Ireland (state)

Template:Infobox Country or territory Ireland (Template:Lang-ga) (IPA [ˈeːrʲə]) is a country in north-western Europe. The modern sovereign state occupies five-sixths of the island of Ireland, which was partitioned in 1921. The term Republic of Ireland is "the description of the State"[1]. It is bordered by Northern Ireland (part of the United Kingdom) to the north, by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and by the Irish Sea to the east. It is a member of the European Union, has a developed economy and a population of 4.2 million.[2]

Name

Bunreacht na hÉireann, the constitution of Ireland, provides that "the name of the state is Éire, or, in the English language, "Ireland". The state is also described as the "Republic of Ireland," in order to distinguish it from the island of Ireland and from Northern Ireland. The Republic of Ireland Act defined Republic of Ireland as the description of the state in 1949 (the purpose of the act being to declare that the state was a republic rather than a form of constitutional monarchy). However, because this was a statutory provision, the constitutional name of "Ireland" remains the official name of the state, whilst "Republic of Ireland" is a description of the state. "Republic of Ireland" is also the accepted legal name of the state in the United Kingdom as per the Ireland Act 1949. Therefore it is the name Ireland that is used for official purposes such as treaties, government and legal documents, and membership of international organisations. However with Irish being named the European Union's twenty-first official language in 2007; the state will be referred to in both constitutional official languages, the Irish and English languages, similarly to other countries such as Finland and Belgium using more than one language at EU level. This means the label 'Éire Ireland' will be used on various signage and nameplates referring to the state.[3]

The state is also known by other names in English, such as Éire, The Free State and the Twenty-six Counties. The use of Éire when speaking English in Ireland has become increasingly rare.Template:Fact Often in the United Kingdom the state is referred to as Southern Ireland, though this term is used informally and was only used officially for a brief period in Irish history. Irish people sometimes refer to the state as "The South" - it is not uncommon to hear Northern Irish people talking about going "down south".

The state has had more than one official title. The revolutionary state, declared in 1919 by the large majority of Irish Members of (the United Kingdom) Parliament elected in 1918, was known as the "Irish Republic"; when the state achieved de jure independence in 1922, it became known as the "Irish Free State" (in the Irish language Saorstát Éireann), a name that was retained until 1937.

History

The state known today as the Republic of Ireland came into being when 26 of the counties of Ireland seceded from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) in 1922. The remaining six counties remained within the UK as Northern Ireland. This action, known as the Partition of Ireland, came about because of complex constitutional developments in the early twentieth century.

From 1 January 1801 until 6 December 1922, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. During the Great Famine from 1845 to 1849 the island's population of over 8 million fell by 30 percent. One million Irish died of starvation and another 1.5 million emigrated, (see: Mokyr, Joel (1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History 1700-1850". Irish Economic and Social History xi: 101-121. ) which set the pattern of emigration for the century to come and would result in a constant decline up to the 1960s. From 1874, but particularly from 1880 under Charles Stewart Parnell, the Irish Parliamentary Party moved to prominence with its attempts to achieve Home Rule, which would have given all of Ireland some autonomy without requiring it to leave the United Kingdom. It seemed possible in 1911 when the House of Lords lost their veto, and John Redmond secured the Third Home Rule Act 1914. The unionist movement, however, had been growing since 1886 among Irish Protestants, fearing that they would face discrimination and lose economic and social privileges if Irish Catholics were to achieve real political power. Though Irish unionism existed throughout the whole of Ireland, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century unionism was particularly strong in parts of Ulster, where industrialisation was more common in contrast to the more agrarian rest of the island. (Any tariff barriers would, it was feared, most heavily hit that region.) In addition, the Protestant population was more strongly located in Ulster, with unionist majorities existing in about four counties. Under the leadership of the Dublin-born Sir Edward Carson and the northerner Sir James Craig they became more militant. In 1914, to avoid rebellion in Ulster, the British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, with agreement of the leadership of the Irish Party leadership, inserted a clause into the bill providing for home rule for 26 of the 32 counties, with an as of yet undecided new set of measures to be introduced for the area temporarily excluded. Though it received the Royal Assent, the Third Home Rule Act 1914's implementation was suspended until after the Great War. (The war at that stage was expected to be ended by 1915, not the four years it did ultimately last.) For the prior reasons of ensuring the implementation of the Act at the end of the war Redmond and his Irish National Volunteers supported the Allied cause, and tens of thousands joined battalions of the 10th and 16th (Irish) Divisions of the New British Army.

Template:History of Ireland In January 1919, after the December 1918 general elections, 73 of Ireland's 106 MPs elected were Sinn Féin members who refused to take their seats in the British House of Commons. Instead, they set up an extra-legal Irish parliament called Dáil Éireann. This Dáil in January 1919 issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence and proclaimed an Irish Republic. The Declaration was mainly a restatement of the 1916 Proclamation with the additional provision that Ireland was no longer a part of the United Kingdom. Despite this, the new Irish Republic remained unrecognised internationally except by Lenin's Russian Republic. Nevertheless the Republic's Aireacht (ministry) sent a delegation under Ceann Comhairle Sean T. O'Kelly to the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, but it was not admitted. After the bitterly fought War of Independence, representatives of the British government and the Irish rebels negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921 under which the British agreed to the establishment of an independent Irish State whereby the Irish Free State (in the Irish language Saorstát Éireann) with dominion status was created. The Dáil Éireann narrowly ratified the treaty.

The Treaty was not entirely satisfactory to either side. It gave more concessions to the Irish than the British had intended to give but did not go far enough to satisfy republican aspirations. The new Irish Free State was in theory to cover the entire island, subject to the proviso that six counties in the north-east, termed "Northern Ireland" (which had been created as a separate entity under the Government of Ireland Act 1920) could opt out and choose to remain part of the United Kingdom, which they duly did. The remaining twenty-six counties became the Irish Free State, a constitutional monarchy over which the British monarch reigned (from 1927 with the title King of Ireland). It had a Governor-General, a bicameral parliament, a cabinet called the "Executive Council" and a prime minister called the President of the Executive Council.

The Irish Civil War was the direct consequence of the creation of the Irish Free State. Anti-Treaty forces, led by Éamon de Valera, objected to the fact that acceptance of the Treaty abolished the Irish Republic of 1919 to which they had sworn loyalty, arguing in the face of public support for the settlement that the "people have no right to do wrong". They objected most to the fact that the state would remain part of the British Commonwealth and that Teachtaí Dála would have to swear an oath of fidelity to King George V and his successors. Pro-Treaty forces, led by Michael Collins, argued that the Treaty gave "not the ultimate freedom that all nations aspire to and develop, but the freedom to achieve it".

At the start of the war, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) split into two opposing camps: a pro-treaty IRA and an anti-treaty IRA. The pro-Treaty IRA became part of the new National Army. However, through the lack of an effective command structure in the anti-Treaty IRA, and their defensive tactics throughout the war, Collins and his pro-treaty forces were able to build up an army capable of overwhelming the anti-Treatyists. British supplies of artillery, aircraft, machine-guns and ammunition boosted pro-treaty forces, and the threat of a return of Crown forces to the Free State removed any doubts about the necessity of enforcing the treaty. The lack of public support for the anti-treaty Irregulars, and the determination of the government to overcome them, contributed significantly to their defeat.

The National Army suffered 800 fatalities and perhaps as many as 4,000 people were killed altogether. As their forces retreated, the Irregulars showed a major talent for destruction and the economy of the Free State suffered a hard blow in the earliest days of its existence.

On 29 December 1937, a new constitution, the Constitution of Ireland, came into force. It replaced the Irish Free State by a new state called simply "Ireland". Though this state's constitutional structures provided for a President of Ireland instead of a king, it was not technically a republic; the principal key role possessed by a head of state, that of symbolically representing the state internationally remained vested, in statute law, in the King as an organ.

The Irish state remained neutral during World War II.[4]

On 21 December 1948, the Republic of Ireland Act declared a republic, with the functions previously given to the Governor-General acting on the behalf of the King given instead to the President of Ireland.

The Irish state had remained a member of the then-British Commonwealth after independence until the declaration of a republic on 18 April 1949. Under Commonwealth rules declaration of a republic automatically terminated membership of the association; since a reapplication for membership was not made, Ireland consequently ceased to be a member.

The Republic of Ireland joined the United Nations in 1955 and the European Community (now the European Union) in 1973. Irish governments have sought the peaceful reunification of Ireland and have usually cooperated with the British government in the violent conflict involving many paramilitaries and the British Army in Northern Ireland known as "The Troubles". A peace settlement for Northern Ireland, the Belfast Agreement, was approved in 1998 in referenda north and south of the border, and is currently being implemented.

Politics

The state is a republic, with a parliamentary system of government. The President of Ireland, who serves as head of state, is elected for a seven-year term and can be re-elected only once. The president is largely a figurehead but can still carry out certain constitutional powers and functions, aided by the Council of State, an advisory body. The Taoiseach (prime minister), is appointed by the president on the nomination of parliament. The Taoiseach is normally the leader of the political party which wins the most seats in the national elections. It has become normal in the Republic for coalitions to form a government, and there has not been a single-party government since the period of 1987–1989.

The bicameral parliament, the Oireachtas, consists of a Senate, Seanad Éireann, and a lower house, Dáil Éireann. The Seanad is composed of sixty members; eleven nominated by the Taoiseach, six elected by two universities, and 43 elected by public representatives from panels of candidates established on a vocational basis. The Dáil has 166 members, Teachtaí Dála, elected to represent multi-seat constituencies under the system of proportional representation by means of the Single Transferable Vote. Under the constitution, parliamentary elections must be held at least every seven years, though a lower limit may be set by statute law. The current statutory maximum term is every five years.

The Government is constitutionally limited to fifteen members. No more than two members of the Government can be selected from the Senate, and the Taoiseach, Tánaiste (deputy prime minister) and Minister for Finance must be members of the Dáil. The current government consists of a coalition of two parties; Fianna Fáil under Taoiseach Bertie Ahern and the Progressive Democrats under Tánaiste Michael McDowell.

The main opposition in the current Dáil consists of Fine Gael and Labour. Smaller parties such as the Green Party, Sinn Féin and the Socialist Party also have representation in the Dáil.

Ireland joined the European Union in 1973 but has chosen to remain outside the Schengen Treaty. Citizens of the UK can freely enter Ireland without a passport thanks to the Common Travel Area.

Counties

The Republic of Ireland traditionally had twenty-six counties, and these are still used in cultural and sporting contexts. Dáil constituencies are required by statute to follow county boundaries, as far as possible. Hence counties with greater populations have multiple constituencies (e.g. Limerick East/West) and some constituencies consist of more than one county (e.g. Sligo-North Leitrim), but by and large, the actual county boundaries are not crossed.

As local government units, however, some have been restructured, with the now-abolished County Dublin distributed among three new county councils in the 1990s and County Tipperary having been administratively two separate counties since the 1890s, giving a present-day total of twenty-nine administrative counties and five cities. The five cities — Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Galway , and Waterford — are administered separately from the remainder of their respective counties. Five boroughs — Clonmel, Drogheda, Kilkenny, Sligo and Wexford — have a level of autonomy within the county:

| Map of the Republic of Ireland with numbered counties. | Republic of Ireland |

These counties are grouped together into regions for statistical purposes.

Geography

The island of Ireland extends over 84,421 km² or 32,556 mi², of which 83% (approx. five-sixths) belong to the Republic (70,280 km²; 27,103 mi²) and the remainder constituting Northern Ireland. It is bound to the west by the Atlantic Ocean, to the northeast by the North Channel. To the east is found the Irish Sea which reconnects to the ocean via the southwest with St George's Channel and the Celtic Sea. The west-coast of Ireland mostly consists of cliffs, hills and low mountains (the highest point being Carrauntoohil at 1,041 m or 3,414 ft). The interior of the country is relatively flat land, traversed by rivers such as the River Shannon and several large lakes or loughs. The centre of the country is part of the River Shannon watershed, containing large areas of bogland, used for peat extraction and production.

The local temperate climate is modified by the North Atlantic Current and is relatively mild. Summers are rarely very hot (temperatures only exceed 30ºC (86ºF) usually once every decade, though commonly reach 29ºC (84ºF) most summers, but it freezes only occasionally in winter (temperatures below -6ºC (21ºF) are uncommon). Precipitation is very common, with up to 275 days with rain in some parts of the country. Chief cities are the capital Dublin on the east coast, Cork in the south, Limerick, Galway on the west coast, and Waterford on the south east coast (see Cities in Ireland).

Education

- See also: Education in the Republic of Ireland

The education systems are largely under the direction of the government via the Minister for Education and Science (currently Mary Hanafin, TD). Recognised primary and secondary schools must adhere to the curriculum established by authorities that have power to set them.

The education systems in Ireland are complex due to a confusion of ownership, control and curricular assessment. This has arisen because the systems developed over long periods of time with variable influence by several key players, including the Irish state. Unlike in countries such as France, Ireland's state education system is largely limited to the content of the curriculum, although this too is mediated by voluntary interests.

Ownership Technically, the majority of Ireland's primary and secondary schools are owned by the Catholic parishes of the country. Parishes establish schools and this has tended to develop where the local Catholic Church provided the land under the ownership of a Board of Management, composed of various community interests, including but not exclusively so, the local Catholic priest. With the decline in numbers of priests, this has proven more and more problematic. The parish's school is then run by the Board of Management on behalf of the local community. With increasing numbers of non-Catholics in Ireland, the question of Catholic school ethos has become contested. The State provides and pays for the teachers, organises the curriculum and agrees to provide examinations and other centralised services for these schools. At second level, the system of ownership is more complex again because schools owned by the Churches, the State and other voluntary interests coexist side by side. At this level, the parish's interests are represented by a Board of Management / Trust established by an order of the Catholic Church under the direction of a Bishop. A state owned secondary school - generally called community or comprehensive schools - is wholly controlled by the State through the Department of Education and Science. A small number of other denominational schools exist such as those organised by the Islamic communities. The church ownership model extends to these groups too.

Control Control of schools is technically vested in the Catholic / Church of Ireland / church grouping. As the State decides the content of educational curricula with various interests, including the Churches, control is effectively in the State's purview. Ireland's educational systems can be characterised in a largely voluntary manner. This does not imply that their effects are politically neutral with class and other interests sequentially embedded throughout each system.

Economy

The economy of Ireland has transformed in recent years from an agricultural focus to one dependent on trade, industry and investment. Economic growth in Ireland averaged an exceptional 10% from 1995–2000, and 7% from 2001–2004. Industry, which accounts for 46% of GDP, about 80% of exports, and 29% of the labour force, now takes the place of agriculture as the country's leading sector.

Exports play a fundamental role in the state's robust growth, but the economy also benefits from the accompanying rise in consumer spending, construction, and business investment. On paper, the country is the largest exporter of software-related goods and services in the world. In fact, a lot of foreign software, and sometimes music, is filtered through the country to avail of the state's non-taxing of royalties from copyrighted goods.

A key part of economic policy, since 1987, has been Social Partnership which is a neo-corporatist set of voluntary 'pay pacts' between the Government, employers and trades unions. These usually set agreed pay rises for three-year periods.

The state joined in launching the euro currency system in January 1999 (leaving behind the Irish pound) along with ten other EU nations. The 1995 to 2000 period of high economic growth led many to call the country the Celtic Tiger. The economy felt the impact of the global economic slowdown in 2001, particularly in the high-tech export sector — the growth rate in that area was cut by nearly half. GDP growth continued to be relatively robust, with a rate of about 6% in 2001 and 2002. Growth for 2004 was over 4%, and for 2005 was 4.7%.

With high growth came high levels of inflation, particularly in the capital city. Prices in Dublin, where nearly 30% of Ireland's population lives, are considerably higher than elsewhere in the country Template:PDFlink, especially in the property market.

Ireland possesses the second highest GDP (PPP) per capita in the world (US$43,600 as of 2006), the fourth highest Human Development Index, and the best quality of life in the world. (Template:PDFlink)

Poverty figures show that 6.8% of Ireland's population suffer "consistent poverty" Template:PDFlink (2004).

Military

Ireland's armed forces are organised under the Irish Defence Forces (Óglaigh na hÉireann). The Irish Army is relatively small compared to other neighbouring armies in the region, but is well equipped, with 8,500 full-time military personnel (13,000 in the reserve army).[5]. This is principally due to Ireland's policy of pursuing a policy of neutrality, Template:Fact and its "triple-lock" rules governing participation in conflicts. Deployments of Irish soldiers cover UN peace-keeping duties, protection of the Republic's territorial waters (in the case of the Irish Naval Service) and Aid to Civil Power operations in the state. See Irish neutrality.

There is also an Irish Air Corps and Reserve Defence Forces (Irish Army Reserve and Naval Service Reserve) under the Defence Forces. The Irish Army Rangers is a special forces branch which operates under the aegis of the army.

Over 40,000 Irish servicemen have served in UN peacekeeping missions around the world.

Demographics

Genetic research suggests that the first settlers of Ireland, and parts of North-Western Europe, came through migrations from Iberia following the end of the most recent ice age [3] [4]. After the mesolithic, the neolithic and bronze age migrants introduced Celtic culture and languages to Ireland; these later migrants represent only a minority of the genetic heritage of Irish people ("Origins of the British", Stephen Oppenheimer, 2006) [5]. Culture spread throughout the island, and the Gaelic tradition became the dominant form in Ireland. Today, Irish people are mainly of Gaelic ancestry, and although some of the population is also of Norse, Anglo-Norman, English, Scottish, French and Welsh ancestry, these groups have been assimilated and do not form distinct minority groups. Gaelic culture and language forms an important part of national identity. The Irish Travellers are an ethnic minority group, politically (but not ethnically) linked with mainland European Roma and Gypsy groupsTemplate:Fact.

Languages

The official languages are Irish and English. Teaching of the Irish and English languages is compulsory in the primary and secondary level schools that receive money and recognition from the state. Some students may be exempt from the requirement to receive instruction in either language. English is by far the predominant language spoken throughout the country. People living in predominantly Irish-speaking communities, (the Gaeltacht), are limited to the low tens of thousands in isolated pockets largely on the western seaboard. Road signs are usually bilingual, except in the Gaeltacht, where they are in Irish only. The legal status of place names has recently been the subject of controversy, with an order made in 2005 under the Official Languages Act changing the official name of certain locations from English back to Irish (e.g. Dingle is now officially named An Daingean), sometimes despite local opposition, and, in Dingle's case, a plebiscite requesting a name change to a bilingual version. Most public notices are only in English, as are most of the print media. Most Government publications and forms are available in both English and Irish, and citizens have the right to deal with the state in Irish if they so wish. National media in Irish exist on TV (TG4), radio (e.g. Raidió na Gaeltachta), and in print (e.g. Lá and Foinse).

According to the 2006 census, 1,656,790 people (or 39%) in the Republic regard themselves as competent in Irish; however no figures are available for English-speakers, but it is thought to be almost 100%.

The Polish language is one of the most widely-spoken languages in Ireland after English and Irish: there are over 63,000 Poles resident in Ireland according to the 2006 census.

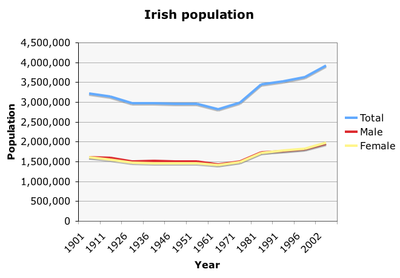

Recent population growth

Ireland's population has increased greatly in recent years. Much of this population growth can be attributed to the arrival of immigrants and the return of Irish people (often with their foreign-born children) who emigrated in large numbers in earlier years during periods of high unemployment. Approximately 10% of Ireland's population is now made up of foreign citizens.

The CSO has published preliminary findings based on the 2006 Census of Population. These indicate:

- The total population of Ireland on Census Day, April 23 2006, was 4,234,925, an increase of 317,722, or 8.1% since 2002

- Allowing for the incidence of births (245,000) and deaths (114,000), the derived net immigration of people to Ireland between 2002 and 2006 was 186,000.

- The total number of non-nationals (foreign citizens) resident in Ireland is 419,733, or around 10% (plus 1,318 people with 'no nationality' and 44,279 people whose nationality is not stated).

- The single largest group of immigrants comes from the United Kingdom (112,548) followed by Poland (63,267), Lithuania (24,628), Nigeria (16,300), Latvia (13,319), China (11,161), and Germany (10,289).

- 94.8% of the population was recorded as having a 'White' ethnic or cultural background. 1.1% of the population had a 'Black or Black Irish' background, 1.3% had an 'Asian or Asian Irish' background and 1.7% of the population's ethnic or cultural background was 'not stated'.

- The average annual rate of increase, 2%, is the highest on record – compared to 1.3% between 1996 and 2002 and 1.5% between 1971 and 1979.

- The 2006 population was last exceeded in the 1861 Census when the population then was 4.4 million The lowest population of Ireland was recorded in the 1961 Census – 2.6 million.

- All provinces of Ireland recorded population growth. The population of Leinster grew by 8.9%; Munster by 6.5%; and the long-term population decline of the Connacht-Ulster[6] Region has stopped.

- The ratio of males to females has declined in each of the four provinces between 1979 and 2006. Leinster is the only province where the number of females exceeds the number of males. Males predominate in rural counties such as Cavan, Leitrim, and Roscommon while there are more females in cities and urban areas.

A more detailed breakdown of these figures is available online. Census 2006 Principal Demographic Results

Detailed statistics into the population of Ireland since 1841 are available at Irish Population Analysis.

Religion

The Republic of Ireland is 88.4% nominally Roman Catholic, and has one of the highest rates of regular and weekly church attendance in the Western World[7]. However, there has been a major decline in this attendance among Irish Catholics in the course of the past 30 years. Between 1996 and 2001, regular Mass attendance, declined further from 60% to 48%[8] (it had been above 90% before 1973, and all but two of its sacerdotal seminaries have closed (St Patrick's College, Maynooth and St Malachy's College, Belfast). A number of theological colleges continue to educate both ordained and lay people.

The second largest Christian denomination, the Church of Ireland (Anglican), having been declining in number for most of the twentieth century, but has more recently experienced an increase in membership, according to the 2002 census, as have other small Christian denominations, and Islam. The largest other Protestant denominations are the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, followed by the Methodist Church in Ireland. The very small Jewish community in the state also recorded a marginal increase (see History of the Jews in Ireland) in the same period.

The patron saints of Ireland are Saint Patrick and Saint Bridget.

According to the 2006 census, the number of people who described themselves as having "no religion" was 186,318 (4.4%). An additional 1,515 people described themselves as agnostic and 929 as atheist instead of ticking the "no religion" box. This brings the total nonreligious within the state to 4.5% of the population. A further 70,322 (1.7%) did not state a religion.[9]

Religion and politics

The 1937 Constitution of Ireland gave the Roman Catholic Church a "special position" as the church of the majority, but also recognised other Christian denominations and Judaism. As with other predominantly Roman Catholic European states (e.g., Italy), the Irish state underwent a period of legal secularisation in the late twentieth century. In 1972, the articles mentioning specific religious groups, including the Catholic Church were deleted from the Irish constitution by the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland.

Article 44 remains in the Constitution. It begins:

- The State acknowledges that the homage of public worship is due to Almighty God. It shall hold His Name in reverence, and shall respect and honour religion.

The article also establishes freedom of religion (for belief, practice, and organisation without undue interference from the state), prohibits endowment of any particular religion, prohibits the state from religious discrimination, and requires the state to treat religious and non-religious schools in a non-prejudicial manner.

Catholic doctrine prohibits abortion in all circumstances, putting it in conflict with the pro-choice movement. In 1983, the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland recognised "the right to life of the unborn", subject to qualifications concerning the "equal right to life" of the mother. The case of Attorney General v. X prompted passage of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, guaranteeing the right to travel abroad to have an abortion performed, and the right of citizens to learn about "services" that are illegal in Ireland but legal outside the country (see Abortion in Ireland).

Catholic and Protestant attitudes in 1937 also disfavoured divorce, which was prohibited by the original Constitution. It was not until 1995 that the Fifteenth Amendment repealed this ban.

The Catholic Church was hit in the 1990s by a series of sexual abuse scandals and cover-up charges against its hierarchy. In 2005, a major inquiry was made into child sexual abuse allegations. The Ferns report, published on 25 October, 2005, revealed that more than 100 cases of child sexual abuse, between 1962 and 2002, by 21 priests, had taken place in the Diocese of Ferns alone. The report criticised the Garda and the health authorities, who failed to protect the children to the best of their abilities; and in the case of the Garda before 1988, no file was ever recorded on sexual abuse complaints (see Roman Catholic sex abuse cases).

Despite most schools in Ireland being run by religious organisations, a general trend of secularism is occurring within the Irish population, particularly in the younger generations. Many efforts have been made by secular groups, to eliminate the rigorous study of prayer in the first and sixth classes, to prepare for the sacraments of holy communion and confirmation. However religious studies as a subject was introduced into the state administered "Junior certificate" in 2001.

Culture

The island of Ireland has produced the Book of Kells, and writers such as George Berkeley, Jonathan Swift, James Joyce, George Bernard Shaw, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Oliver Goldsmith, Oscar Wilde, W.B. Yeats, Patrick Kavanagh, Samuel Beckett, John Millington Synge, Seán O'Casey, Séamus Heaney, Bram Stoker and others. Shaw, Yeats, Beckett and Heaney are Nobel Literature laureates. Other prominent writers include John Banville, Roddy Doyle, Séamus Ó Grianna, Dermot Bolger, Maeve Binchy, Frank McCourt, Edna O'Brien, Joseph O'Connor, John McGahern and Colm Tóibín.

Ireland is known for its Irish traditional music, but has produced many other internationally influential artists in other musical genres, such as the Alternative Rock group The Cranberries, Blues guitarist Rory Gallagher, folk singer Christy Moore, the Wolfe Tones and singer Sinéad O'Connor.

In classical music, the Island of Ireland was also the birthplace of the notable composers Turlough O'Carolan, John Field (inventor of the Nocturne), Gerald Barry, Michael William Balfe, Sir Charles Villiers Stanford and Charles Wood.

Successful entertainment exports in the late twentieth century include acts such as Horslips, U2, Thin Lizzy, Boomtown Rats, The Pogues, Ash, The Corrs, Clannad, Boyzone, Ronan Keating, The Cranberries, Gilbert O'Sullivan, Westlife and Enya, and the internationally acclaimed dance shows Riverdance and Lord of the Dance. In the early twenty-first century, Damien Rice and The Thrills rose to international fame. The Frames are a popular band in Ireland who are on the rise world-wide, although their status as possibly the most well-liked live band in Ireland is under threat from newer bands like Bell X1. The Blizzards are a ska-pop band from Mullingar, who gained a sudden surge of popularity following their 2006 album release.

Notable Hollywood actors from the Republic of Ireland include Maureen O'Hara, Barry Fitzgerald, Maureen O'Sullivan, Richard Harris, Peter O'Toole, Pierce Brosnan, Gabriel Byrne, Brendan Gleeson, Daniel Day Lewis (by citizenship), Colm Meaney, Colin Farrell, Jonathan Rhys-Meyers and Cillian Murphy.

Ireland has produced a number of talented sportsmen and women. In soccer, former players include Roy Keane, Johnny Giles, Liam Brady, Denis Irwin, Packie Bonner, Niall Quinn and Paul McGrath, while footballers whose careers are ongoing include Shay Given,Damien Duff,and Robbie Keane. In rugby Ireland has produced Ronan O'Gara, Brian O'Driscoll, Paul O'Connell, David Wallace and Keith Wood while in athletics Sonia O'Sullivan and Derval O'Rourke have had success in international events. Notable Gaelic Athletic Association players include the now retired pair of DJ Carey and Peter Canavan. Ken Doherty is a former World Champion Irish snooker player. A famous bareknuckled boxer although he was not born in Ireland, John L. Sullivan, born 1858 from Irish immigrants was and is historically the first modern world heavyweight champion. Barry McGuigan was also a world champion boxer, while Bernard Dunne is a current European champion and is expecting a crack at a world title later in 2007.

Robert Boyle was a seventeenth-century physicist and discovered Boyle's Law. Ernest Walton of Trinity College Dublin shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Physics for "splitting the atom". William Rowan Hamilton was a significant mathematician.

Ireland is at the forefront of recognising equal rights for its gay citizens, see Gay rights in the Republic of Ireland.

Transport

The Republic of Ireland has three main international airports (Dublin, Shannon, and Cork) that serve a wide variety of European and intercontinental routes with scheduled and chartered flights. The national airline is Aer Lingus, although low cost airline Ryanair is the largest airline. The route between Dublin and London is the busiest international air route in the world.Template:Fact

Railways services are provided by Iarnród Éireann. Dublin is the centre of the network, with two main stations (Heuston and Connolly) linking to the main towns and cities. The Enterprise service, run jointly with Northern Ireland Railways connects Dublin with Belfast.

The motorways and major trunk roads are managed by the National Roads Authority. The rest of the road network is managed by the local authorities in each of their areas.

Regular ferry services operate between the Republic of Ireland and Great Britain, the Isle of Man and France.

International rankings

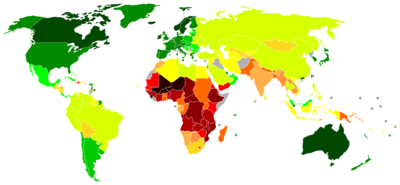

| World map indicating Human Development Index (2004). Ireland ranked 4th highest in the world at 0.956. |

Political and economic rankings

- Political freedom ratings - political rights and civil liberties both rated 1 (the highest score available)

- Press freedom - 1st equal freest in the world at 0.50

- GDP per capita at purchasing power parity - 4th highest in the world at I$40,610

- Human Development Index - 4th highest in world at 0.956

- Literacy Rate - Equal first with a ranking of 99.9%

- Unemployment rate - 28th lowest in the world at 4.30%

- Corruption - 18th equal least corrupt in world at 7.4 on index

- Economic Freedom - 3rd freest at 1.58 on index

Health rankings

- Fertility rate- 133rd most fertile in the world at 1.86 per woman

- Birth rate - Joint 136th most births in the world at 14.45 per 1000 people

- Infant mortality - 196th most deaths in the world at 5.39 per 1000 live births

- Birth rate - Joint 136th most births in the world at 14.45 per 1000 people

- Death rate - Joint 110th highest death rate in the world at 7.85 per 1000 people

- Life Expectancy - 32nd highest in the world at 77.56 years

- Suicide Rate - 33rd highest suicide rate in the world at 21.4 for males and 4.1 for females

- HIV/AIDS rate 122nd most cases in the world at 0.10%

Other rankings

- CO2 emissions - 30th highest emissions in world at 10.3 tonnes per capita

- Electricity Consumption - Joint 61st highest consumption of electricity in world at 22,790,000,000 kWh

- Broadband uptake - 23rd highest/8th lowest uptake in OECD at 6.7%

- Beer consumption - 2nd highest at 131.1 litres per capita

See also

- List of Ireland-related topics

- Republic of Ireland football team

- List of flags of the Republic of Ireland

References

- ↑ Article 2, The Republic of Ireland Act, 1948, Government of Ireland

- ↑ Template:PDFlink

- ↑ EU to call country 'Éire Ireland', Irish Examiner, 27 June 2006.

- ↑ http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0107648.html

- ↑ Irish Defence Forces, Army (accessed 15 June 2006)

- ↑ Donegal, Cavan, Monaghan only. Remaining Ulster counties are in Northern Ireland

- ↑ Weekly Mass Attendance of Catholics in Nations with Large Catholic Populations, 1980-2000 World Values Survey (WVS)[1]

- ↑ Catholic World News June 1, 2006: Irish Mass attendance below 50% [2]

- ↑ Final Principal Demographic Results 2006

Bibliography and further reading

- Bunreacht na hÉireann (the 1937 constitution) (Template:PDFlink)

- The Irish Free State Constitution Act, 1922

- J. Anthony Foley and Stephen Lalor (ed), Gill & Macmillan Annotated Constitution of Ireland (Gill & Macmillan, 1995) (ISBN 0-7171-2276-X)

- FSL Lyons, Ireland Since the Famine

- Alan J. Ward, The Irish Constitutional Tradition: Responsible Government and Modern Ireland 1782–1992 (Irish Academic Press, 1994) (ISBN 0-7165-2528-3)

- Some of the material in these articles comes from the CIA World Factbook 2000 and the 2003 U.S. Department of State website.

- OECD Information Technology Outlook 2004

External links

- Áras an Uachtaráin — Official presidential site

- Irish genes from Spain

- Information on the Irish State — Governmental portal

- Ireland Story — History, geography and current affairs

- Chief Herald of Ireland — Flags, Seals, Titles

- From the Iron age Celts or just a seafaring passerby

- Myths of British ancestry

- Taoiseach — Official prime ministerial site

- Tithe an Oireachtais — Houses of Parliament, official parliamentary site

Template:Template group Template:Template group Template:Template group

af:Republiek van Ierland am:አየርላንድ ሪፑብሊክ ar:جمهورية إيرلندا an:Irlanda roa-rup:Irlanda ast:República d'Irlanda az:İrlandiya zh-min-nan:Éire be:Рэспубліка Ірляндыя bs:Republika Irska br:Republik Iwerzhon bg:Република Ирландия ca:República d'Irlanda cv:Ирланди cs:Irsko co:Irlanda cy:Gweriniaeth Iwerddon da:Irland (land) de:Irland arc:ܩܘܛܢܝܘܬܐ ܕܐܝܪܠܢܕ et:Iirimaa el:Δημοκρατία της Ιρλανδίας es:Irlanda eo:Irlando (lando) eu:Irlandako Errepublika fa:ایرلند fo:Írland fr:Irlande (pays) fy:Ierlân ga:Poblacht na hÉireann gv:Pobblaght Nerin gd:Poblachd na h-Éireann gl:Irlanda - Éire ko:아일랜드 hsb:Irska hr:Irska io:Irlando id:Republik Irlandia ia:Republica de Irlanda os:Ирланди is:Írska lýðveldið it:Irlanda he:אירלנד kk:Ирландия kw:Repoblek Iwerdhon ku:Komara Îrlanda la:Irlandia lv:Īrija lb:Irland (Land) lt:Airija lij:Éire li:Ierland hu:Írország ms:Ireland na:Republik Ireland nl:Ierland (land) nds-nl:Ierlaand (laand) ne:आयरल्याण्ड ja:アイルランド no:Republikken Irland nn:Republikken Irland nrm:Républyique d'Irlande nov:Republike de Irlande oc:Irlanda (estat) pam:Republic of Ireland nds:Irland pl:Irlandia pt:República da Irlanda ro:Republica Irlanda rmy:Republika Irland rm:Republica da l'Irlanda ru:Ирландия war:Republika han Irlandia se:Irlánda sco:Republic o Ireland sq:Irlanda simple:Republic of Ireland sk:Írsko sl:Irska (država) sr:Република Ирска sh:Irska fi:Irlanti sv:Irland tl:Republika ng Irlanda th:สาธารณรัฐไอร์แลนด์ vi:Cộng hòa Ireland tg:Ҷумҳрии Ирландия tpi:Aialan tr:İrlanda udm:Ирландия uk:Республіка Ірландія ur:جمہوریہ آئرلینڈ vo:Lireyän fiu-vro:Iirimaa zh-yue:愛爾蘭共和國 diq:İrlanda bat-smg:Airėjė zh:爱尔兰共和国