Tennessee River: Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{dambigbox|Tennessee River|Tennessee}} | {{dambigbox|Tennessee River|Tennessee}} | ||

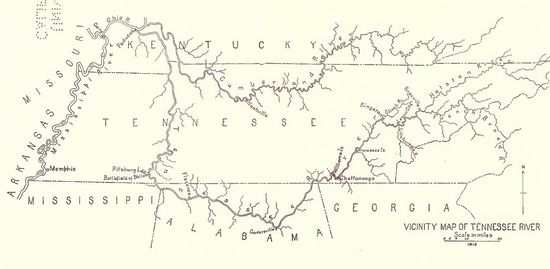

{{Image|TENN river.jpg|left| | {{Image|TENN river.jpg|left|550px|The Tennessee river and its tributaries in 1915, before any part was dammed.<ref>From the book "Aboriginal Sites on Tennessee River" by Clarence B. Moore, reprinted from the Journal of The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia Vol. XVI, 1915. This view is from a screen shot from the PDF file, rotated and cropped. </ref>}} | ||

The '''Tennessee River''' is the [[Ohio River]]'s largest tributary. Slicing twice through [[Tennessee (U.S. state)|Tennessee]], and passing through both [[Alabama (U.S. state)]] and [[Kentucky (U.S. state)|Kentucky]], the Tennessee river was 652 miles long in 1915, before any portions of it were dammed. Since the 1930's, the [[Tennessee Valley Authority]] (TVA) dammed the Tennessee and its tributaries in several places, vastly altering the flow of water and the ecology of the river valley. | The '''Tennessee River''' is the [[Ohio River]]'s largest tributary. Slicing twice through [[Tennessee (U.S. state)|Tennessee]], and passing through both [[Alabama (U.S. state)]] and [[Kentucky (U.S. state)|Kentucky]], the Tennessee river was 652 miles long in 1915, before any portions of it were dammed. Since the 1930's, the [[Tennessee Valley Authority]] (TVA) dammed the Tennessee and its tributaries in several places, vastly altering the flow of water and the ecology of the river valley. | ||

Revision as of 21:35, 6 August 2023

The Tennessee River is the Ohio River's largest tributary. Slicing twice through Tennessee, and passing through both Alabama (U.S. state) and Kentucky, the Tennessee river was 652 miles long in 1915, before any portions of it were dammed. Since the 1930's, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) dammed the Tennessee and its tributaries in several places, vastly altering the flow of water and the ecology of the river valley.

The river's upper half flows southward, and its lower half northward. The Tennessee river begins in East Tennessee a short distance above the city of Knoxville. It is formed by the junction of the French Broad and the Holston rivers. From the conjunction of those two rivers, the Tennessee river flows southwest until, south of and below the city of Chattanooga, it enters the state of Alabama.

In Alabama, the Tennessee river flows first southwest and then northwest past the Muscles Shoals (near Florence, AL), a shallow and unnavigable rapids, and the only unnavigable portion of the river. After the shoals, the river soon runs along the northeast corner of the state of Mississippi for about ten miles its western side. Then the river again enters the state of Tennessee, now flowing northward. It divides Middle Tennessee from West Tennessee. After passing through Tennessee, the river enters Kentucky and after 40 to 50 miles it flows into the Ohio river at Paducah.

Dams

Since the 1930's, the Tennessee itself has been dammed nine times. Those dams are shown here in their order along the river from its source to where it flows into the Ohio River:

- Fort Loudoun Dam, which created Fort Loudoun Lake near Knoxville, Tennessee

- Watts Bar Dam, which created Watts Bar Lake

- Chickamauga Dam, which created Chickamauga Lake

- Nickajack Dam, which created Nickajack Lake

- Guntersville Dam, which created Guntersville Lake

- Wheeler Dam, which created Wheeler Lake

- Wilson Dam, which created Wilson Lake

- Pickwick Landing Dam, which created Pickwick Lake near the meeting point of the Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee borders, just south of Savannah, Tennessee

- Kentucky Dam, which created Kentucky Lake near Paducah, Kentucky, built in the 1930's

In addition, the river's dozens of tributaries have also been dammed in nearly two dozen places. The original goals of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), created under Roosevelt during the Great Depression of the 1930's, was threefold: 1) to provide jobs, 2) to generate low-cost hydro-electric power, and 3) to contribute to flood control of the Mississippi River basin. While these goals were accomplished, a significant amount of environmental destruction (and other side effects) eventually caused the public, by the 1970's, to resist the building of any more dams than already exist.

The watershed

Notes

- ↑ From the book "Aboriginal Sites on Tennessee River" by Clarence B. Moore, reprinted from the Journal of The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia Vol. XVI, 1915. This view is from a screen shot from the PDF file, rotated and cropped.