User:Milton Beychok/Sandbox

Liquefied natural gas or LNG is natural gas (predominantly methane, CH4) that has been converted into liquid form for ease of transport and storage. More simply put, it is the liquid form of the natural gas that people use in their homes for cooking and for heating,

A typical raw natural gas contains only about 80% methane and a number of higher boiling hydrocarbons as well as a number of impurities. Before it is liquefied, it is typically purified so as to remove the higher-boiling hydrocarbons and the impurities. The resultant liquefied natural gas contains about 95% or more methane and it is a clear, colorless and essentially odorless liquid which is neither corrosive nor toxic.[1][2]

LNG occupies only a very small fraction (1/600th) of the volume of natural gas and is therefore more economical to transport across large distances. It can also be stored in large quantities that would be impractical for storage as a gas.[1][2]

Process description for the production of LNG

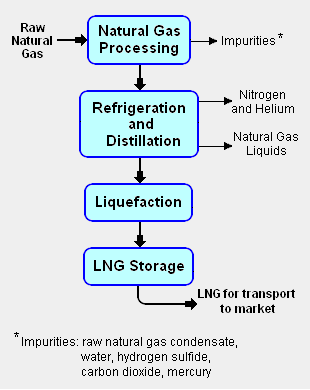

The liquefaction process involves separating the raw natural gas from any associated water and high-boiling hydrocarbon liquids (referred to as natural gas condensate) that may be associated with the raw gas. The raw gas is then further purified in a natural gas processing plant to remove remove impurities such as the acid gases hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and carbon dioxide (CO2), any residual water liquid or vapor, mercury, nitrogen and helium which could cause difficulty downstream. ( See the block flow diagram of the liquefaction process in Fig.1)

The purified natural gas is next refrigerated and distilled to recover ethane (C2H6), propane (C3H8), butanes (C4H10) and any higher boiling hydrocarbons, collectively referred to as natural gas liquids (NGL). The natural gas is then condensed into a liquid at essentially atmospheric pressure by using further refrigeration to cool it to approximately -162 °C (260 °F).

As mentioned above, the reduction in volume makes LNG much more cost efficient to transport over long distances where pipelines do not exist. Where transporting natural gas by pipelines is not possible or economical, it can be transported by specially designed cryogenic sea vessels called LNG carriers or by either cryogenic rail or road tankers.

History

Natural gas liquefaction dates back to the 1820s when British physicist Michael Faraday experimented with liquefying different types of gases. German engineer Carl Von Linde built the first practical vapor-compression refrigeration system in the 1870s.

The first commercial LNG liquefaction plant was built in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1941 and the LNG was stored in tanks at atmospheric pressure, which raised the possibility that LNG could be transported in sea-going vessels. In January 1959, the world's first LNG carrier, a converted freighter named The Methane Pioneer, containing five small, insulated aluminum tanks transported 5,000 m3 of LNG from Lake Charles, Louisiana in the United States to Canvey Island in England's Thames river. That voyage demonstrated that LNG could be transported safely across the oceans. During the next 14 months, that same freighter delivered seven additional cargoes with only a few small problems.[2][3]

Over the next 14 months, seven additional cargoes were delivered with only minor problems.

Following the successful performance of The Methane Pioneer, the British Gas Council proceeded with plans to implement a commercial project to import LNG from Venezuela to Canvey Island. However, before the commercial agreements could be finalized, large quantities of natural gas were discovered in Libya and in the gigantic Hassi R' Mel field in Algeria, which are only half the distance to England as Venezuela. With the start-up of the 260 million cubic feet per day (MMcfd) Arzew GL4Z or Camel plant in 1964, the United Kingdom became the world's first LNG importer and Algeria the first LNG exporter. Algeria has since become a major world supplier of natural gas as LNG.

After the concept was shown to work in the United Kingdom, additional liquefaction plants and import terminals were constructed in both the Atlantic and Pacific regions. Four marine terminals were built in the United States between 1971 and 1980. They are in Lake Charles (operated by CMS Energy), Everett, Massachusetts (operated by SUEZ through their Distrigas subsidiary), Elba Island, Georgia (operated by El Paso Energy), and Cove Point, Maryland (operated by Dominion Energy). After reaching a peak receipt volume of 253 BCF (billion cubic feet) in 1979, which represented 1.3 percent of U.S. gas demand, LNG imports declined because a gas surplus developed in North America and price disputes occurred with Algeria, the sole LNG provider to the U.S. at that time. The Elba Island and Cove Point receiving terminals were subsequently mothballed in 1980 and the Lake Charles and the Everett terminals suffered from very low utilization.

The first exports of LNG from the U.S. to Asia occurred in 1969 when Alaskan LNG was sent to Japan. Alaskan LNG is derived from natural gas that is produced by ConocoPhillips and Marathon from fields in Cook Inlet in the southern portion of the state of Alaska, liquefied at the Kenai Peninsula LNG plant (one of the oldest, continuously operated LNG plants in the world) and shipped to Japan. The LNG market in both Europe and Asia continued to grow rapidly from that point on. The figure below shows worldwide growth in LNG since 1970.

LNG transportation

Location of LNG facilities

Some Statistics

Conversion tables

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Frequently Asked Questions About LNG From the website of the California Energy Commission

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Introduction To LNG Michelle Michot Foss (January 2007), Center for Energy Economics (CEE), Bureau of Economic Geology, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas

- ↑ Michael R. Tusiani and Gordon Shearer (2007). LNG: A Nontechnical Guide, p.138. ISBN 0-87814-885-X.