Operation CARTWHEEL: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{TOC|right}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

The '''Battle of Rabaul''' was a successful air campaign by the U.S. against a Japanese island stronghold in the Pacific in World War II. In August 1943 the U.S. decided to drop earlier plans to capture the main Japanese forward base of [[Rabaul]], on New Britain, just east of [[New Guinea]], and instead to neutralize and bypass it, leaving its ultimate reduction to air attacks. | The '''Battle of Rabaul''' was a successful air campaign by the U.S. against a Japanese island stronghold in the Pacific in World War II. In August 1943 the U.S. decided to drop earlier plans to capture the main Japanese forward base of [[Rabaul]], on New Britain, just east of [[New Guinea]], and instead to neutralize and bypass it, leaving its ultimate reduction to air attacks. | ||

==The Base== | |||

" by the fall of 1943 was well prepared and heavily defended. Lakunai and Vunakanau airfields, two prewar Australian strips, had been improved despite repeated bombings by Fifth Air Force planes extending back to early 1942; the first had an all-weather surface of sand and volcanic ash, the second was surfaced with concrete. Rapopo, fourteen miles southeast of Rabaul, had been completed by December 1942 with concrete strips, barracks, and other facilities for operations, communications, repair, and supply. Tobera's concrete-surfaced airfield, inland midway between Vunakanau and Rapopo, had been completed in August 1943. On these four fields around Rabaul* were revetments for 166 bombers and 265 fighters, besides extensive unprotected dispersal parking areas. Across the St. Georges Channel on New Ireland were the additional facilities of Borpop airfield, completed in December 1943, which formed the fifth of the operational dromes protecting Rabaul. | |||

"The docking facilities of the port of Rabaul included seven wharves, which the Japanese supplemented by building new piers in Simpson Harbor and by using floating cranes. On the north shore of Blanche Bay, where the many inlets were well covered by heavy foliage, the Japanese dispersed their repair facilities and harborage for small boats and barges. In the same area they also located their submarine fueling and handling facilities. The Japanese were well supplied in all classes of stocks, since the Eighth Supply Depot of the Southeastern Fleet and the supply section of the Eighth Area Army each maintained a six-month inventory of all supplies for the army and naval units in the Bismarcks-Solomons-eastern New Guinea areas until February 1944. Most of these supplies were in warehouses in Rabaul township or stored in dumps above ground. | |||

"To protect all this, high priority had been given to antiaircraft defenses during 1943. The organizational setup was a combined army and naval defensive establishment which was well coordinated and integrated. Of the 367 antiaircraft weapons, 192 were army operated and 175 naval operated. The army units were used around Rapopo airfield and around army dumps and installations; they also participated jointly in the defenses lining Simpson Harbor. The naval units guarded Simpson Harbor and its shipping and the three airfields of Tobera, Lakunai, and Vunakanau. The Southeastern Fleet had built up an extensive and efficient early warning radar system. Besides the sets at Rabaul with ninety-mile coverage, there were radar sets to the southwest on New Britain, at Kavieng and Cape St. George on New Ireland, and at Buka. These sets would pick up Allied strikes and would radio warning to Rabaul from thirty to sixty minutes ahead of the attack. Surrounding Rabaul, the Japanese had also established strong beach and coastal defenses as well as heavily fortified ground defense zones." <ref>{{citation | |||

| title = Army Air Forces in World War II. | |||

| volume = Volume IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan August 1942 to July 1944 | |||

| editor = Wesley Frank Craven, James Lea Cate | |||

| contribution = Chapter X: Rabaul and Cape Glouster | |||

| author = Kramer J. Rohfleisch, James C. Olson, Berhardt L. Mortensen | |||

| url = http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/IV/AAF-IV-10.html}}, pp. 311-312</ref> | |||

==Early attacks== | |||

By fall, indeed, American and Australian advances in New Guinea to the west and in the [[Solomon Islands|Solomons]] to the south had all but isolated Rabaul. Beginning in October, 1943, American and Australian air power, both land- and sea-based, struck repeatedly with increasing intensity at the enemy base, concentrating on eliminating Japanese air strength there. The main AAF (U.S. Air Force) weapon was bombers based in Townsville, Australia, | By fall, indeed, American and Australian advances in New Guinea to the west and in the [[Solomon Islands|Solomons]] to the south had all but isolated Rabaul. Beginning in October, 1943, American and Australian air power, both land- and sea-based, struck repeatedly with increasing intensity at the enemy base, concentrating on eliminating Japanese air strength there. The main AAF (U.S. Air Force) weapon was bombers based in Townsville, Australia, | ||

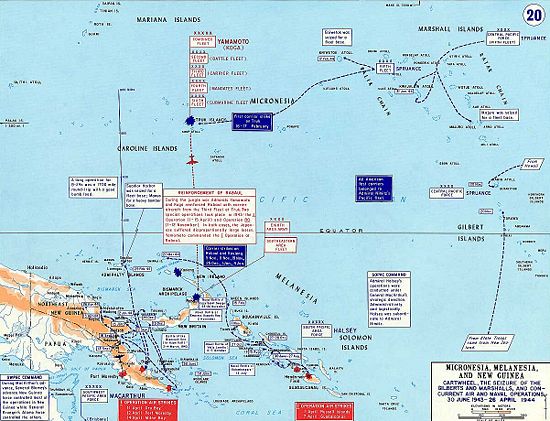

[[Image:Rabaul-WW2.jpg|thumb|550px]] | [[Image:Rabaul-WW2.jpg|thumb|550px]] | ||

==Main offensive== | |||

Operation CARTWHEEL was the main effort.<ref name=Cart>{{citation | |||

| journal = United States Army in World War II; The War in the Pacific | |||

| title = CARTWHEEL: The Reduction of Rabaul | |||

| author = John Miller, Jr. | |||

| year = 1959 | |||

| url = http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Rabaul/USA-P-Rabaul-12.html | |||

| contribution = CHAPTER XII, The Invasion of Bougainville: the Decision to bypass Rabaul}}</ref> | |||

On 12 October 1943, in the first of a series of raids in support of the pending Bougainville landing, Allied Air Forces in the SWPA theatre mounted the largest strike of the war against Rabaul. AAF General George Kenney later stated that every SWPA plane "that was in commission, and that could fly that far, was on the raid", including 87 [[B-24]]s, 114 [[B-25 Mitchell]]s, 12 RAAF Beaufighters, 125 [[P-38 Lightning]]s, and 11 weather and reconnaissance planes. Operational accidents and mechanical failures on the long haul from takeoff to target forced 50 of the fighters and bombers to turn back, but the successive attacking waves had strength to spare to overwhelm the 32 [[Zeke]]s that rose to intercept. | On 12 October 1943, in the first of a series of raids in support of the pending Bougainville landing, Allied Air Forces in the SWPA theatre mounted the largest strike of the war against Rabaul. AAF General George Kenney later stated that every SWPA plane "that was in commission, and that could fly that far, was on the raid", including 87 [[B-24]]s, 114 [[B-25 Mitchell]]s, 12 RAAF Beaufighters, 125 [[P-38 Lightning]]s, and 11 weather and reconnaissance planes. Operational accidents and mechanical failures on the long haul from takeoff to target forced 50 of the fighters and bombers to turn back, but the successive attacking waves had strength to spare to overwhelm the 32 [[Zeke]]s that rose to intercept. | ||

==Aftermath== | |||

Within a month Rabaul was no longer an offensive threat. By the end of 1943 the line of Allied air bases had advanced close enough to permit the initiation of a sustained air offensive aimed at knocking out the Japanese base completely. This offensive, combined with continuing Allied advances in the central and southwest Pacific, soon rendered Rabaul useless to the enemy as a strategic base. | Within a month Rabaul was no longer an offensive threat. By the end of 1943 the line of Allied air bases had advanced close enough to permit the initiation of a sustained air offensive aimed at knocking out the Japanese base completely. This offensive, combined with continuing Allied advances in the central and southwest Pacific, soon rendered Rabaul useless to the enemy as a strategic base. | ||

Under almost daily attack, the Japanese in Rabaul began evacuating aircraft and shipping. By March 1944, when the great Allied air offensive came to an end, roughly 20,000 tons of bombs had been dropped. The nearly 100,000 Japanese troops still defending Rabaul were isolated and impotent, no longer factors in the war. Japan sent in supplies by submarine, but Japanese died of malnutrition and starvation until they surrendered in August, 1945. | Under almost daily attack, the Japanese in Rabaul began evacuating aircraft and shipping. By March 1944, when the great Allied air offensive came to an end, roughly 20,000 tons of bombs had been dropped. The nearly 100,000 Japanese troops still defending Rabaul were isolated and impotent, no longer factors in the war. Japan sent in supplies by submarine, but Japanese died of malnutrition and starvation until they surrendered in August, 1945. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | |||

Revision as of 16:12, 20 June 2010

The Battle of Rabaul was a successful air campaign by the U.S. against a Japanese island stronghold in the Pacific in World War II. In August 1943 the U.S. decided to drop earlier plans to capture the main Japanese forward base of Rabaul, on New Britain, just east of New Guinea, and instead to neutralize and bypass it, leaving its ultimate reduction to air attacks.

The Base

" by the fall of 1943 was well prepared and heavily defended. Lakunai and Vunakanau airfields, two prewar Australian strips, had been improved despite repeated bombings by Fifth Air Force planes extending back to early 1942; the first had an all-weather surface of sand and volcanic ash, the second was surfaced with concrete. Rapopo, fourteen miles southeast of Rabaul, had been completed by December 1942 with concrete strips, barracks, and other facilities for operations, communications, repair, and supply. Tobera's concrete-surfaced airfield, inland midway between Vunakanau and Rapopo, had been completed in August 1943. On these four fields around Rabaul* were revetments for 166 bombers and 265 fighters, besides extensive unprotected dispersal parking areas. Across the St. Georges Channel on New Ireland were the additional facilities of Borpop airfield, completed in December 1943, which formed the fifth of the operational dromes protecting Rabaul.

"The docking facilities of the port of Rabaul included seven wharves, which the Japanese supplemented by building new piers in Simpson Harbor and by using floating cranes. On the north shore of Blanche Bay, where the many inlets were well covered by heavy foliage, the Japanese dispersed their repair facilities and harborage for small boats and barges. In the same area they also located their submarine fueling and handling facilities. The Japanese were well supplied in all classes of stocks, since the Eighth Supply Depot of the Southeastern Fleet and the supply section of the Eighth Area Army each maintained a six-month inventory of all supplies for the army and naval units in the Bismarcks-Solomons-eastern New Guinea areas until February 1944. Most of these supplies were in warehouses in Rabaul township or stored in dumps above ground.

"To protect all this, high priority had been given to antiaircraft defenses during 1943. The organizational setup was a combined army and naval defensive establishment which was well coordinated and integrated. Of the 367 antiaircraft weapons, 192 were army operated and 175 naval operated. The army units were used around Rapopo airfield and around army dumps and installations; they also participated jointly in the defenses lining Simpson Harbor. The naval units guarded Simpson Harbor and its shipping and the three airfields of Tobera, Lakunai, and Vunakanau. The Southeastern Fleet had built up an extensive and efficient early warning radar system. Besides the sets at Rabaul with ninety-mile coverage, there were radar sets to the southwest on New Britain, at Kavieng and Cape St. George on New Ireland, and at Buka. These sets would pick up Allied strikes and would radio warning to Rabaul from thirty to sixty minutes ahead of the attack. Surrounding Rabaul, the Japanese had also established strong beach and coastal defenses as well as heavily fortified ground defense zones." [1]

Early attacks

By fall, indeed, American and Australian advances in New Guinea to the west and in the Solomons to the south had all but isolated Rabaul. Beginning in October, 1943, American and Australian air power, both land- and sea-based, struck repeatedly with increasing intensity at the enemy base, concentrating on eliminating Japanese air strength there. The main AAF (U.S. Air Force) weapon was bombers based in Townsville, Australia,

Main offensive

Operation CARTWHEEL was the main effort.[2]

On 12 October 1943, in the first of a series of raids in support of the pending Bougainville landing, Allied Air Forces in the SWPA theatre mounted the largest strike of the war against Rabaul. AAF General George Kenney later stated that every SWPA plane "that was in commission, and that could fly that far, was on the raid", including 87 B-24s, 114 B-25 Mitchells, 12 RAAF Beaufighters, 125 P-38 Lightnings, and 11 weather and reconnaissance planes. Operational accidents and mechanical failures on the long haul from takeoff to target forced 50 of the fighters and bombers to turn back, but the successive attacking waves had strength to spare to overwhelm the 32 Zekes that rose to intercept.

Aftermath

Within a month Rabaul was no longer an offensive threat. By the end of 1943 the line of Allied air bases had advanced close enough to permit the initiation of a sustained air offensive aimed at knocking out the Japanese base completely. This offensive, combined with continuing Allied advances in the central and southwest Pacific, soon rendered Rabaul useless to the enemy as a strategic base.

Under almost daily attack, the Japanese in Rabaul began evacuating aircraft and shipping. By March 1944, when the great Allied air offensive came to an end, roughly 20,000 tons of bombs had been dropped. The nearly 100,000 Japanese troops still defending Rabaul were isolated and impotent, no longer factors in the war. Japan sent in supplies by submarine, but Japanese died of malnutrition and starvation until they surrendered in August, 1945.

References

- ↑ Kramer J. Rohfleisch, James C. Olson, Berhardt L. Mortensen, Chapter X: Rabaul and Cape Glouster, in Wesley Frank Craven, James Lea Cate, Army Air Forces in World War II., vol. Volume IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan August 1942 to July 1944, pp. 311-312

- ↑ John Miller, Jr. (1959), CHAPTER XII, The Invasion of Bougainville: the Decision to bypass Rabaul, "CARTWHEEL: The Reduction of Rabaul", United States Army in World War II; The War in the Pacific