Poverty and obesity

For the course duration, the article is closed to outside editing. Of course you can always leave comments on the discussion page. The anticipated date of course completion is 01 April 2012. One month after that date at the latest, this notice shall be removed. Besides, many other Citizendium articles welcome your collaboration! |

Introduction

Poverty and obesity are very closely linked. In the USA, the highest rates of obesity occur in the poorest population groups. Poverty is associated with lower expenditure on food, and low consumption of fruit and vegetables, and energy-dense foods represent the lowest-cost option for consumers. However, the high energy density and palatability of sweets and fats are associated with higher energy intakes. [1]

Diet Quality

The Relationship Between Diet Quality and Socio-Economic Status

People of higher socio-economic status (SES) tend to have better quality diets.

What is a good quality diet? What is a bad quality diet? Why is a bad quality diet detrimental to general health? Link to title: obesity is associated with poor diet quality and therefore low SES (or poverty).

[Figure: a food pyramid detailing what a good quality diet should consist of and in what quantities.]

Extra points: 1) Variables to consider – country, ethnic origin, type of SES indicator; and age, sex, occupation, education, income levels. 2) The difference between poverty and low SES? Poverty is more intense…

Evidence for Socio-Economic Status Affecting Diet Quality

Components of the diet: whole grains/refined cereals, fruit and vegetables, milk, lean meat and fish/fatty meat, added fats, sugars, sweetened beverages, fibre and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), macronutrients (protein, carbohydrate, sucrose, types of fat).

Data selected from studies focussing on one dietary component in high/low income families to compare diet quality to SES.

Causation of Poor Diet Quality in People of Low Socio-Economic Status

Food prices and diet costs, food access and the food environment, education and culture.

Link to energy density and energy cost: in general, low SES causes people to select food of low cost, and these foods tend to be energy dense.

Helen Golz 18:37, 25 October 2011 (UTC)

Dietary Energy Density

Influence on energy intakes

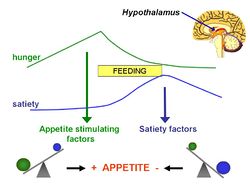

Energy dense foods have been shown to result in higher energy intakes overall. It has been found that upon eating any given meal under laboratory conditions, participants consume a constant volume. Therefore, the calorie intake is determined by the energy density of the food eaten. In addition to this, palatable, energy dense foods have also been linked to an attenuation of satiety and ‘passive consumption’, thus resulting in a greater energy intake [2]. Foods with a low energy density, however, give a lasting feeling of satiety and fullness. This effect results in a lower consumption of energy during the meal, and for the rest of that day [3]. Previous literature has postulated that the effect of energy density of foods on energy intake is due to poor human ability to distinguish between high and low energy dense foods. Therefore we do not accommodate for this in our eating habits, thus fail to maintain energy balance [4].

Function of water content

The energy density of foods (MJ/kg) is determined by their water content, whereby energy dilute foods are well hydrated, and energy dense foods are comparably dry. Energy dense foods may also contain fat, sugar and starch, and include foodstuffs such a s crisps, with an energy density of 23MJ/kg and chocolate (22MJ/kg). Examples of foods with a low energy density are fruits and vegetables [5].

Palatability of energy dense foods

Energy-dense foods tend to be more palatable and pleasurable to eat than foods with a low energy density. Animal studies have shown that sugar and fat stimulate reward centres in brain, resulting in taste preference. It has been proposed that humans, and other animals, developed a taste preference for energy dense foods in order to promote their survival in an environment where food can be scarce and unreliable[6]. Conversely, it has also been suggested that human taste preference for energy dense foods is acquired during early life from their environment. This preference can be developed through repeated exposure, an association with the metabolic consequences, or parental influence[7]. Hannah Harman 09:35, 27 October 2011 (UTC)

Energy Costs

The Relationship Between Energy Density and Energy Cost

There is an apparent inverse relationship between the energy density of foods and the energy cost of food. This meaning that energy dense foods are cheaper for food consumption then the 'healthier' less energy dense food substances.

Its is observed that diets which are high in fats, sugars and grains are associated with lower diet costs and are an effective way of saving money but still satisfying the need for food.

French studies have shown that for every additional 100g of sweets and fats there was a 0.05 - 0.40 Euro per day reduction in the cost of diet in contrast to each 100g additional portion of fruit and vegetables there was a 0.18 - 0.29 Euro per day increase in dietary costs.

Studies have also shown evidence that in America obesity is an economic issue, rather than a medical, education or genetic issue.

Pricing of Foods and Influence of Income/SES

It is well known that fats and sugars at a very low cost provide dietary energy. Therefore price reduction studies were carried out on alternative foods to investigate whether a reduction in price would see an increase in the consumption of foods such as lower fat foods and fresh fruits.

Other studies carried out include those where an increase on high sugar/fat foods price caused a reduction in consumption. This can then be further enhanced into a larger context and if taxes were applied to such foods would we see any significant change in BMI or obesity prevalence across the population. We may see a reduction in the consumption but does this directly relate to a decrease in weight?

Thus

Are the economic constraints contributing to the unhealthy food choices made by the communities in the lower SES in the developed worlds of today?

References

- ↑ Drewnowski A, Specter SE (2004) Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs Am J Clin Nutr 79:6-16 PMID 14684391

- ↑ Prentice A, Poppit S (1996) Importance of energy density and macronutrients in the regulation of energy intake. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, 20, 18-23

- ↑ Rolls B et al (1998) Volume of foods consumed affects satiety in men. Am J Clin Nutr , 67, 1170–7

- ↑ Prentice, A, Jebb, S (2003) Fast foods, energy density and obesity: a possible mechanistic link. Obesity Reviews, 4, 187-194. PMID 14649369

- ↑ Drewnowski A (1998) Energy density, palatability, and satiety: implications for weight control. Nutr Rev, 56, 347–53

- ↑ Drewnowski A, Specter S (2004) Poverty and obesity:the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr, 79, 6-16

- ↑ Birch L (1999) Development of food preferences. Annu Rev Nutr, 19, 41–62