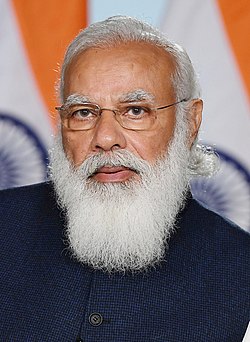

Narendra Modi

Narendra Modi (born 17 September 1950) is an Indian politician who has served as the Prime Minister of India since 26 May 2014 (and is still in office as of July 2024). Modi was the chief minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014 and is the Member of Parliament (MP) for Varanasi. He is a member of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a right wing Hindu nationalist paramilitary volunteer organization. His full name is Narendra Damodardas Modi.

Early life and education

Narendra Damodardas Modi was born on 17 September 1950 to a Gujarati Hindu family of oil presser (Modh-Ghanchi) in Vadnagar, Mehsana district, Bombay State (present-day Gujarat). He was the third of six children born to Damodardas Mulchand Modi (c. 1915–1989) and Hiraben Modi (1923–2022).

Modi had infrequently worked as a child in his father's tea business on the Vadnagar railway station platform, according to Modi and his neighbors.

Modi completed his higher secondary education in Vadnagar in 1967; his teachers described him as an average student and a keen, gifted debater with an interest in theater. He preferred playing larger-than-life characters in theatrical productions, which has influenced his political image.

When Modi was eight years old, he was introduced to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and began attending its local shakhas (training sessions). There, he met Lakshmanrao Inamdar, who inducted Modi as a balswayamsevak (junior cadet) in the RSS and became his political mentor. While Modi was training with the RSS, he also met Vasant Gajendragadkar and Nathalal Jaghda, Bharatiya Jana Sangh leaders who in 1980 helped found the BJP's Gujarat unit. As a teenager, he was enrolled in the National Cadet Corps.

In a custom traditional to Narendra Modi's caste, his family arranged a betrothal to Jashodaben Chimanlal Modi, leading to their marriage when she was 17 and he was 18. Soon afterwards, he abandoned his wife, and left home. The couple never divorced but the marriage was not in his public pronouncements for many decades. In April 2014, shortly before the national election in which he gained power, Modi publicly affirmed he was married and that his spouse was Jashodaben. The marriage was unconsummated and Modi kept it secret because he would not have been able to become a pracharak in the puritanical RSS.

Modi spent the following two years traveling across northern and northeastern India. In interviews, he has described visiting Hindu ashrams founded by Swami Vivekananda: the Belur Math near Kolkata, the Advaita Ashrama in Almora, and the Ramakrishna Mission in Rajkot.

In mid 1968, Modi reached Belur Math but was turned away, after which he visited Calcutta, West Bengal, and Assam, stopping in Siliguri and Guwahati. He then went to the Ramakrishna Ashram in Almora, where he was again rejected, before returning to Gujarat via Delhi and Rajasthan in 1968 to 1969. In either late 1969 or early 1970, he returned to Vadnagar for a brief visit before leaving again for Ahmedabad, where he lived with his uncle and worked in his uncle's canteen at Gujarat State Road Transport Corporation.

In Ahmedabad, Modi renewed his acquaintance with Inamdar, who was based at the Hedgewar Bhavan (RSS headquarters) in the city. Modi's first-known political activity as an adult was in 1971 when he joined a Jana Sangh Satyagraha in Delhi led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee to enlist to fight in the Bangladesh Liberation War. The Indira Gandhi-led central government prohibited open support for the Mukti Bahini; according to Modi, he was briefly held in Tihar Jail. After the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, Modi left his uncle's employment and became a full-time pracharak (campaigner) for the RSS, working under Inamdar.[1] Shortly before the war, Modi took part in a non-violent protest in New Delhi against the Indian government, for which he was arrested.

In 1978, Modi received a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree in political science from the School of Open Learning at the Delhi University. In 1983, he received a Master of Arts (MA) degree in political science from Gujarat University, graduating with a first class as an external distance learning student.

Early political career

In June 1975, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency in India that lasted until 1977. During this period, known as "the Emergency", many of her political opponents were jailed and opposition groups were banned. Modi was appointed general secretary of the "Gujarat Lok Sangharsh Samiti", an RSS committee coordinating opposition to the Emergency in Gujarat. Shortly afterwards, the RSS was banned. Modi was forced to go underground in Gujarat and frequently traveled in disguise to avoid arrest. He became involved in the printing of pamphlets opposing the government, sending them to Delhi and organizing demonstrations. He was also involved with creating a network of safe houses for individuals who were wanted by the government, and in raising funds for political refugees and activists. During this period, Modi wrote a Gujarati-language book titled Sangharsh Ma Gujarat (In the Struggles of Gujarat), which describes events during the Emergency. While in this role, Modi met trade unionist and socialist activist George Fernandes and several other national political figures.

Modi became an RSS sambhag pracharak (regional organiser) in 1978, overseeing activities in Surat and Vadodara, and in 1979, he went to work for the RSS in Delhi, where he researched and wrote the RSS's history of the Emergency. Shortly after, he returned to Gujarat and in 1985, the RSS assigned him to the BJP. In 1987, Modi helped organize the BJP's campaign in the Ahmedabad municipal election, which the party won comfortably; according to biographers, Modi's planning was responsible for the win.[2] After L. K. Advani became president of the BJP in 1986, the RSS decided to place its members in important positions within the party; Modi's work during the Ahmedabad election led to his selection for this role. Modi was elected organizing secretary of the BJP's Gujarat unit later in 1987.

Modi rose within the party and was named a member of its National Election Committee in 1990. Modi took a brief break from politics in 1992. Modi returned to electoral politics in 1994, partly at the insistence of Advani; as party secretary, Modi's electoral strategy was considered central to the BJP victory in the 1995 state assembly election. In November of that year, Modi was appointed BJP national secretary and transferred to New Delhi, where he assumed responsibility for party activities in Haryana and Himachal Pradesh. The following year, Shankersinh Vaghela, a prominent BJP leader from Gujarat, defected to the Indian National Congress after losing his parliamentary seat in the Lok Sabha election. Modi, who was on the selection committee for the 1998 Gujarat Legislative Assembly election, favored supporters of BJP leader Keshubhai Patel over those supporting Vaghela to end factional division in the party. His strategy was credited as central to the BJP winning an overall majority in the 1998 election, and Modi was promoted to BJP general secretary in May of that year.

Chief Minister of Gujarat (2001–2014)

In 2001, Keshubhai Patel's health was failing and the BJP lost a few state assembly seats in by-elections. Allegations of abuse of power, corruption. and poor administration were made, and Patel's standing had been damaged by his administration's handling of the earthquake in Bhuj in 2001. The BJP national leadership sought a new candidate for the chief ministership of Gujarat State, and Modi, who had expressed misgivings about Patel's administration, was chosen as a replacement. Modi declined an offer to become Patel's deputy chief minister, stating he was "going to be fully responsible for Gujarat or not at all". On 3 October 2001, Modi replaced Patel as Chief Minister of Gujarat with the responsibility of preparing the BJP for the upcoming December 2002 election. On 7 October, Modi was sworn in, and he entered the Gujarat state legislature on 24 February 2002.

2002 Gujarat riots

On 27 February 2002, a train with several hundred passengers burned near Godhra, killing approximately 60 people. The train carried a large number of Hindu pilgrims who were returning from Ayodhya after a religious ceremony at the site of the demolished Babri Masjid. In a public statement, Gujarat Chief Minister Modi said local Muslims were responsible for the incident. The next day, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad called for a bandh (general strike) across the state. Riots began during the bandh, and anti-Muslim violence spread through Gujarat. The government's decision to move the bodies of the train victims from Godhra to Ahmedabad further inflamed the violence. The state government later stated 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus were killed during the riots; independent sources put the death toll at over 2,000, the vast majority of them Muslims. Approximately 150,000 people were driven to refugee camps. Numerous women and children were among the victims; the violence included mass rapes and mutilation of women.[3]

Scholars consider the Government of Gujarat to have been complicit in the riots, and it has received much criticism for its handling of the situation; some scholars explicitly blame Modi.The Modi government imposed a curfew in 26 major cities, issued shoot-at-sight orders, and called for the army to patrol the streets; these measures failed to prevent the violence from escalating. The president of the state unit of the BJP expressed support for the bandh despite such actions being illegal at the time. State officials later prevented riot victims from leaving the refugee camps, which were often unable to meet the needs of those living there. Muslim victims of the riots were subjected to further discrimination when the state government announced their compensation would be half that offered to Hindu victims; this decision was later reversed after the issue was taken to court. During the riots, police officers often did not intervene in situations where they were able. Several scholars have described the violence as a pogrom and others have called it an example of state terrorism.

Modi's personal involvement in the 2002 events has continued to be debated. During the riots, he said, "What is happening is a chain of action and reaction". Later in 2002, Modi said the way in which he had handled the media was his only regret regarding the episode.[4] In March 2008, the Supreme Court of India reopened several cases related to the riots, including that of the Gulbarg Society massacre, and established a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to look into the issue. In response to a petition from Zakia Jafri, the widow of Ehsan Jafri, who was killed in the Gulbarg Society massacre, in April 2009, the court also asked the SIT to investigate Modi's complicity in the killings. The SIT questioned Modi in March 2010; in May, it presented to the court a report finding no evidence against him. In July 2011, the court-appointed amicus curiae Raju Ramachandran submitted his final report to the court. Contrary to the SIT's position, Ramachandran said Modi could be prosecuted based on the available evidence. The Supreme Court sent the matter to the magistrate's court. The SIT examined Ramachandran's report, and in March 2012 submitted its final report, asking for the case to be closed. Zakia Jafri filed a protest petition in response. In December 2013, the magistrate's court rejected the protest petition, accepting the SIT's finding there was no evidence against Modi. In 2022, the Supreme Court dismissed a petition by Zakia Jafri in which she challenged the exoneration given to Modi in the riots by the SIT, and upheld previous rulings that no evidence against him was found.

Later terms as Chief Minister of Gujurat

Following the 2002 violence, calls for Modi to resign as chief minister were made from politicians within and outside the state, including leaders of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and the Telugu Desam Party—partners in the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance coalition—and opposition parties stalled Parliament over the issue. Modi submitted his resignation at the April 2002 BJP national executive meeting in Goa, but it was not accepted. Despite opposition from the election commissioner, who said a number of voters were still displaced, Modi succeeded in advancing the election to December 2002. Modi made significant use of anti-Muslim rhetoric during his campaign, and the BJP profited from religious polarization among voters.[5] On 22 December 2002, Modi was sworn in for a second term.

During Modi's second term, the government's rhetoric shifted from Hindutva to Gujarat's economic development. He curtailed the influence of Sangh Parivar organizations such as Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS) and Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP). When the BKS staged a farmers' demonstration, Modi ordered the BKS's eviction from state-provided houses, and his decision to demolish 200 illegal temples in Gandhinagar deepened the rift with the VHP. Modi retained connections with some Hindu nationalists.

Modi's relationship with Muslims continued to attract criticism. Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee distanced himself, reaching out to North Indian Muslims before the 2004 Indian general election, following which, Vajpayee called the violence in Gujarat a reason for the BJP's electoral defeat and said it had been a mistake to leave Modi in office after the riots. Western nations also raised questions about Modi's relationship with Muslims: the U.S. State Department barred him from entering the United States in accordance with the recommendations of that country's Commission on International Religious Freedom, the only person to be denied a U.S. visa under this law.[6] The U.K. and the European Union (E.U.) refused to admit Modi because of what they saw as his role in the 2002 riots. As Modi rose to prominence in India, the U.K. and the E.U. lifted their bans in October 2012 and March 2013, respectively, and after his election as prime minister in 2014, the U.S. lifted its ban and invited him to Washington, D.C.

During the runup to the 2007 Gujarat Legislative Assembly election and the 2009 Indian general election, the BJP intensified its rhetoric on terrorism. Modi criticized Prime Minister Manmohan Singh "for his reluctance to revive anti-terror legislation" such as the 2002 Prevention of Terrorism Act.

Despite the BJP's shift away from explicit Hindutva, Modi's campaigns in 2007 and 2012 Gujarat Legislative Assembly elections contained elements of Hindu nationalism. He attended only Hindu religious ceremonies and had prominent associations with Hindu religious leaders. During his 2012 campaign, Modi twice refused to wear skullcap gifted by Muslim leaders. He did, however, maintain relations with Dawoodi Bohra. Modi's 2012 campaign included references to issues known to cause religious polarization, including Afzal Guru and the death of Sohrabuddin Sheikh. The BJP did not nominate any Muslim candidates for the 2012 assembly election.[7] During the 2012 campaign, Modi attempted to identify himself with the state of Gujarat, a strategy similar to that used by Indira Gandhi during the Emergency, and projected himself as protecting Gujarat against persecution by the rest of India. While campaigning for the 2012 Gujarat Legislative Assembly election, Modi made extensive use of holograms and other technologies, allowing him to reach a large number of people, something he repeated in the 2014 general election.

Attribution

- Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Wikipedia.

References

- ↑ Mukhopadhyay, Nilanjan (2013). Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times. Westland. ISBN 9-789-383-26048-5. OCLC 837527591.

- ↑ Shekhar, Himanshu (2015). Management Guru Narendra Modi. Diamond Pocket Books Pvt Ltd. p. 64. ISBN 978-81-288-2803-4.

- ↑ Filkins, Dexter (2 December 2019). "Blood and Soil in Narendra Modi's India". The New Yorker. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ↑ Barry, Ellen (7 April 2014). "Wish for Change Animates Voters in India Election". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ↑ Jaffrelot, Christophe (2015). "Narendra Modi and the Power of Television in Gujarat". Television & New Media 16(4): 346–353. doi:10.1177/1527476415575499. S2CID 145758627.

- ↑ Mann, James (2 May 2014). "Why Narendra Modi Was Banned From the U.S." The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ↑ Jaffrelot, Christophe (9 May 2016). "Narendra Modi Between Hindutva and Subnationalism: The Gujarati Asmita of a Hindu Hriday Samrat". India Review 15(2): 196–217. doi:10.1080/14736489.2016.1165557. S2CID 156137272. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.