Tet Offensive

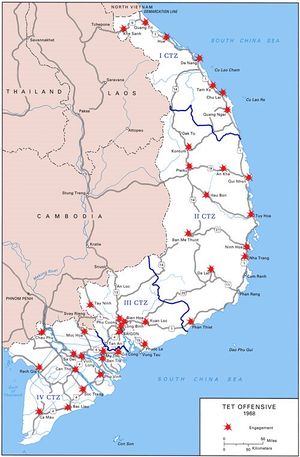

On January 31, 1968, during the traditional cease-fire of the Tet holiday, Commuist forces attacked 36 of 44 provincial capitals and 5 of 6 major cities. The North Vietnamese called it Tet Mau Than or Tong Kong Kich/Tong Kong Ngia (TCK/TCN, General Offensive/Uprising) [1] It is unclear to which the Battle of Khe Sanh was part of an overall strategy to draw American forces away from the cities. Some agencies did not expect it, while others had suspected an oncoming offensive.

At the Central Intelligence Agency, Undersecretary of State Nicholas deB. Katzenbach and Assistant Secretary of State Philip Habib were being briefed about a suspected offensive, probably at the end of Tet, when the word of the first attacks came. [2]

North Vietnamese planners hoped to incite a popular uprising. [3] However, the Tet Offensive had a devastating impact on Johnson's political position in the U.S., and in that sense was a strategic victory for the Communists. [4]

Warning

In U.S. intelligence, three components appeared to have predicted the Tet action:[5]

- the Army communications intelligence group supporting MG Frederick C. Weyand's 3rd Corps[6]

- National Security Agency, although it did not recognize the scope of the offensive[7]

- CIA's Saigon Station

These failed, however, to make much impression outside the areas tactically concerned. Indeed, they were being delivered in a context where senior officials did not want to hear contradictory information; In September 1967, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Walt Rostow said that told the Agency that because President Lyndon Baines Johnson wanted some "useful intelligence on Vietnam for a change," the CIA should prepare a list of positive (only) developments in the war effort, which Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms sent to Rostow with a dissenting cover note that Rostow removed. but Rostow pulled off that cover note and so was finally able to give the President a "good news" study from the CIA.[8]

Hue

The harshest fighting came in the old imperial capital of Hue. The city fell to the PAVN, which immediately set out to identify and execute thousands of government supporters among the civilian population. The allies fought back with all the firepower at their command. House to house fighting recaptured Hue on February 24. In Hue, five thousand enemy bodies were recovered, with 216 U.S. dead, and 384 ARVN fatalities. A number of civilians had been executed while the PAVN held the city.

Nationwide, the enemy lost tens of thousands killed, US lost 1,100 dead, ARVN 2,300. The people of South Vietnam did not rise up. Pacification, however, suspended in half the country, and a half million more people became refugees.

Media events

They avoided American strongholds and targeted GVN government offices and ARVN installations, other than "media opportunities" such as attempting to a fight, by a small but determined squad, of the U.S. Embassy. [9]

References

- ↑ Hanyok, Robert J. (2002), Chapter 7 - A Springtime of Trumpets: SIGINT and the Tet Offensive, Spartans in Darkness: American SIGINT and the Indochina War, 1945-1975, Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency, p. 310

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don (2001), Tet! The Turning Point in the Vietnam War, JHU Press,pp. 18-20

- ↑ Adams, Sam (1994), War of Numbers: An Intelligence Memoir, Steerforth Press

- ↑ Willbanks, James H. (2006), The Tet Offensive: A Concise History

- ↑ Ford, Harold R. (1997), Episode 3 1967-1968: CIA, the Order-of-Battle Controversy, and the Tet Offensive, CIA and the Vietnam Policymakers: Three Episodes 1962 - 1968, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, Ford Episode 3

- ↑ Ford Episode 3, General Weyand, to author, 17 April 1991. Weyand's communications intelligence battalion comander, LTC Norman Campbell, supports Weyand's accounts.

- ↑ Hanyok, pp. 326-333

- ↑ George Allen, The Indochina Wars, cited in Ford Episode 3

- ↑ Oberdorfer, pp. 2-14