Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia[1] is a mental disorder characterized by patterns of disordered thought, language, motor, and social function. Men usually develop symptoms in their late teens and early 20s, while women have a later onset in the mid-20s to early 30s. During the acute stage of schizophrenia, individuals experience a break from reality although this does not mean they have multiple personalities. Despite popular perception, dissociative identity disorder (formerly known as multiple personality disorder) and schizophrenia are completely separate disorders.

The cause of schizophrenia is unknown, although several neurotransmitters and brain structures are hypothesized to play a role in this disorder and are considered in causes section. With the proper treatment, some people are able to lead rich, fulfilling lives.

Diagnosis and classification

Note: The American Psychiatric Association, which publishes the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, forbids the unauthorized reproduction of their diagnostic criteria. A narrative of the DSM-IV-TR criteria follows.

For a person to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, a person must display two or more of the following symptoms for a significant portion of one month, and they must cause a significant level of disturbance in one's life: delusions, hallucinations (usually auditory as visual are rare), disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behaviour, or negative symptoms. (These symptoms are classified as criterion A in the DSM).

Some signs must be present for at least six months since the onset of the disturbances, with at least one month of symptoms that meet the criterion A symptoms. However, only one of these symptoms is required if the delusions are bizarre, the patient hallucinates an auditory commentary of their actions or hears two or more voices participating in conversation with each other. The symptoms of these periods may manifest as only negative symptoms, or by two or more of the criterion A symptoms.

As with any disorder, there are several criteria that exclude a diagnosis. A patient will not receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia if they are schizoaffective or have a mood disorder with psychotic features, as no mood disorders occur at the same time as active phase symptoms, or have a brief duration compared to the active and residual phases. Substance use and medical conditions can mimic schizophrenia, and so a diagnosis will not be made if symptoms are due to their direct effects. A history of autism or another pervasive developmental disorder will exclude a diagnosis of schizophrenia unless prominent delusions or hallucinations are present for more than a month.

Subtypes

There are several general patterns of schizophrenia. These subtypes have been identified to aid research, treatment, and communication. Each pattern is not always as distinct as is presented below

Disorganized schizophrenia is prominent disorganized speech and behavior, with flat or inappropriate affect (display of emotion). This subtype is the closest form of the stereotypical idea of a "crazy person". A patient will not receive this classification if they meet the criteria for the catatonic type.

Catatonic schizophrenia is characterized by at least two of the following symptoms: catalepsy (a lack of voluntary movement), excessive and purposeless motor activity (uninfluenced by external stimuli), very strong negativism (maintaining a rigid position and resisting all attempts to be moved) or mutism, peculiar voluntary movement and posturing (often taking bizarre or inappropriate positions), stereotyped movements, with conspicuous mannerisms or grimacing, or echolalia or echopraxis (immediate repetition of other's words or actions).

Paranoid schizophrenia is characterized by delusions or hallucinations of a relatively consistent nature, usually related to themes of persecution or grandeur. Positive symptoms are most prominent as the patient retains largely coherent speech, a fairly normal display of emotions behavior. The prognosis is favorable, as it responds well to antipsychotic medication.

Undifferentiated schizophrenia occurs when the symptoms meet criterion A, and the patient does not fit into the paranoid, disorganized, or catatonic subtypes.

Residual schizophrenia has the absence of prominent delusions and hallucinations, disorganized speech or catatonic behaviour. However, there is a continued disturbance as marked by having two or more criterion A symptoms, but present in a weakened form. These symptoms could take the form of odd beliefs, or unusual (but not psychotic) perceptual experiences.

Dimensions

Another way of classifying schizophrenic behaviors is by identifying symptoms that exist on a continuum with varying degrees of severity rather than discrete groups.

The positive-negative dimension comprises positive symptoms, meaning the presence of something normally absent, characterized by prominent delusions, hallucinations, positive formal thought disorder, and persistently bizarre behavior. Negative symptoms are the absence of something that is normall present, such as flattened or masked affect, alogia, avolition, anhedonia, and attentional impairment.[2] The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is a 30-item psychiatric rating scale that can gauge the relationship of positive and negative symptoms, their differential, and the severity of illness.[3]

The paranoid-nonparanoid dimension is the presence or absence of delusion of persecution or grandeur. This dimension may be related to the process-reactive dimension.[4]

The process-reactive, or good-poor premorbid dimension attempts to classify the variation in acute symptom onset. Some individuals experience a prolonged prodromal phase, while others go from normal functioning to full-blown psychosis within days. Cases with a gradual onset are called process, while sudden onset precipitated by a traumatic or stressful event is called reactive. A more continuous dimension is the good-poor dimension that describes how well the patient functioned before the active phase onset. These adjustment are useful in predicting prognosis as individuals with poor-premorbid schizophrenia are more likely to have long hospitalizations, and more likely to require re-hospitalization compared with good-premorbid patients.[5]

Type I and Type II.

Course of illness

Individuals differ in symptom intensity and presentation over time. Schizophrenia is considered a chronic, relapsing disorder since patients will experience residual symptoms after an active period, and cycle between the two.

Prodromal

The prodromal phase is a gradual deterioration of functioning, marked by strange behaviour and social isolation. This is before any clear psychotic symptoms appear, and may last for years or days before developing into full blown, active schizophrenia.

Active

The active phase is marked by prominent psychotic symptoms.

Residual

The residual phase occurs after an active period, and individuals will continue to experiences cognitive, behavioral, and social dysfunctions but not as strongly as during a psychotic episode.

Epidemiology

The incidence of schizophrenia varies with a median of 15.2 per 100,000, with males more likely than females to develop schizophrenia at a ratio of 1.4 to 1. Individuals who immigrate have a median risk ratio of 4.6 compared to individuals born in that country. Individuals living in urban areas have a higher risk than those in mixed urban/rural sites.[6] The prevalence of schizophrenia does not significantly differ between males and females, or between urban, rural, and mixed sites. Migrants have a higher prevalence of schizophrenia compared to native-born individuals with a 1.8:1 ratio. Economically, prevalence estimates in emerging and developed countries are higher than in less developed countries.[7]

Causes

The exact cause of schizophrenia is unknown, but several biochemical and structural abnormalities have been found and remain the focus for research and treatment. Antipsychotic medication may produce cognitive deficits, so researchers are challenged to differentiate between the illness and drug side-effects, as well as co-morbid mental disorders and illicit drug use.

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, that is, schizophrenia may be due to a dopaminergic dysregulation, is based on several lines of evidence. First, individuals with Parkinson's disease are treated with dopamine precursors, most commonly L-dopa, which allow the brain to synthesize additional dopamine. Some patients begin to display similar to schizophrenia as a side-effect to the drug, which presumably produce abnormally high levels of dopamine. Also, antipsychotic drugs can produce Parkinsonian side effects by lowering dopamine function. Secondly, amphetamines can induce temporary psychosis and behaviors similar to schizophrenia in otherwise healthy individuals, and it also worsens symptom severity in patients with schizophrenia. A serendipitous discovery occurred in the 1950s when physicians found that chlorpromazine, a drug used previously for a different purpose, reduced the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Chlorpromazine is a member of the phenothiazine class of drugs used to treat schizophrenia, and exerts its action by blocking dopamine receptors, thus reducing the effects of dopamine. This evidence may reflect abnormalities not with dopamine itself, but rather with the systems with which it interacts: the the fronto-striato-pallido-thalamic loops, and the limbic structures, such as amygdala and hippocampus.[8]

A second biochemical area of research concerns the neurotransmitter glutamate and NMDA receptors. Postmortem examinations have found abnormally low levels of NMDA recpetors, and dysfunctions within subunits. This suggest an impairment of glutamate binding both within and projecting out from the hippocampus.[9] Drugs that block NMDA receptors, such as ketamine, mimic the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and provide further evidence of glutamate dysfunction.[10]

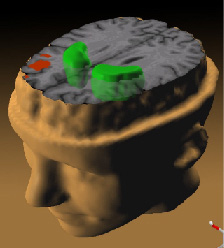

Positron emission topography studies have found a loss of grey matter. Other neuro-imaging studies have found decreased neuron activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which may explain the cognitive deficits in attention and planning not caused by antipsychotic treatment.[11]

Treatment

References

- ↑ From the Greek, schiz - to split, and phren - mind

- ↑ Andreasen NC, Olsen S (1982). "Negative v positive schizophrenia. Definition and validation". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39 (7): 789–94. PMID 7165478. [e]

- ↑ Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987). "The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia". Schizophr Bull 13 (2): 261–76. PMID 3616518. [e]

- ↑ Fenton WS, McGlashan TH (1991). "Natural history of schizophrenia subtypes. I. Longitudinal study of paranoid, hebephrenic, and undifferentiated schizophrenia". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 48 (11): 969–77. PMID 1747020. [e]

- ↑ Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al (1999). "Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56 (3): 241–7. PMID 10078501. [e]

- ↑ McGrath J, Saha S, Welham J, El Saadi O, MacCauley C, Chant D (2004). "A systematic review of the incidence of schizophrenia: the distribution of rates and the influence of sex, urbanicity, migrant status and methodology". BMC Med 2: 13. DOI:10.1186/1741-7015-2-13. PMID 15115547. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J (2005). "A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia". PLoS Med. 2 (5): e141. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141. PMID 15916472. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Willner P (1997). "The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: current status, future prospects". Int Clin Psychopharmacol 12 (6): 297–308. PMID 9547131. [e]

- ↑ Gao XM, Sakai K, Roberts RC, Conley RR, Dean B, Tamminga CA (2000). "Ionotropic glutamate receptors and expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits in subregions of human hippocampus: effects of schizophrenia". Am J Psychiatry 157 (7): 1141–9. PMID 10873924. [e]

- ↑ Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. (2001). Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(4), 455–67. PMID 11557159

- ↑ Berman KF, Zec RF, Weinberger DR (1986). "Physiologic dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. II. Role of neuroleptic treatment, attention, and mental effort". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 43 (2): 126–35. PMID 2868701. [e]