Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was a proposal, never adopted, for Congress to forbid the expansion of slavery into the Southwest, especially New Mexico. It inflamed sectional tensions and helped cause the American Civil War. During the Mexican-American War President James K. Polk asked Congress for $2 million to negotiate peace; everyone understood the money would be used to buy Mexican territories. On Aug. 8, 1846, David Wilmot, a Democratic Congressman from Pennsylvania, proposed an amendment:

- Provided, That, as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico…neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory.

This Wilmot Proviso was passed by the House on a sectional vote (the North voted yea, the South voted nay), but not by the Senate and never became law. The Senate comprised 30 Senators from 15 slave states and 28 from 14 free states in 1847; With 30 percent of the voting population in 1848, the slave states cast 42 percent of the electoral votes. The Proviso became a highly contentious issue in the period 1846-1854 that escalated tensions between North and South, leading to Civil War. The origins came from a group of Van Buren Democrats, largely New Yorkers, who sponsored the Wilmot Proviso in a defensive move to provide cover for northern Democrats from the charge of acquiescing in a Slave Power conspiracy to add more slave States.[1]

During the bitter debates over the Wilmot Proviso it was added to numerous bills, none of which passed. A failed effort was made to limit the Proviso to the region north of the Missouri Compromise line. In 1846 and 1847 the bill passed narrowly passed in the House but was defeated in the Senate. $3 million was appropriated without Wilmot's conditions.

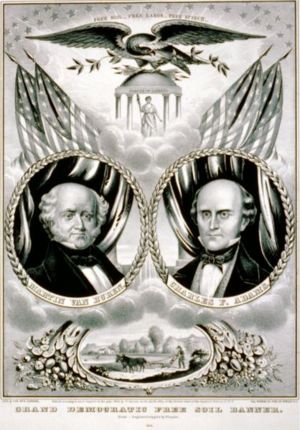

Debates over the proviso had aroused the country. State legislatures approved or condemned the opposition to slavery expansion incorporated in the proviso. Sectional animosity was heightened. The Northern Whigs strongly endorsed it, the Southern Whigs opposed; the party refused to take a stand at its national conventions in 1848 and 1852, and so the Whig coalition collapsed after 1852. In 1848 the antislavery Democrats in the Northeast formed the Free Soil Party with the slogan "Free Trade, Free Labor, Free Soil, Free Speech, and Free Men." In 1854-56 most of them joined the new Republican party, which was strongly committed to the proviso. The other northern Democrats dropped the Wilmot Proviso in 1848 in favor of the popular sovereignty principles of Stephen A. Douglas and Lewis Cass (which said local voters in the territories, not Congress, should decide on slavery there.) The Wilmot proviso was never about helping black slaves; it was all about stopping their owners from expanding into new western lands and thereby shutting out poor white farmers.[2] As David Wilmot put it. "The negro race already occupy enough of this fair continent. . . . I would preserve for free white labor a fair country . . . where the sons of toil, of my own race and own color, can live without the disgrace which association with negro slavery brings upon free labor." [3]

The “Alabama Platform” was adopted by the Democratic state convention in 1848 and approved by other southern groups. It was W. L. Yancey's answer to the Wilmot Proviso and popular sovereignty. The Alabama Platform demanded congressional protection of slavery in the Mexican cession. Rejected by the national Democrats in 1848, the anti-Wilmot Alabama platform was adopted by a majority of the Democratic Convention at Charleston in 1860. With the disruption of that convention, it became a basic issue of the southern secessionists.

“Conscience Whigs” were dissident New England members of the Whig party, so-called because of their moral opposition to slavery. They placed loyalty to their principles higher than loyalty to party and determined to resist at all hazards the further extension of slave territory. They favored the Wilmot Proviso. When the 1848 Whig National Convention refused to endorse it, they bolted and joined the Free Soil party.[4]

The Wilmot Proviso was meaningless in practice. California in 1849 unanimously adopted a state constitution that forbade slavery. Texas had already been admitted as a state in 1845 with slavery. The Compromise of 1850 allowed slavery in New Mexico and Arizona, but it was not economical and there never were more than a handful of slaves there. However the symbolic importance was everything. "As if by magic," commented a Boston Whig newspaper, "it brought to a head the great question that is about to divide the American people." Both sides in the debate assumed that in the long run, slavery had to expand to survive. The Wilmot Proviso would have stopped its expansion in one direction and was a clear marker that majorities in the North wanted slavery expansion to stop (and thus slavery to die away.) The southerners saw the issue as a matter of states rights, equality and honor. The Wilmot Proviso pronounced "a degrading inequality" on the South, declared a Virginian. It "says in effect to the Southern man, Avaunt! you are not my equal, and hence are to be excluded as carrying a moral taint." Having furnished most of the soldiers who conquered Mexican territory, the South was especially outraged by the proposal to shut them out of its benefits. [5] They were being treated as second class citizens because they owned slaves, and they could not tolerate that insult.

Bibliography

- Brauer, Kinley J. Cotton versus Conscience: Massachusetts Whig Politics and Southwestern Expansion, 1843-1848 (1967).

- Foner, Eric. "The Wilmot Proviso Revisited." Journal of American History 1969 56(2): 262-279. Issn: 0021-8723 Fulltext: in JSTOR

- Garrison, George Pierce. Westward Extension, 1841-1850 (1906) ch 16 online edition

- Holt, Michael F. The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. 1999 online edition

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, (1988).

- Morrison, Chaplain W. Democratic Politics and Sectionalism: The Wilmot Proviso Controversy (1967)

- Morrison, Michael A. Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War (1997), online edition

- Nevins, Allan. War for the Union (1947), vol 1 and 2 for the most thorough coverage

- Stewart, James Brewer. Joshua R. Giddings and the Tactics of Radical Politics. (1970)

- ↑ Foner 1969

- ↑ In practice it made little difference. California rejected slavery and New Mexico, where slavery was legal, had only a handful of slaves.

- ↑ Quoted in McPherson, (1988). p: 55. Those abolitionists who were concerned about the black slaves also supported the Wilmot Proviso, but they were a small factor.

- ↑ The conservatives, or Old Line Whigs, opponents of the Wilmot Proviso, were called Cotton Whigs, since they stood for a settlement of the slavery issue at any price for the sake of the cotton trade. The terms "Woolly Heads" and "Amalgamationistss" were also given to the antislavery group; the term "Snufftakers" was given to the conservatives. The Silver Gray Whigs were those party members who bolted in the Syracuse NY Convention (1850), following the endorsement of William H. Seward's position opposing the Compromise of 1850 and the adoption of antislavery resolutions. See Hans Sperber and Travis Trittschuh, American Political Terms: An Historical Dictionary (1962).

- ↑ McPherson, Battle Cry, 56-7