Ulysses S. Grant: Difference between revisions

imported>Pat Palmer (linking to Vicksburg) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

{{succession box| | {{succession box| | ||

before=[[Andrew Johnson]]| | before=[[Andrew Johnson]]| | ||

title=[[President of the United States]]| | title=[[President of the United States of America]]| | ||

years=1869-1877| | years=1869-1877| | ||

after=[[Rutherford Hayes]] | after=[[Rutherford Hayes]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{end box}} | {{end box}} | ||

[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 17:00, 2 November 2024

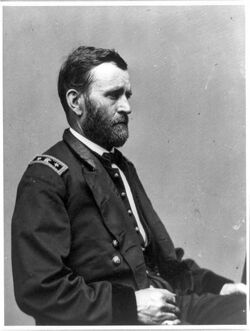

Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885) American general and 18th president of the United States (1869-1877) won fame for his capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi (1863) and defeat of Robert E. Lee (1865), thereby winning the American Civil War. He is commemorated on the U.S. $50 bill.

Early career

Grant was born April 27, 1822, in a two-room cabin at Point Pleasant, Ohio. His father, Jesse Root Grant, was descended from undistinguished Puritan forebears who had immigrated to Massachusetts in the early 17th century. His mother, Hannah Simpson Grant, was a typical hard-working and pious frontier woman. The elder Grant was a tanner who by hard work and native shrewdness managed to acquire a modest competence. Lacking much education himself, he was determined that his sons should have the best the community offered. From the time he was 6 until he was nearly 17, young Grant regularly attended school, first in Georgetown, Ohio, to which the family had moved soon after he was born, and later at nearby academies. While working on the family, he developed a fondness for horses almost amounting to a passion, and a liking for outdoor life that in after years stood him in good stead.

In 1839, his father obtained for him an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. In making out the necessary papers, the congressman erroneously wrote his name as Ulysses Simpson Grant (Simpson was his mother's name) instead of Hiram Ulysses Grant, the name with which he had been christened. His name was so entered on the rolls of the Military Academy. Grant never liked his old initials H.U.G. and took the new mane. Except for his horsemanship Grant did not distinguish himself at West Point, which had an engineering curriculum. Graduating in 1843, twenty-first in a class of thirty-nine, he was sent to the infantry instead of to the cavalry, his choice. He served at various posts in Missouri and Louisiana, but in 1845 he was ordered to accompany General Zachary Taylor to Texas and later served in the invasion of Mexico. Subsequently he was transferred to General Winfield Scott's army in time to participate in the march on Mexico City. Grant handled logistics, and did not have a combat role, but he was twice cited for gallantry under fire. He was an unusually keen observer of terrain, battle formations, and the actions of commanders, and by happenstance was involved in most of the major battles of the war. In later years he said it was an unjust war, but he did not say that at the time.

Stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, after the Mexican War, in August 1848 he married Julia Dent, daughter of a Missouri planter and slaveowner. Four years later, now a captain, Grant was transferred to the Fort Humboldt, in far northern California; his wife could not accompany him because of the hardships of the trip. Unhappy because of the loneliness and enforced separation, Grant, still a first lieutenant, started drinking. "I do nothing here but set in my room and read and occasionally take a short ride on one of the public horses," he wrote his wife. His commander, Lt Col Col. Robert C. Buchanan Buchanan, hated him and forced him to resign.[1] The six years that followed were the most disappointing of his life. He tried farming on land in the St. Louis area owned by his wife's father. He failed at that, at selling real estate, and at clerking in a customs house. He owned one slave. In financial straits, he finally turned to his own family and became a clerk in a Galena, Illinois, leather store owned by his two brothers.

Civil War in the West

Civil War in the East

Washington Politics 1865-68

Presidency: First Term 1868-72

Presidency: Second Term 1872-76

Retirement

His death and funeral became an occasion for a religiously tinged emotional and political reconciliation of North and South and as such is a critical event in the history of the political culture of the United States. "I am sorry General Grant is dead," proclaimed ex-Confederate general and pallbearer Simon Bolivar Buckner, "but his death has yet been the greatest blessing the country has ever received, now, reunion is perfect."[2]

Legacy

Throughout the 20th century Grant was considered one of the two or three worst presidents, because of the corruption he tolerated, his misplaced loyalty to old comrades, his disdain for good government and rejection of good advice, his Reconstruction policies that favored the Republican party at the expense of the republican principles on which the party was founded, and the economic disaster that struck the nation in the panic of 1873, making his second term a period of hardship.

In recent years Grant's reputation as president has improved somewhat. Smith (2002)[3] is typical in that it acknowledges Grant's flaws, but portrays him as a man of character and as the ultimate pragmatist, a man whose virtues and achievements far outweighed the faults and scandals often associated with his career.

Grant's military reputation stands very high indeed, except in the one area of moral judgment, whether he sacrificed thousands of lives in a meat grinder war of attrition. Smith (2002) highlights the pragmatic Grant, willing to violate the orthodoxies of military strategy as he learned what the battlefield taught and forgot what the old textbooks said. For Grant warfare was an end in itself, a kind of brutal game among rival commanders. Smith (2002) wants to challenge what he sees as a common historical image of Grant as a general whose victories may be attributed to a simple willingness to sacrifice troops in battle, but he still presents a Grant remarkably willing to sacrifice troops in a conflict he defined as, ultimately, a war of attrition.

Bibliography

Biography

- Bunting III, Josiah. Ulysses S. Grant (2004), 208pp ISBN 0-8050-6949-6 excerpt and text search

- Garland, Hamlin. Ulysses S. Grant: His Life and Character, (1898), 524pp full text online

- Korda, Michael. Ulysses S. Grant: The Unlikely Hero (2004) 161 pp

- Longacre, Edward G. Ulysses S. Grant: The Soldier And the Man (2006) excerpt and text search

- McFeely, William S. Grant: A Biography, (1981), ISBN 0-393-01372-3, Pulitzer prize, but negative twoard Grant. excerpt and text search

- Mosier, John., "Grant", (2006), 224pp; ISBN 1-4039-7136-6. excerpt and text search

- Simpson, Brooks D. Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822-1865, (2000), ISBN 0-395-65994-9. first volume of major scholarly biography excerpt and text search

- Smith, Jean Edward, Grant, (2002), 781pp; ISBN 0-684-84927-5. excerpt and text search

Historiography

- Rafuse, Ethan S. "Still a Mystery? General Grant and the Historians, 1981-2006," The Journal of Military History 71 #3 (July 2007): 849-874. in Project Muse

- Waugh, Joan. "U.S. Grant, Historian," in The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture, ed, by Alice Fahs and Joan Waugh (2004), 5-38, on writing the memoirs

- Wilson, Edmund. Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War (1962) pp 131-73, on the Memoirs

Military

- Badeau, Adam. Military History of Ulysses S. Grant, from April, 1861, to April, 1865. 3 vols. 1882. full text online

- Catton, Bruce, U. S. Grant and the American Military Tradition (1954)

- Conger, A. L. The Rise of U.S. Grant (1931) online edition

- Lewis, Lloyd. Captain Sam Grant (1950), ISBN 0-316-52348-8, Mexican War

- Williams, Kenneth P. Lincoln Finds a General: A Military Study of the Civil War (5 vol 1959)

- Williams, T. Harry, McClellan, Sherman and Grant. 1962.

Western front: 1861-1863

- Ballard, Michael B., Vicksburg, The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi, (2004), ISBN 0-8078-2893-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C., The Vicksburg Campaign, 3 volumes, 1991, ISBN 0-89029-308-2.

- Carter, Samuel III, The Final Fortress: The Campaign for Vicksburg, 1862-1863 (1980)

- Catton, Bruce, Grant Moves South, 1960, ISBN 0-316-13207-1; * Gott, Kendall D., Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862, 2003, ISBN 0-8117-0049-6.

- McDonough, James Lee, Shiloh: In Hell before Night (1977).

- McDonough, James Lee, Chattanooga: A Death Grip on the Confederacy (1984).

- Martin, David G. The Vicksburg Campaign: April 1862-July 1863 (1994) excerpt and text search

- Miers, Earl Schenck., The Web of Victory: Grant at Vicksburg. 1955.

Eastern front: 1864-65

- Catton, Bruce. Grant Takes Command (1968)

- Cavanaugh, Michael A., and William Marvel, The Petersburg Campaign: The Battle of the Crater: "The Horrid Pit," June 25-August 6, 1864 (1989)

- Davis, William C. Death in the Trenches: Grant at Petersburg (1986).

- Fuller, Maj. Gen. J. F. C., Grant and Lee, A Study in Personality and Generalship,

- Gallagher, Gary W. ed. The Wilderness Campaign (1997) excerpt and text search

- McWhiney, Grady, Battle in the Wilderness: Grant Meets Lee (1995)

- Maney, R. Wayne, Marching to Cold Harbor. Victory and Failure, 1864 (1994).

- Matter, William D., If It Takes All Summer: The Battle of Spotsylvania (1988) excerpt and text search

- Miller, J. Michael, The North Anna Campaign: "Even to Hell Itself," May 21-26, 1864 (1989).

- Rhea, Gordon C., The Battle of the Wilderness May 5–6, 1864, (1994) ISBN 0-8071-1873-7. excerpt and text search

- Rhea, Gordon C., The Battles for Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern May 7–12, 1864, (1997), ISBN 0-8071-2136-3. excerpt and text search

- Rhea, Gordon C., To the North Anna River: Grant and Lee, May 13–25, 1864, (2000), ISBN 0-8071-2535-0. excerpt and text search

- Rhea, Gordon C., Cold Harbor: Grant and Lee, May 26 – June 3, 1864, (2002), ISBN 0-8071-2803-1. [ excerpt and text search]

- Simpson, Brooks D, "Continuous Hammering and Mere Attrition: Lost Cause Critics and the Military Reputation of Ulysses S. Grant," in Gary Gallagher and Alan T. Nolan, eds., The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History, (2000)

- Trudeau, Noah. Bloody Roads South: The Wilderness to Cold Harbor, May-June 1864 (2002) excerpt and text search

Politics

- Hesseltine, William B. Ulysses S. Grant, Politician (2001) ISBN 1-931313-85-7 online edition

- Mantell, Martin E. Johnson, Grant, and the Politics of Reconstruction (1973) online edition

- Nevins, Allan. Hamilton Fish: The Inner History of the Grant Administration (1936) online edition, covers the diplomatic and some political history of his administration

- Rhodes, James Ford., History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896. Volume: 6 and 7 (1920) vol 6

- Scaturro, Frank J. President Grant Reconsidered (1998). excerpt and text search

- Simpson, Brooks D. Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861-1868 (1991). excerpt and text search

- Simpson, Brooks D. The Reconstruction Presidents (1998)

- Skidmore, Max J. "The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant: a Reconsideration." White House Studies (2005) online

Primary sources

- Grant, Ulysses S. Memoirs (1885) online edition

- Grant, Ulysses S. Memoirs and Selected Letters (Mary Drake McFeely & William S. McFeely, eds.) (The Library of America, 1990) ISBN 978-0-94045058-5

- Wilson, Edmund. Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War (1962) pp 131-73, on the Memoirs

- Johnson, R. U., and Buel, C. C., eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. 4 vols. (1887-88); essays by leading generals of both sides; often reprinted; online edition

- Porter, Horace, Campaigning with Grant (1897, reprinted 2000) complete online edition

- Sherman, William Tecumseh, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman. 2 vols. 1875. complete edition online

- Simon, John Y., ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Southern Illinois University Press (1967- ) multivolume complete edition of letters to and from Grant. As of 2007, vol 1-28 covers through September 1878; two more volumes are forthcoming

- vol. 1: 1837-1861 online edition

- vol. 2: April, 1861 - September 1861 online edition

- vol, 3: October 1, 1861 - January 7, 1862 online edition

- vol, 4: January 8 - March 31, 1862 online edition

- vol. 5: April 1 1862 - August 31, 1862 online edition

- vol, 6: September 1, 1862 - December 8, 1862 online edition

- vol, 7: December 9, 1862 - March 31, 1863 online edition

- vol. 8: April 1 1863 - July 6, 1863 online edition

- vol, 9: July 7 1863 - December 31, 1863 online edition

- vol. 10: January 1 - May 31, 1864 online edition

Notes

- ↑ There was no disgrace involved. In the 1860s Buchanan was repeatedly challenged on why he forced out the greatest soldier of the era, and came up with the drinking story. Grant drank less than the others at the remote post.

- ↑ Joan Waugh, "'Pageantry of Woe': The Funeral of Ulysses S. Grant." - Civil War History. 51#2 (2005) PP 151+ online edition.

- ↑ Jean Edward Smith, Grant (2002)