with initial Creole victories, such as Father [[Miguel Hidalgo]]'s in [[Mexico]] and [[Francisco de Miranda]]'s in [[Venezuela]], crushed by Spanish troops. Under the leadership of [[Simón Bolívar]], [[José de San Martin]] and other ''[[Libertadores]]'' the independence movement regained strength, and by 1825, all of Spanish Latin America, except for Puerto Rico and Cuba, gained independence from Spain. [[Brazil]] achieved independence with a constitutional monarchy established in 1822. During the same year in [[Mexico]], a Spanish military officer, [[Agustín de Iturbide]], led conservatives who created a constitutional [[monarchy]], with Iturbide as [[emperor]] (shortly followed by a republic). | ||

==Political divisions== | ==Political divisions== | ||

Revision as of 06:47, 9 June 2009

Latin America

| Area | 21,069,501 sq km |

|---|---|

| Population | 548,500,000 |

| Countries | 22 |

| Dependencies | 7 |

| GDP | $2.26 Trillion (exchange rate) $4.5 Trillion (purchasing power parity) |

| Languages | Spanish, Portuguese, French, Quechua, Aymara, Nahuatl, Mayan languages, Guaraní, Italian, English, German, Welsh, Dutch, Haitian Creole, many others |

| Time Zones | UTC -3:00 (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay) to UTC -8:00 (Mexico) |

| Largest Cities | Mexico City São Paulo Buenos Aires Rio de Janeiro Lima Bogotá Santiago Caracas |

Latin America is the region of the Americas that shares a common tradition and historical heritage of European colonization, mostly Iberian. Geographically, it extends from Mexico in the North to Chile in the extreme South.

Definition

Regarding the popular use of the term Latin America, a strict linguistic perspective suggests that it would include only the countries and territories where Romance languages — Spanish, Portuguese, French, and their creoles - are officially or predominantly spoken. In this view, the English-speaking countries of the Central America and the Caribbean (such as Belize and Jamaica) would not be considered as parts of Latin America, and neither would the former Dutch colonies Suriname, Netherlands Antilles and Aruba, even though the predominantly Iberian influenced language Papiamentu is more widely spoken in the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba than Dutch. Moreover, territories where other Romance languages such as French (e.g., Quebec in Canada) or Kreyol (e.g. Haiti, Martinique and Guadeloupe) predominate are often not reckoned as parts of Latin America in this view, despite the French origins of the concept.

Scholars, however, criticize this perspective on several grounds. First, it overemphasizes the linguistic criterium, at the same time it dismisses the importance of Native American languages (such as Quéchua and Mayan languages), spoken by a large percentage of Latin American population. Second, it underestimates the influence of the cultural heritage and history common to the region. For instance, Jamaica and Haiti share with Cuba and Domenican Republic a history of slavery and plantations, despite the linguistic differences.

To overcome the gap between academic and linguistic definitions for Latin America, some suggest the use of the composed term Latin America and the Caribbean.

Geopolitically, Latin America is divided into 22 independent countries and several dependent territories.

Etymology

Originally a political term, Amerique Latine was coined by French emperor Napoleon III, who cited Amerique Latine and Indochine as goals for expansion during his reign. While the term helped him stake a claim to those territories, it eventually came to embody those parts of the Americas that speak Romance languages initially brought by settlers from Spain, Portugal and, in a minor extent, France in the 15th and 16th centuries. An alternate etymology points to Michel Chevalier, who mentioned the term in 1836. [1]

In the United States, the term was not used until the 1890s, and did not become a common descriptor of the region until early in the twentieth century. Before then, Spanish America was more commonly used. [2]

The term Latin America has come to represent an expression equivalent to Latin Europe and implies a sense of supranationality greater than those implied by notions of statehood or nationhood. This supranational identity is expressed through common initiatives and organizations, like the South American Community of Nations. It is important to observe that the terms Latin American, Latin, Latino, and Hispanic differ from each other.

Many people in Latin America do not speak Latin-derived languages, but native ones or languages brought over by immigration. There is also the blend of Latin-derived cultures with indigenous and African ones resulting in a differentiation in relation to the Latin-derived cultures of Europe.

Quebec, other French-speaking areas in Canada and the United States like Acadia, Louisiana, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, and other places north of Mexico are traditionally excluded from the sociopolitical definition of Latin America, despite having significant populations that speak a Latin-derived language, due in part to these territories' not existing as sovereign states or being geographically separated from the rest of Latin America. French Guiana, however, is often included, despite being a dependency of France and not an independent country.

As alluded to above, the term Ibero-America is sometimes used to refer to the nations that were formerly colonies of Spain and Portugal, as these two countries are located on the Iberian peninsula. The Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI) takes this definition a step further, by including Spain and Portugal (often termed the Mother Countries of Latin America) among its member states, in addition to their Spanish and Portuguese-speaking former colonies in America.

History

- See also: History of South America for a treatment of Pre-Columbian civilisations and a general overview of the region's history.

The Americas are thought to have been first inhabited by people crossing the Bering Land Bridge, now the Bering strait, from northeast Asia into Alaska more than 10,000 years ago. Over the course of millennia, people spread to all parts of the continent. By the first millennium AD/CE, South America’s vast rainforests, mountains, plains and coasts were the home of tens of millions of people. Some groups formed permanent settlements, such as the Chibchas (or "Muiscas" or "Muyscas") and the Tairona groups. The Chibchas of Colombia, the Quechuas of Peru and the Aymaras of Bolivia were the three Indian groups that settled most permanently.

The region was home to many indigenous peoples and advanced civilizations, including the Aztecs, Toltecs, Caribs, Tupi, Maya, and Inca. The golden age of the Maya began about 250, with the last two great civilizations, the Aztecs and Incas, emerging into prominence later on in the early 14th century and mid-15th centuries, respectively.

With the arrival of the Europeans following Christopher Columbus's voyages, the indigenous elites, such as the Incans and Aztecs, lost power to the Europeans. Hernán Cortés destroyed the Aztec elite's power with the help of local groups who disliked the Aztec elite, and Francisco Pizarro eliminated the Incan rule in Western South America. European powers, most notably Spain and Portugal, colonized the region, which along with the rest of the uncolonized world was divided into areas of Spanish and Portuguese control by the Line of Demarcation in 1493, which gave Spain all areas to the west, and Portugal all areas to the east (the Portuguese lands in America subsequently becoming Brazil). By the end of the 16th century, Europeans occupied large areas of Central and South America, extending all the way into the present southern United States. European culture and government was imposed, with the Roman Catholic Church becoming a major economic and political power, as well as the official religion of the region.

Diseases brought by the Europeans, such as smallpox and measles, wiped out a large proportion of the indigenous population, with epidemics of diseases reducing them sharply from their prior populations. Historians cannot determine the number of natives who died due to European diseases, but some put the figures as high as 85% and as low as 20%. Due to the lack of written records, specific numbers are hard to verify. Many of the survivors were forced to work in European plantations and mines. Intermarriage between the indigenous peoples and the European colonists was very common, and, by the end of the colonial period, people of mixed ancestry (mestizos) formed majorities in several colonies.

By the end of the 18th century, Spanish and Portuguese power waned as other European powers took their place, notably Britain and France. Resentment grew over the restrictions imposed by the Spanish government, as well as the dominance of native Spaniards (Iberian-born peninsulares) over the major institutions and the majority population, including the Spanish descended Creoles (criollos). Napoleon's invasion of Spain in 1808 marked the turning point, compelling Creole elites to form juntas that advocated independence. Also, the newly independent Haiti, the second oldest nation in the New World after the United States, further fueled the independence movement by inspiring the leaders of the movement, such as Simón Bolívar and José de San Martin, and by providing them with considerable munitions and troops. Fighting soon broke out between the Juntas and the Spanish authorities, with initial Creole victories, such as Father Miguel Hidalgo's in Mexico and Francisco de Miranda's in Venezuela, crushed by Spanish troops. Under the leadership of Simón Bolívar, José de San Martin and other Libertadores the independence movement regained strength, and by 1825, all of Spanish Latin America, except for Puerto Rico and Cuba, gained independence from Spain. Brazil achieved independence with a constitutional monarchy established in 1822. During the same year in Mexico, a Spanish military officer, Agustín de Iturbide, led conservatives who created a constitutional monarchy, with Iturbide as emperor (shortly followed by a republic).

Political divisions

Latin America is often seen as encompassing the following regions:

| Countries | French Dependencies | United States Dependency | |

|---|---|---|---|

Population

The population of Latin America is an amalgam of ethnic groups. The composition varies from country to country; some have a predominance of a racially mixed population, some have a high percentage of people of Amerindian origin, some are dominated by inhabitants of European origin and some populations are primarily of African origin.

Demographics

Although, many from outside of Latin America may perceive all Latin Americans as being of mixed stock and heritage, Latin America has a very diverse population, with many ethnic groups and different ancestries or races, the majority of which are either of European, African, or Amerindian descent, or a mix of these.

Only in three countries do the Amerindians make up the majority of the population. This is the case of Peru, Guatemala, and Bolivia. In the rest of the Continent, most of the Native American descendants are of partial mixed race ancestry.

Since the 16th century a large number of Iberian colonists left for Latin America: the Portuguese to Brazil and the Spaniards to the rest of the region. An intensive race mixing between the Europeans and the Amerindians occurred (mostly in, and after, the 1800s) and their descendants (known as mestizos) make up the majority of the population in several Latin American countries, such as Mexico, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and Venezuela.

Starting in the late 16th century, a large number of African slaves was brought to Latin America, the majority of whom were sent to the Caribbean and Brazil. Nowadays, Blacks make up the majority of the population in most Caribbean countries. Many of the African slaves in Latin America mixed with the Europeans and their descendants, known as Mulattoes, make up the majority of the population in some countries, such as Cuba, and large percentages in Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, and Belize. Mixes between the Blacks and Amerindians also occurred, and their descendants are known as Zambos. Many Latin American countries also have a substantial tri-racial population, which ancestry is a mix of Amerindian, White, and Black, especially in Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Brazil, and the Dominican Republic.

Large numbers of European immigrants arrived in Latin America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most of them settling in the Southern Cone (Argentina, Chile, Uruguay) and in southern Brazil. Nowadays this combined region has a large majority of people of European descent and in all more than two thirds of Latin America's white population, which is in turn more than 90% composed of descendants of the top five groups of immigrants, which were: Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese, Germans and Irish. Some of the other groups are Poles, Russians, Welsh, Ukrainians, French, Croatians and Jews.

In this same period, many immigrants came from the Middle-East and Asia, including Indians, Lebanese, Syrians, and, more recently, Koreans, Chinese and Japanese (mainly in Brazil). In the late 19th century, a small wave of Americans, mostly from the former Confederate States or the Southern U.S. settled in Brazil and fewer across Latin America.

This genetic diversity has profoundly influenced religion, music, and politics, and gave rise to a weak feeling of identity in parts of these mixed cultures. This opaque cultural heritage is (arguably improperly) called Latin or Latino in United States' English. Outside of the U.S., and in many languages (especially romance ones) "Latino" just means "Latin", referring to cultures and peoples that can trace their heritage back to the ancient Roman Empire. Latin American is the proper term.

Ethnic Origin

These figures include 19 of the 20 Latin American nations. Venezuela is not included as it does not include race on its census.

Total Population 522.8 million.

Racial groups: 174 million White (33.3% of the total population), 133.8 million Mestizo (25.6%), 90.3 million Mulatto (17.3%), 60.8 million Amerindian or Native Peoples (11.6%), 31.5 million White/Mestizo (6%; a few countries count Whites and Mestizos together), 24.8 million Black (4.7%), 1.4 Asian (0.3%; this figure may be much lower than the actual one), 6.2 million Other and Unknown (1.2%). As these numbers show, although almost every Latin American country has a majority population, that is not the case for the region as a whole. [Note: Venezuela's population is 26,749,000. Applying to this the country's 1998 race ratios (mestizo 67%, white 21%, black 10%, Amerindian 2% [1]) yields, for the entire region: Population 549,549,000; White 32.7%, Mestizo 27.6%, Mulatto 16.4%, Amerindian or Native Peoples 11.2%, White/Mestizo 5.7%, Black 5%, Asian 0.3%, Other and Unknown 1.1%].

Language

Spanish is the predominant language in the majority of the countries. Portuguese is spoken primarily in Brazil, where it is both the official and the national language. French is also spoken in smaller countries, in the Caribbean, and in French Guiana. Dutch is the official language on various Caribbean islands and in Suriname on the continent. English is the official language of Belize, Barbados, Jamaica, and the US Virgin Islands.

- See also: Amerindian languages

Several nations, especially in the Caribbean, have their own Creole languages, derived from European languages and various African tongues. Native American languages are spoken in many Latin American nations, mainly Peru, Ecuador, Guatemala, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Mexico. Nahuatl is only one of the 62 native languages spoken by indigenous people in Mexico, which are officially recognised by the government as "national languages", along with Spanish. Guarani is, along with Spanish, the official language of Paraguay, and is spoken by a majority of the population.

Other European languages spoken include Italian in Brazil and Argentina, German in southern Brazil, southern Chile and Argentina, and Welsh in southern Argentina.

Religion

The primary religion throughout Latin America is Roman Catholicism. Latin America, particularly Brazil, is active in developing the quasi-socialist Roman Catholic movement known as Liberation Theology. Practitioners of the Protestant, Pentecostal, Evangelical, Mormon, Buddhist, Jewish, Islamic, Hindu, Bahá'í, and indigenous denominations and religions exist. Various Afro-Latin American traditions, such as Santería, and Macumba, a tribal- voodoo religion are also practiced. Evangelicalism in particular is increasing in popularity. [3]

Economy

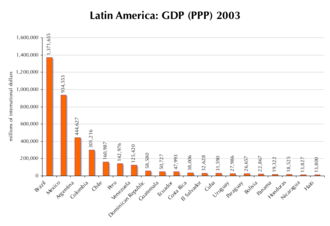

Template:Expandsection Below is a table showing the Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) prices and the GDP (PPP) of each Latin American country. This can be used to roughly gauge the standards of living in the region. Data compiled from the year 2005. The Latin American G7 is composed of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela. Income equality data --according to Gini index (the higher the number, the higher the inequality) -- is based on List of countries by income equality, survey year of data varies.

| Country | GDP (PPP) per capita | GDP (PPP) | Income equality |

|---|---|---|---|

| international dollars | millions of international dollars | Gini index | |

| Template:ARG | 14,109 | 533,722 | 52.2 |

| Template:CHI | 11,937 | 193,213 | 57.1 |

| Template:CRC | 10,434 | 45,137 | 46.5 |

| Template:MEX | 10,186 | 1,072,563 | 54.6 |

| Template:URU | 10,028 | 34,305 | 44.6 |

| Template:BRA | 8,584 | 1,576,728 | 59.3 |

| Template:COL | 7,565 | 337,286 | 57.6 |

| Template:PAN | 7,283 | 23,495 | 56.4 |

| Template:DOM | 7,203 | 65,042 | 47.4 |

| Template:VEN | 6,186 | 163,503 | 49.1 |

| Template:PER | 5,983 | 167,747 | 49.8 |

| Template:PAR | 4,555 | 28,342 | 57.8 |

| Template:SLV | 4,511 | 31,078 | 53.2 |

| Template:ECU | 4,316 | 57,039 | 43.7 |

| Template:GUA | 4,155 | 57,000 | 59.9 |

| Template:NIC | 3,636 | 20,996 | 43.1 |

| Template:HON | 3,009 | 21,740 | 55 |

| Template:CUB | 3,000 | 33,920 | unknown |

| Template:BOL | 2,817 | 25,648 | 44.7 |

| Template:HAI | 1,783 | 14,917 | unknown |

| Latin America | 8,105 | 4,421,569 |

Sources: Data from table are from an April 2005 report by the IMF and graphics data are from data by the World Bank from 2003 [2]. Data for Cuba is a 2004 estimate from the CIA World Factbook. GDP (PPP) per capita for Latin America was calculated using population data from List of countries by population

Cultural diversity

The rich mosaic of Latin American cultural expressions is the product of many diverse influences, derived mainly from :

- Native cultures of the peoples that inhabited the continents prior to the arrival of the Europeans.

- European cultures, brought mainly by the Spanish, the Portuguese and the French. This can be seen in any expression of the region's rich artistic traditions, including painting, literature and music, and in the realms of science and politics. The most enduring European colonial influence was language. Italian and British influence has been important as well.

- African cultures, who were part of a long history of New World slavery. Peoples of African descent have influenced the ethno-scapes of Latin America and the Caribbean. This is manifest in the Caribbean through dances such as the bomba, the plena, the candombe, the cumbia, to mention but a few.

Painting

- See also: Latin American painters

The development of Latin American painting stemmed originally from the styles brought along by Spanish, Portuguese and French Baroque Painters, which in turn were following the trends of the Italian Masters. This Eurocentrism of the Arts, in general, started to fade in the early 20th century, as Latin-Americans began to acknowledge the uniqueness of their condition and started to follow their own path.

From the early 20th century, the art of Latin America was greatly inspired by the Constructivist Movement. The Constructivist Movement was founded in Russia around 1915 by Vladimir Tatlin. The Movement quickly spread from Russia to Europe and then into Latin America. Joaquin Torres Garcia and Manuel Rendón have been credited with bringing the Constructivist Movement into Latin America from Europe.

Another important artistic movement generated in Latin America is Mexico's Muralismo represented by the world famous painters Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco and Rufino Tamayo. Some of the most impressive Muralista works can be found in Mexico, New York, Los Angeles and Philadelphia.

Mexican painter Frida Kahlo remains by far the most known and famous Latin American artist. She painted about her own life and the Mexican culture in a style combining Realism, Symbolism and Surrealism. Kahlo's work holds the highest selling price of all Latin American paintings.

Literature

Latin American literature gained its own identity, evolving from the strong European and, at a later stage, Anglo-American influences, and is very recognisable internationally, including renowned Nobel Prize winners such as the Colombian Gabriel García Márquez (One Hundred Years of Solitude) and the Mexican Octavio Paz (The Labyrinth of Solitude). Others include João Guimarães Rosa in Brazil, with his book "Grande Sertão - Veredas", and older writers such as Machado de Assis and ( "Dom Casmurro" ).

Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda (in 1971) are known Chilean Nobel Prize winners. The Argentine Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) is a solid and influential figure of Latin-American letters. [4]

Other important Latin-American writers are:

Music

One of the main characteristics of Latin American music is its diversity, from the lively rhythms of Central America and the Caribbean to the more austere sounds of southern South America. Another feature of Latin American music is its original blending of the variety of styles that arrived in The Americas and became influential, from the early Spanish and European Baroque to the different beats of the African rhythms.

Hispano-Caribbean music, such as salsa, merengue, bachata, etc. from Panama, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, are styles of music that have been strongly influenced by African rhythms and melodies. [5] [6]

Other main musical genres of Latin American include the Argentine and Uruguayan tango, the Colombian cumbia and vallenato, Mexican ranchera, Uruguayan Candombe and the various styles of music from Pre-Columbian traditions that are widespread in the Andean region. In Brazil, samba, American jazz, European classical music and choro combined into the bossa nova music. Recently the Haitian kompa has become increasingly popular. [7]

The classical composer Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) worked on the recording of native musical traditions within his homeland of Brazil. The traditions of his homeland heavily influenced his classical works. [8] Also notable is the recent work of the Cuban Leo Brouwer and guitar work of the Venezuelan Antonio Lauro and the Paraguayan Agustín Barrios.

Arguably, the main contribution to music entered through folklore, where the true soul of the Latin American and Caribbean countries is expressed. Musicians such as Atahualpa Yupanqui, Violeta Parra, Victor Jara, Mercedes Sosa, Jorge Negrete, Caetano Veloso, and others gave magnificent examples of the heights that this soul can reach.

Latin pop, including many forms of rock, is popular in Latin America today (see Spanish language rock and roll). [9]

More recently, Reggaeton, a blend of Latin rhythms with Hip hop music which originated in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Panama, and Cuba is becoming more popular, in spite of the controversy surrounding its lyrics, dance steps and music videos. It has become very popular among Hispanic populations in the U.S. particularly in southern Florida as well as in the Hispanic populations in New York City. This has produced a trickling affect across the Hispanic populations across the U.S. with many reggaeton radio stations opening up in U.S. cities with large percentages of Hispanics such as in Phoenix, AZ, Denver, Co, Houston, Tx, as well as multiple reggaeton stations in southern California.

Film

Latin American film is both rich and diverse. The 1950s and 1960s saw a movement towards Third Cinema, led by the Argentine filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino.

Mexican movies from the Golden Era in the 1940s are the greatest examples of Latin American cinema, with a huge industry comparable to the Hollywood of those years. Mexican movies were exported and exhibited in all Latin America. More recently movies such as Amores Perros (2000), Y tu mamá también (2001) and Babel (2005) have been successful in creating universal stories about contemporary subjects, and were internationally recognised, as in the prestigious Cannes Film Festival. Mexican directors Alejandro González Iñárritu, Alfonso Cuarón (Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban) and screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga are some of the most known present-day film makers.

Argentine cinema was a big industry in the first half of the 20th century. After a series of military governments that shackled culture in general, the industry re-emerged after the 1976–1983 military dictatorship to produce the Academy Award winner The Official Story in 1985. The Argentine economic crisis affected the production of films in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but many Argentine movies produced during those years were internationally acclaimed, including Nueve reinas (2000), El abrazo partido (2004) and Roma (2004).

In Brazil, the Cinema Novo movement created a particular way of making movies with critical and intellectual screenplays, a clearer photography related to the light of the outdoors in a tropical landscape, and a political message. The modern Brazilian film industry has become more profitable inside the country, and some of its productions have received prizes and recognition in Europe and the United States. Movies like Central do Brasil (1999) and Cidade de Deus (2003) have fans around the world, and its directors have taken part in American and European film projects.

Notes

- ↑ In his Lettres sur l'Amèrique du Nord

- ↑ Latin American (Last accessed 07-15-06).

- ↑ Paul Sigmund (Last accessed 05-21-06). Education and Religious Freedom in Latin America. Princeton University.

- ↑ Calin-Andrei Mihailescu (Last accessed 05-21-06). This Craft of Verse. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Dr. Christopher Washburne (Last accessed 05-23-06). Clave: The African Roots of Salsa. University of Salsa.

- ↑ Guide to Latin Music. Caravan Music (Last accessed 05-23-06).

- ↑ Daddy Yankee leads the reggaeton charge, Associated Press, Last accessed 05-23-06.

- ↑ Heitor Villa-Lobos. Leadership Medica (Last accessed 05-23-06).

- ↑ The Baltimore Sun. Latin music returns to America with wave of new pop starlets, The Michigan Daily, Last accessed 05-23-06.