Prime number/Citable Version: Difference between revisions

imported>Greg Woodhouse (adding brief statements of twin prime and Golbach conjectures) |

imported>Jitse Niesen m (→The Golbach Conjecture: spelling) |

||

| Line 157: | Line 157: | ||

'''Twin primes''' are pairs of prime numbers differing by 2. Examples of twin primes include 5 and 7, 11 and 13, and 41 and 43. It is unknown whether there are infinitely many such pairs. | '''Twin primes''' are pairs of prime numbers differing by 2. Examples of twin primes include 5 and 7, 11 and 13, and 41 and 43. It is unknown whether there are infinitely many such pairs. | ||

===The | ===The Goldbach Conjecture=== | ||

The ''' | The '''Goldbach conjecture''' is that every [[even]] number greater than 2 can be expressed as the sum of two primes. | ||

==The Prime Number Theorem== | ==The Prime Number Theorem== | ||

Revision as of 23:06, 8 April 2007

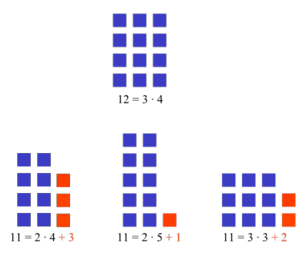

A prime number is a whole number (i.e., one having no fractional or decimal part) that cannot be evenly divided by any numbers but 1 and itself. The first few prime numbers are 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, and 17. With the exception of Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 2} , all prime numbers are odd numbers, but not every odd number is prime. For example, Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 9 = 3\cdot3} and Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 15 = 3\cdot5} , so neither 9 nor 15 is prime. The study of prime numbers has a long history, going back to ancient times, and it remains an active part of number theory (a branch of mathematics) today. It is commonly believed that the study of prime numbers is an interesting, but not terribly useful, area of mathematical research. While this used to be the case, the theory of prime numbers has important applications now. Understanding properties of prime numbers and their generalizations is essential to modern cryptography, and to public key ciphers that are crucial to Internet commerce, wireless networks and, of course, military applications. Less well known is that other computer algorithms also depend on properties of prime numbers.

Definition

Prime numbers are usually defined to be positive integers (other than 1) with the property that they are only (evenly) divisible by 1 and themselves. In other words, a number Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n \in \mathbb{N}} is said to be prime if there are exactly two Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m \in \mathbb{N}} such that Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m | n} , namely Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m = 1} and Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m = n} .

There is another way of defining prime numbers, and that is that a number is prime if whenever it divides the product of two numbers, it must divide one of those numbers. A nonexample (if you will) is that 4 divides 12, but 4 does not divide 2 and 4 does not divide 6 even though 12 is 2 times 6. This means that 4 is not a prime number. We may express this second possible definition in symbols (a phrase commonly used to mean "in mathematical notation") as follows: A number Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p \in \mathbb{N}} is prime if for any Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle a, b \in \mathbb{N}} such that Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p | ab} (read p divides ab), either Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p | a} or Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p | b} . If the first characterization of prime numbers is taken as the definition, the second is derived from it as a theorem, and vice versa.

- Aside on mathematical notation: The second sentence above is a translation of the first into mathematical notation. It may seem difficult at first (perhaps even a form of obfuscation!), but mathematics relies on precise reasoning, and mathematical notation has proved to be a valuable, if not indispensible, aid to the study of mathematics. It is commonly noted while ancient Greek mathematicians had a good understanding of prime numbers, and indeed Euclid was able to show that there are infinitely many prime numbers, the study of prime numbers (and algebra in general) was hampered by the lack of a good notation, and this is one reason ancient Greek mathematics (or mathematicians) excelled in geometry, making comparatively less progress in algebra and number theory.

Unique factorization

Every integer N > 1 can be written in a unique way as a product of prime factors, up to reordering. to see why this is true, assume that N can be written as a product of prime factors in two ways

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N = p_1 p_2 \cdots p_m = q_1 q_2 \cdots q_n}

We may now use a technique known as mathematical induction to show that the two prime decompositions are really the same.

Consider the prime factor Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p_1} . We know that

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p_1 \mid q_1 q_2 \cdots q_n.}

Using the second definition of prime numbers, it follows that Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p_1} divides one of the q-factors, say Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle q_i} . Using the first definition, Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p_1} is in fact equal to Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle q_i}

Now, if we set Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N_1 = N/p_1} , we may write

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N_1 = p_2 p_3 \cdots p_m}

and

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N_1 = q_1 q_2 \cdots \hat{q}_i \cdots q_n}

where the circumflex ("hat symbol") indicates that Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle q_i} is not part of the prime factorization of Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N_1} .

Continuing this way, we obtain a sequence of numbers Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N = N_0 > N_1 > N_2 > \ldots > N_n = 1} where each Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N_{\alpha}} is obtained by dividing Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N_{\alpha - 1}} by a prime factor. In particular, we see that Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle m = n} and that there is some permutation ("rearrangement") σ of the indices Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 1, 2, \ldots n} such that Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p_i = q_{\sigma(i)}} . Said differently, the two factorizations of N must be the same up to a possible rearrangement of terms.

There are infinitely many primes

One basic fact about the prime numbers is that there are infinitely man of them. In other words, the list of prime numbers 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, ... doesn't ever stop. There are a number of ways of showing that this is so, but one of the oldest and most familiar proofs goes back go Euclid.

Euclid's proof

Suppose the set of prime numbers is finite, say Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \{ p_1, p_2, p_3, \ldots, p_n \}} , and let

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N = p_1 p_2 \cdots p_n +1}

then for each Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle i \in 1, \ldots, n} we know that Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle p_i \not| N} (because the remainder is 1). This means that N is not divisible by an prime, which is impossible. This contradiction shows that our assumption that there must only be a finite number of primes must have been wrong and thus proves the theorem.

Euler's proof

The Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler showed how the existence of infinitely many primes could be demonstrated using a rather different approach. The starting point is the fact that the harmonic series

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \ldots + \frac{1}{n} + \ldots}

diverges. That is, for any Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N > 0} , we can choose n such that

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \ldots + \frac{1}{n} > N}

A second fact we will need about infinite series is that if Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |x| > 1}

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle 1 + \frac{1}{x} + \frac{1}{x^2} + \ldots = \frac{1}{1 - \frac{1}{x}}}

Now, unique factorization gives us

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sum_{i = 1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{i} = \prod_p \frac{1}{1 - \frac{1}{p}}}

where the sum on the left is the harmonic series, and the product on the right is extended over all primes p. Now, if there are only finitely many primes, the product on the right has a (finite) value, but the harmonic series (the sum on the left) diverges. This shows that there must be infinitely many primes, after all.

- Remark: One might well wonder what point there is in offering multiple proofs of the same result. After all, isn't one enough? In mathematics, the point of writing a proof is not so much to establish that something is true, but to understand why it is true. Euclid's proof is purely algebraic, and ultimately depends on the fact that prime numbers can be characterized in two different ways. Euler's proof, on the other hand, makes use of a couple of facts about infinite series combined with the unique factorization property establishe above. What is interesting is that these two proofs (and there are many others) use ideas from very different parts of mathematics to arrive at the same result. One has the feeling that this is evidence of particularly deep interconnections between different parts of mathematics.

The Zeta Function

Euler himself introduced the idea of studying the function (of a real variable s)

- Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \zeta(s) = \sum_{n = 1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n^{-s}} = \prod_p \frac{1}{1 - p^{-s}}}

It is not immediately obvious that this even defines a function, but in modern language, the above series converges absolutely if Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle s > 1 + \epsilon} , so the series not only converges, but defines a continuous function.

Locating primes

How can we tell which numbers are prime and which are not? It is sometimes possible to tell that a number is not prime from looking at its digits: for example, any number larger than 2 whose last digit is even is divisble by 2 and hence not prime, and any number ending with 5 is divisible by 5. Therefore, any prime number larger than 5 must end with 1, 3, 7 or 9. This check can be used to rule out the possibility of a randomly chosen number being prime roughly half of the time, but a number that ends with 1, 3, 7 or 9 could have a divisor that is harder to spot.

To find prime numbers, we must use a systematic procedure — an algorithm. Nowadays, prime-finding calculations are performed by computers, often using very complicated algorithms, but there are simple algorithms that can be carried out by hand if the numbers are small. In fact, the simplest methods for locating prime numbers are some of the oldest algorithms, known since antiquity. Two classical algorithms are called trial division and the sieve of Eratosthenes.

Trial division

Trial division consists of systematically searching the list of numbers 2, 3, ..., Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n-1} for a divisor; if none is found, the number is prime. If n has a small divisor, we can quit as soon as we've found it, but in the worst case — if n is prime — we have to test all Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n-2} numbers to be sure. This algorithm can be improved by realizing the following: if n has a divisor a that is larger than Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sqrt n} , there must be another divisor b that is smaller than Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sqrt n} . Thus, it is sufficient to look for a divisor up to Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sqrt n} . This makes a significant difference: for example, we only need to try dividing by 2, 3, ..., 31 to verify that 997 is prime, rather than all the numbers 2, 3, ..., 996. Trial division might be described as follows using pseudocode:

Algorithm: trial division

- Given n,

- For each i = 2, 3, ... less than or equal to Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sqrt{n}}

:

- If i divides n:

- Return "n is not prime"

- Else:

- Continue with the next i

- If i divides n:

- When all i have been checked:

- Return "n is prime"

Sieve of Eratosthenes

The idea of the sieve of Eratosthenes is to write down a list of numbers starting from 2 ranging up to some limit, say

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

The first number (2) is prime, so we mark it, and cross out all of its multiples

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

The smallest unmarked number is 3, so we mark it and cross out all its multiples (some of which may already have been crossed out)

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

The smallest unmarked number (5) is the next prime, so we mark it and cross out all of its multiples

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

Notice that there are no multiples of 5 Failed to parse (SVG (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (\le 20)}

that haven't already been crossed out, but that doesn't matter at this stage. Proceeding as before, we add 7, 11, 13, 17 nd 19 to our list of primes

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

But now we are stuck, having run though all the numbers on the list. To proceed further, we must first extend the list

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

and then backtrack and cross out all multiples of primes identified previously

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

We now see that the next smallest unmarked number is 23, so it, too, must be prime, so we mark it

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

Continuing as before, we find that 29, 31, and 37 are also prime, but then we get stuck and the list has to be extended again. We may continue this way as long as we like, so the Sieve of Eratosthenes not only provides a method for testing a number to see if it is prime, but also for enumerating the (infinite) set of prime numbers.

Some Unsolved Problems

There are many unsolved problems concerning prime numbers. Two such problems (posed as conjectures) are:

The Twin Prime Conjecture

Twin primes are pairs of prime numbers differing by 2. Examples of twin primes include 5 and 7, 11 and 13, and 41 and 43. It is unknown whether there are infinitely many such pairs.

The Goldbach Conjecture

The Goldbach conjecture is that every even number greater than 2 can be expressed as the sum of two primes.

The Prime Number Theorem

If is the number of primes , then

This result, known as the Prime Number Theorem, was demonstrated independently by Jacques Hadamard and Charles de la Vallée Poussin in 1896, using properties of the Riemann zeta function. Their method depended in an essential way on complex analysis. It was not until 1949 that Atle Selberg and Paul Erdös were able prove the theorem without using complex analysis.

The Riemann Hypotesis

Further Reading

- Apostol, Tom M. (1976). Introduction to Analytic Number Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90163-9.

- Ribenboim, Paulo (2004). The Little Book of Bigger Primes, second edition. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-20169-6.

- Scharlau, Winfried; Hans Opolka (1985). From Fermat to Minkowski: Lectures on the Theory of Numbers and its Historical Development. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90942-7.

(Note that Scharlau and Opolka was originally published as: Scharlau, Winfried; Hans Opolka (1980). Von Fermat bis Minkowski: Eine Vorlesung über Zahlentheorie und ihre Entwicklung. Springer-Verlag. ).