Energy storage: Difference between revisions

imported>David MacQuigg No edit summary |

imported>David MacQuigg m (move TOC to right) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{seealso|Nuclear_power_reconsidered}} | {{seealso|Nuclear_power_reconsidered}} | ||

{{TOC}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

This article is a brief comparison of the technologies relevant to the large-scale energy storage<ref>https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/electricity-and-energy-storage.aspx</ref> needed for wind and solar and other intermittent energy sources. | This article is a brief comparison of the technologies relevant to the large-scale energy storage<ref>https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/electricity-and-energy-storage.aspx</ref> needed for wind and solar and other intermittent energy sources. | ||

The most important point of comparison is cost per kilowatt hour (kWh), including the cost of ancillary equipment like power inverters or heat storage tanks. Other costs, like battery replacement can be added to cost per kWh by assuming a reasonable time over which these costs are depreciated. | The most important point of comparison is cost per kilowatt hour (kWh), including the cost of ancillary equipment like power inverters or heat storage tanks. Other costs, like battery replacement can be added to cost per kWh by assuming a reasonable time over which these costs are depreciated. | ||

Revision as of 19:56, 20 February 2022

- See also: Nuclear_power_reconsidered

This article is a brief comparison of the technologies relevant to the large-scale energy storage[1] needed for wind and solar and other intermittent energy sources. The most important point of comparison is cost per kilowatt hour (kWh), including the cost of ancillary equipment like power inverters or heat storage tanks. Other costs, like battery replacement can be added to cost per kWh by assuming a reasonable time over which these costs are depreciated.

Other factors to consider in buying energy storage are the peak power needed and the round-trip-efficiency. Pumped hydro and batteries return about 80% of the energy put in.[2] Thermal storage, where there is no conversion to other forms of energy, can be near 100% efficient.

In a power grid with a mix of intermittent and dispatchable sources, and insufficient storage, the capital cost of the dispatchable sources is determined by the peak demand on the grid. Adding intermittent sources reduces only the fuel costs of the dispatchable sources, not their capital costs.

Pumped hydro

This is the energy storage most widely used by utilities, where available. Near a river with a big reservoir, cost per kWh can be very low, limited only by the cost of operating the motor/pump/turbine/generator. Where water is limited, the capital cost of building the reservoirs, upper and lower, should be divided by the total storage capacity and this result added the cost per kWh.[3]

Thermal

Molten salt is a very efficient way to store energy in concentrated solar power (CSP) systems,[4] where adding some well-insulated storage tanks does not significantly increase the thermal losses. It is also being considered for storage at nuclear plants to allow rapid load following in grids that have a large component of wind and solar.[5]

Batteries

Batteries are still too expensive for utility-scale systems. Even with an optimistic projection of future Li-ion battery technology ($100 per kWh) a small city with 1 GW average consumption might need 100 hours of storage, requiring a $10 billion capital investment, ten times the cost of the plant.[6] Some newer battery technologies promise lower cost per kWh, but at the scale needed to power the world, there may be resource limitations.[7]

Hydrogen

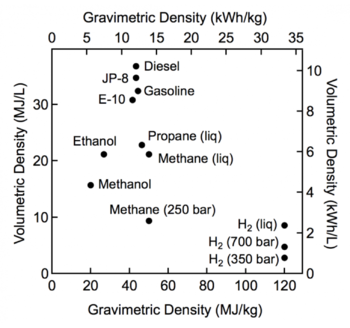

Hydrogen energy storage may become an important competitor to pumped hydro and thermal, if high-temperature nuclear reactors become available. The readily available high-temperature heat from these reactors will offset the inefficiency of generating the hydrogen from water. The volumetric energy density is too low for transportation uses (see Fig.1) but not a problem for utilities.

Other

Although not storing energy to be used for generating electricity, high-temperature reactors can perform the equivalent of energy storage by using excess available energy to power processes that don't care if the energy is intermittent, like the production of steel, cement, and fertilizer. This "process heat" is a big part of our total energy consumption, and can be timed to take advantage of periods when the intermittent sources are at full power.

Further reading

- Electricity and Energy Storage World Nuclear Association.

Notes and References

- ↑ https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/electricity-and-energy-storage.aspx

- ↑ https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=46756

- ↑ To store 100 megawatts for 10 hours you will need a hill 500 feet high with 250 acre reservoirs at each end that you can draw up or down 10 feet.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concentrated_solar_power

- ↑ https://natriumpower.com/

- ↑ Liquid metal batteries might cut this cost in half. https://ambri.com/technology

- ↑ The Liquid Metal Battery uses low-cost calcium as the anode, but antimony for the cathodes may be in short supply if this technology is scaled up.

- ↑ https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-storage