Influenza: Difference between revisions

imported>Robert Badgett |

imported>Robert Badgett |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

<table border="1" cellpadding="5" class="wikitable"> | <table border="1" cellpadding="5" class="wikitable"> | ||

<caption>Combinations of findings for diagnosing influenza<ref name="pmid15728170"/></caption> | <caption>Combinations of findings for diagnosing influenza<ref name="pmid22218625">{{cite journal| author=Ebell MH, Afonso AM, Gonzales R, Stein J, Genton B, Senn N| title=Development and validation of a clinical decision rule for the diagnosis of influenza. | journal=J Am Board Fam Med | year= 2012 | volume= 25 | issue= 1 | pages= 55-62 | pmid=22218625 | doi=10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110161 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22218625 }} </ref><ref name="pmid15728170"/></caption> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<th rowspan="2">Combinations of findings </th> | <th rowspan="2">Combinations of findings </th> | ||

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td>Fever and cough</td> | <td>Fever and cough</td> | ||

<td align="center">64%</td> | <td align="center">64%<br/>61%<ref name="pmid22218625"/></td> | ||

<td align="center">67%</td> | <td align="center">67%<br/>80%<ref name="pmid22218625"/></td> | ||

<td align="center">79%</td> | <td align="center">79%<br/>86%<ref name="pmid22218625"/></td> | ||

<td align="center">49%</td> | <td align="center">49%<br/>49%<ref name="pmid22218625"/></td> | ||

<td align="center">39%</td> | <td align="center">39%<br/>50%<ref name="pmid22218625"/></td> | ||

<td align="center">15%</td> | <td align="center">15%<br/>14%<ref name="pmid22218625"/></td> | ||

<td align="center">4%</td> | <td align="center">4%<br/>6%<ref name="pmid22218625"/></td> | ||

<td align="center">1%</td> | <td align="center">1%<br/>1%<ref name="pmid22218625"/></td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

<td align="center">16</td> | <td align="center">16</td> | ||

<td align="center">4</td> | <td align="center">4</td> | ||

<td align="center">1</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td>Fever and cough and acute onset<ref name="pmid22218625"/></td> | |||

<td align="center">41</td> | |||

<td align="center">93</td> | |||

<td align="center">92</td> | |||

<td align="center">55</td> | |||

<td align="center">66</td> | |||

<td align="center">18</td> | |||

<td align="center">11</td> | |||

<td align="center">1</td> | <td align="center">1</td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

Revision as of 13:48, 17 January 2012

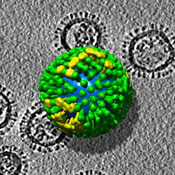

Influenza, commonly called “the ‘Flu”, is described as "an acute viral infection in humans involving the respiratory tract. It is marked by inflammation of the nasal mucosa; the pharynx; and conjunctiva, and by headache and severe, often generalized, myalgia".[1] It is contagious (easily passed from one person to another) and is caused by viruses of the Orthomyxoviridae family.

Classification

There are three types of influenza viruses:[2]

- Influenza A virus. "Influenza A viruses are further classified by subtype on the basis of the two main surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). Influenza A subtypes and B viruses are further classified by strains."[2]

- Influenza B virus

- Influenza C virus

Hosts

Influenza in humans

In April, 2009, the 2009 H1N1 influenza virus was first isolated and is a novel H1N1 strain that was initially untypeable. The 2009 novel H1N1 influenza virus contains genes normally found in North American swine as well as two genes found in European and Asian swine and has been called a triple-reassortant of genes.[3][4]

In the 2007-2008 season, the most common strains of influenza in the United States were:[5]

- influenza A virus (H1N1) 35%

- influenza A virus (H3N2) 35%

- influenza B virus 30%

In the 1999-2000 season, the most common strains of influenza in the United States were:[6]

- influenza A virus (H1N1) 3%

- influenza A virus (H3N2) 99%

- influenza B virus 0.6%

Equine Influenza

This is a species-specific strain that infects horses, ponies, donkeys and mules. Humans do not catch this disease but are carriers of it. It is airborne and highly contagious. Equine influenza generally does not kill its victims, and affected horses display similar symptoms to those of humans.

In 2007, a horse flu epidemic began in New South Wales, Australia. The outbreak is believed to have begun as a result of infractions of proper quarantine procedure and is expected to cost millions of dollars in lost revenue. As of September, 2007, it had spread to the Victorian border, causing the cancellation of events at the Melbourne Show, and the possibility that the Spring Carnival, including the running of the Melbourne Cup horse race, would be canceled.

Avian flu

Avian flu, also known as Bird flu or H5N1, has led to recent outbreaks.[7][8]

Epidemiology

Current influenza activity can be monitored online:

- In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintains public statistics at http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivity.htm.]]

- Google maintains statistics based on search terms (http://www.google.org/flutrends/).[10]

- http://healthmap.org/

The prevalence of influenza among people who have an "influenza-like illness" varies strongly with the seasons of the year. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintains public statistics at http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivity.htm.

- During the off season, the the prevalence is < 2%[9]

- During the height of season, the prevalence may be 20-35%.[9]

- During local outbreaks, the prevalence may be 50-80% according to studies.[11][12] Unfortunately, the CDC does not report sufficient details to determine where local outbreaks are occurring.

In addition to seasonal variations, there have been several worldwide influenza epidemics, resulting in millions of deaths.

Diagnosis

History and physical examination

Since anti-viral drugs are effective in treating influenza if given early (see treatment section, below), it can be important to identify cases early. A systematic review by the Rational Clinical Examination concluded that the best findings for excluding the diagnosis of influenza are:[13]

| Finding: | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Fever† | 86%† | 25% |

| Cough† | 98%† | 23% |

| Sore throat | ~80%† | ~30% |

| Nasal congestion† | 70–90%† | 20–40% |

| Absence of vaccination | 83-97% | 14-19%[14][15] |

| Note: † All three findings, especially fever, were less sensitive in patients over 60 years of age.[13] | ||

Using the symptoms listed above, the combinations of findings below can improve diagnostic accuracy.[16] Unfortunately, even combinations of findings are imperfect. However, Bayes Theorem can combine pretest probability with clinical findings to adequately diagnose or exclude influenza in some patients. The pretest probability has a strong seasonal variation; the current prevalence of influenza among patients in the United States receiving sentinel testing is available at the CDC.[17] Using the CDC data, the following table shows how the likelihood of influenza varies with prevalence:

| Combinations of findings | Sensitivity | Specificity | Projected during local outbreaks (prevalence approx 66%[19][12]) |

Projected during influenza season (prevalence=25%) |

Projected in off-season (prevalence=2%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPV | NPV | PPV | NPV | PPV | NPV | |||

| Fever and cough | 64% 61%[18] |

67% 80%[18] |

79% 86%[18] |

49% 49%[18] |

39% 50%[18] |

15% 14%[18] |

4% 6%[18] |

1% 1%[18] |

| Fever and cough and sore throat | 56 | 71 | 79 | 45 | 39 | 17 | 4 | 2 |

| Fever and cough and nasal congestion | 59 | 74 | 81 | 48 | 43 | 16 | 4 | 1 |

| Fever and cough and acute onset[18] | 41 | 93 | 92 | 55 | 66 | 18 | 11 | 1 |

Laboratory tests

Available tests are listed at the CDC website.

Clinical practice guidelines address diagnosis.[20]

Rapid tests using for influenza antigens include immunofluorescence assays, immunoenzyme technique, and polymerase chain reaction testing. The sensitivity of these tests range from 63% to 95%.[21][22]

Rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDT) using immunosorbent technique for influenza antigens have a sensitivity of about 50% and specificity of about 85%[23]

The polymerase chain reaction is the most sensitive test and is as sensitive as viral culture.[20]

Differential diagnosis

Influenza-like illness is defined as "fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat in the absence of a known cause other than influenza."[24] A study from Australia found that possible causes for influenza-like illness include respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, parainfluenza viruses, coronaviruses, and metapneumovirus.[25]

Other diagnoses to consider are:

- Parvovirus B19 - arthropathy is prominent

- Flaviviruses

- Dengue fever - bonebreak fever with retro-orbital pain

- West Nile virus - tremor is common

Treatment

The two classes of antiviral agents are neuraminidase inhibitors and M2 inhibitors (adamantane derivatives). Neuraminidase inhibitors are currently preferred for flu virus infections.

Different strains of influenza virus have differing degrees of resistance against these antivirals and it is impossible to predict what degree of resistance a future pandemic strain might have.[26]

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued recommendations for the use of antiviral agents.[27] The CDC recommends oseltamivir or zanamivir.

When to treat

According to two decision analysis studies of adults, treatment may be justified in the following settings:

- Elderly patients if the probability of influenza is over 14%[12]

- Adults if the probability of influenza is over 30%[11].

During local outbreaks of influenza, the prevalence will be over 50-80%[19][12] and thus patients with any of the above combinations of symptoms may be treated with neuramidase inhibitors without testing. In the absence of a local outbreak, treatment may be justified in the elderly during the influenza season as long as the prevalence is over 15%.[12]

Neuraminidase inhibitors

These drugs are effective, but modestly so, against both influenza A and B.[28][29] Examples are oseltamivir (trade name Tamiflu) and zanamivir (trade name Relenza) are neuraminidase inhibitors.[30] The Cochrane Collaboration concluded that these drugs reduce symptoms and complications.[31] Zanamivir, which must be delivered by inhalation, may cause bronchospasm in patients with asthma.

Oseltamivir may[32] or may not[28] reduce the incidence of respiratory complications on one of 13 patients who take it (number needed to treat = 13). This trial only included patients up to 65 years old.

Neither of these drugs can be administered by injection. For the 2009 pandemic, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency authorization for the use of intravenous peramavir, which had been in Phase III clinical trials. [33]

M2 inhibitors (adamantanes)

These drugs are sometimes effective against influenza A if given early in the infection, but are always ineffective against influenza B. Examples include the antiviral drugs amantadine and rimantadine which block a viral ion channel and prevent the virus from infecting cells. [34]

Prevention

Barriers

A regular surgical mask is adequate.[35]

Vaccination

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has published recommendations on who should get the influenza vaccination.[36] Protection from infection occurs by two weeks after vaccination and lasts one year.[36]

The quality of the research on vaccination my be reduced by conflict of interest according to the Cochrane Collaboration.[37]

The vaccine does not cause influenza nor increase the frequency of systemic symptoms over placebo.[38]

Chemoprevention

Chemoprevention (chemoprophylaxis) with neuraminidase inhibitors can prevent symptomatic influenza according to a meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration.[31]Zanamivir may cause bronchospasm in patients with asthma. Extended-duration (>4 weeks) chemoprevention may be effective as well.[39]

Pandemics and notable outbreaks

Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918-1920

A pandemic of Spanish Influenza, involving a highly pathogenic mutation of serotype H1N1, swept across the world in the wake of the Great War (1918-20). More people are believed to have died of the flu in the year after the war then in the Great War itself. Estimates vary but it is estimated that one third of the world's population were infected and up to 50 million people perished in this pandemic (it is possibly that fatalities world wide were as high as 100 million).[40] Some comparisons are drawn between Spanish Flu and the Black Death (Bubonic Plague) of 1347 to 1351. Estimates are that the flu killed more people in one year than plague did in four.

In the United States, the epidemic led to closing of schools and banning of public meetings in order to successfully reduce mortality.[41]

Asian influenza pandemic of 1957 - 1963

A/H2N2 virus was responsible for this outbreak

Hong Kong pandemic 1968-1970

This was caused by serotype A/H3N2.

References

- ↑ National Library of Medicine. "Influenza". [e]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Anonymous (2005)Influenza Viruses, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ↑ Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team. Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S et al. (2009). "Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans.". N Engl J Med 360 (25): 2605-15. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0903810. PMID 19423869. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Swine Flu & You

- ↑ 2007-08 U.S. INFLUENZA SEASON SUMMARY, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ↑ 1999-2000 INFLUENZA SEASON SUMMARY, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ↑ Oner AF, Bay A, Arslan S, et al (2006). "Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in eastern Turkey in 2006". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (21): 2179–85. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa060601. PMID 17124015. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Kandun IN, Wibisono H, Sedyaningsih ER, et al (2006). "Three Indonesian clusters of H5N1 virus infection in 2005". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (21): 2186–94. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa060930. PMID 17124016. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu Activity. Retrieved on 2007-11-29.

- ↑ Helft M (Nov 11, 2008). Google Uses Web Searches to Track Flu’s Spread - NYTimes.com. New York Times Company. Retrieved on 2008-11-11.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Smith K, Roberts M (2002). "Cost-effectiveness of newer treatment strategies for influenza.". Am J Med 113 (4): 300-7. DOI:10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01222-6. PMID 12361816. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Rothberg M, Bellantonio S, Rose D (2003). "Management of influenza in adults older than 65 years of age: cost-effectiveness of rapid testing and antiviral therapy.". Ann Intern Med 139 (5 Pt 1): 321-9. PMID 12965940.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Call SA, Vollenweider MA, Hornung CA, Simel DL, McKinney WP (2005). "Does this patient have influenza?". JAMA 293 (8): 987-97. DOI:10.1001/jama.293.8.987. PMID 15728170. Research Blogging. Review in: Evid Based Nurs. 2005 Oct;8(4):121

- ↑ Hulson TD, Mold JW, Scheid D, et al (December 2001). "Diagnosing influenza: the value of clinical clues and laboratory tests". J Fam Pract 50 (12): 1051–6. PMID 11742606. [e]

- ↑ van Elden LJ, van Essen GA, Boucher CA, et al (August 2001). "Clinical diagnosis of influenza virus infection: evaluation of diagnostic tools in general practice". Br J Gen Pract 51 (469): 630–4. PMID 11510391. PMC 1314072. [e]

- ↑ Monto A, Gravenstein S, Elliott M, Colopy M, Schweinle J (2000). "Clinical signs and symptoms predicting influenza infection.". Arch Intern Med 160 (21): 3243–7. PMID 11088084.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weekly Report: Influenza Summary Update. Accessed January 1, 2007.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 18.9 Ebell MH, Afonso AM, Gonzales R, Stein J, Genton B, Senn N (2012). "Development and validation of a clinical decision rule for the diagnosis of influenza.". J Am Board Fam Med 25 (1): 55-62. DOI:10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110161. PMID 22218625. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Smith K, Roberts M (2002). "Cost-effectiveness of newer treatment strategies for influenza.". Am J Med 113 (4): 300-7. DOI:10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01222-6. PMID 12361816. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Harper SA, Bradley JS, Englund JA, File TM, Gravenstein S, Hayden FG et al. (2009). "Seasonal influenza in adults and children--diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.". Clin Infect Dis 48 (8): 1003-32. DOI:10.1086/598513. PMID 19281331. Research Blogging.

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "pmid19281331" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Beyer WE. Heterogeneity of case definitions used in vaccine effectiveness studies--and its impact on meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2006 Nov 10;24(44-46):6602-4. Epub 2006 Jun 8. PMID 16797799

- ↑ Rodriguez WJ, Schwartz RH, Thorne MM. Evaluation of diagnostic tests for influenza in a pediatric practice. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002 Mar;21(3):193-6. PMID 12005080

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009). "Performance of rapid influenza diagnostic tests during two school outbreaks of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection - Connecticut, 2009.". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 58 (37): 1029-32. PMID 19779397.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2007). CDC - Influenza (Flu) - Flu Activity. Retrieved on 2007-11-19.

- ↑ Kelly H, Birch C (2004). "The causes and diagnosis of influenza-like illness". Australian family physician 33 (5): 305–9. PMID 15227858. [e]

- ↑ Webster, Robert G. (2006). "H5N1 Influenza — Continuing Evolution and Spread". N Engl J Med 355 (21): 2174–77. PMID 16192481.

- ↑ Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (2011) Antiviral Agents for the Treatment and Chemoprophylaxis of Influenza. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Del Mar C (2009). "Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults: systematic review and meta-analysis.". BMJ 339: b5106. DOI:10.1136/bmj.b5106. PMID 19995812. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Del Mar C, Dooley L, Foxlee R (2010). "Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD001265. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001265.pub3. PMID 20166059. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Moscona, A (2005). "Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza". N Engl J Med 353 (13): 1363–73. PMID 16192481.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Jefferson, T; Demicheli V, Di Pietrantonj C, Jones M, Rivetti D. "Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD001265. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001265.pub2. PMID 16855962. Research Blogging.

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "pmid16855962" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Treanor JJ, Hayden FG, Vrooman PS, et al (2000). "Efficacy and safety of the oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir in treating acute influenza: a randomized controlled trial. US Oral Neuraminidase Study Group". JAMA 283 (8): 1016–24. PMID 10697061. [e]

- ↑ Emergency Use Authorization of Peramivir IV, Centers for Disease Control

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid10459804 - ↑ Loeb, Mark; Nancy Dafoe, James Mahony, Michael John, Alicia Sarabia, Verne Glavin, Richard Webby, Marek Smieja, David J. D. Earn, Sylvia Chong, Ashley Webb, Stephen D. Walter (2009-10-01). "Surgical Mask vs N95 Respirator for Preventing Influenza Among Health Care Workers: A Randomized Trial". JAMA: 2009.1466. DOI:10.1001/jama.2009.1466. Retrieved on 2009-10-02. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010). Prevention and Control of Influenza with Vaccines. Retrieved on 2010-08-02.

- ↑ Jefferson T, Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A, Bawazeer GA, Al-Ansary LA, Ferroni E (2010). "Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7: CD001269. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub4. PMID 20614424. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Margolis KL, Nichol KL, Poland GA, Pluhar RE (1990). "Frequency of adverse reactions to influenza vaccine in the elderly. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial.". JAMA 264 (9): 1139-41. PMID 2200894. [e]

- ↑ Khazeni N, Bravata DM, Holty JE, Uyeki TM, Stave CD, Gould MK (2009). "Safety and Efficacy of Extended-Duration Antiviral Chemoprophylaxis Against Pandemic and Seasonal Influenza.". Ann Intern Med. PMID 19652173.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol12no01/05-0979.htm

- ↑ Markel H, Lipman HB, Navarro JA, et al (2007). "Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic". JAMA 298 (6): 644–54. DOI:10.1001/jama.298.6.644. PMID 17684187. Research Blogging.

- Pages with reference errors

- Pages using PMID magic links

- CZ Live

- Health Sciences Workgroup

- Biology Workgroup

- Military Workgroup

- Microbiology Subgroup

- Infectious Disease Subgroup

- Articles written in British English

- All Content

- Health Sciences Content

- Biology Content

- Military Content

- Military tag

- Infectious Disease tag