Battle of the Ia Drang

A month-long action fought in the Vietnam War in 1965, the Battle of the Ia Drang was a campaign, composed of multiple battles against the a division-sized force from the People's Army of Viet Nam (PAVN). Most western histories focus on the second battle.[1] It is an especially informative topic, since, in addition to the U.S. reports that long have been available, some of the key commanders on both the North Vietnamese and U.S. sides have met as friends, and discussed the different perspectives.[2] South Vietnamese reporting is also available.[1]

The engagement took place in the South Vietnamese II Corps tactical zone area, headed by BG Vinh Loc.

On the North Vietnamese side, the senior commander for the region was the late Chu Huy Man, then a brigadier general and subsequently one of the few men ever to hold the rank of Senior General.[2] He faced II Vietnamese Corps under BG Vinh Loc,[3] supported by US I Field Force under MG Stanley Larsen. Under I Field Force was the first operational U.S. airmobile unit, the 1st Cavalry Division, commanded by MG Harry Kinnard. [4].

The first and better-known battle in the West, in the Plei Me area, was the first combat action involving a United States Army an airmobile unit of divisional strength. This took place on November 14 to November 24, 1965, with the main action by the 2nd Brigade on the 14th-. It was made well known by the book We Were Soldiers Once... And Young, subsequently a movie, written by LTG (ret.) Hal Moore, a battalion commander in the U.S. action and Joe Galloway, a reporter who was at Moore's side during the LZ X-Ray engagement[5] where Moore's unit, the 1/7 Cavalry fought the 7/66 PAVN battalion under Nguyen Huu An. They said that this had been called the "Pleiku Campaign" within the Army,[6] but this terminology was not widely used. Subsequently, Moore and Galloway returned to Vietnam in the 1990s, Galloway more recently in 2005, and reviewed the battle with their one-time enemies.

The second battle was fought by troops from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) Airborne Brigade, under BG Du Quoc Dong, with LTC Ngo Quang Truong, chief of staff under Dong, in tactical command. Another U.S. officer, who would rise to the highest ranks, was an adviser to the Airborne at the battle: then-major H Norman Schwarzkopf Jr.. Schwarzkopf held Truong in the highest respect. [7]

Background

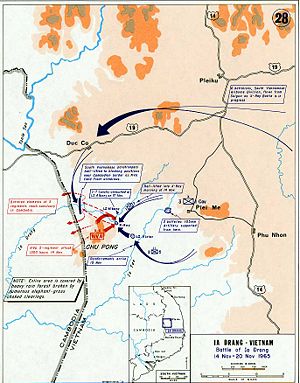

The battlefield covered 1,500 square miles of generally flat to rolling terrain drained by an extensive network of rivers and small streams flowing to the west and southwest across the border into Cambodia. The dominating feature of the terrain was the Chu Pong Massif in the southwestern corner of the area, straddling the Cambodian-Vietnamese frontier. [8]

It was a major area of North Vietnamese infiltration. Within it, Route 14 interconnects Ban Me Thuot, Pleiku, Kontum and Thua Thien, and had been built specifically for ARVN movement against North Vietnamese infiltration.[9] Route 19 connected An Khe to Pleiku.

North Vietnamese plan

There has been much controversy if the North Vietnamese specifically intended to engage the 1st Cavalry, or if that confrontation developed during the execution of a general PAVN plan to operate in central Vietnam. It is usually agreed that if the PAVN had been successful, they could have cut South Vietnam in half. A broader context was provided by General Man, who said that a prior plan, before the arrival of the airmobile force, as well as the U.S. Marine Corps units at Danang, was to attack Plei Me and ambush the expected ARVN relief force that would approach Plei Me on Route 14. After defeating that force, he then expected to capture Pleiku, and then move down the South Vietnamese coast on Route 19, potentially cutting South Vietnam in half. Man observed that while that specific plan was not executed, it was very similar to the final assault on South Vietnam in 1975. [10]

According to MG Huong Phong, chief of the Vietnamese army Military History Insitute, said that he had been sent south, after the arrival of the U.S. airmobile unit, to study its tactics. Phuong said that the PAVN plan was to attack the United States Army Special Forces camp at Plei Me, and to ambush the expected ARVN relief column. That ambush, Phuong told Moore and Galloway, was expected to draw the airmobile forces to relieve the ARVN, at which time the PAVN could gain experience with the new U.S. capabilities.

Airmobile units are light infantry with regularly assigned helicopters, which make most tactical movements by helicopter. Earlier in 1965, there had been promising combat demonstrations by the 173rd Airborne Brigade, but the helicopters were ad hoc attachments and the team was not well practiced. From the U.S. perspective, Ia Drang demonstrated the fundamentally new capabilities, as well as the liabilities, of large, well-integrated airmobile forces. [4] Phoung, in the first meeting with Moore and Galloway, said "You jumped all over, like a frog, even into the rear area of our troops...you created disorder among our troops." Phuong wrote a pamphet, How to fight the Americans. [11]

Man, referring to a change of plan after U.S. forces came into II Corps, said "We used the [revised] plan to lure the tiger out of the mountain...I had confidence the Americans will use their helicopters to land in our rear, land in the Ia Drang area." His command post was south of the Chu Pong Massif.[12] Hay assumed "The implications of an ambush deep with what was thought to be secure territory must have stunned the North Vietnamese Army's high command."[13]

Plei Me battles

The first PAVN attacks came against Plei Me, but II Corps became aware of other units maneuvering to "fork" them between Pleiku and Plei Me. [14]

Attack of CIDG Camp

On Octber 19, PAVN troops attacked the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) camp, 40 km south of Plei Me city. The camp had a U.S. Army Special Forces "A" team, a ARVN Luc Luong Dac Biet (LLDB) special forces team,[15] and around 400 Montagnard irregulars, with their families.

A PAVN battalion of the NVA 33rd regiment shelled the camp, but did not press to overrun it. They did, however, surround the area with antiaircraft artillery , as a successful "flak trap" for aircraft. They also placed artillery and mortars on high ground, with a clear goal of ambushing the expected relief column.[16]

ARVN dilemma

By 22 October, two North Vietnamese regiments were confirmed to be in the Plei Me area, suggesting the North Vietnamese were making a serious push to control the Central Highlands. Plei Me proper was being attacked by the 33rd Regiment, but the 32nd Regiment had set ambushes along the road to Pleiku, from which a South Vietnamese relief column would come.

The commander of the Vietnamese II Corps tacical zone, BG Vinh Loc, could lose Plei Me if he did not relieve it, but if the troops in Pleiku went to Plei Me, Pleiku might come under attack by additional North Vietnamese troops. It was known that the 66th Regiment was somewhere in the Central Highlands. [17]

Rescue column launched and ambushed

Beginning on the 21st, the relief moved by road toward Plei Me, and indeed was attacked by the 32nd Regiment along with elements of the 33rd, whose location had not been confirmed. The ARVN force was organized into three groups, the Rangers going down Route 6C, the 1/42 Infantry by another land route, and a fourth heliborne reserve.[16] That helicopter reserve had then-Major "Charging Charlie" Beckwith's Special Forces "B" detachment, designated team B-52 or Project DELTA, and also reporter Joe Galloway. Beckwith told Galloway that he wasn't just a reporter, but a machine gunner.

He allowed as how I had "done good" as a machine gunners and he thanked me for the help. Then he said: You have no weapon. I said that, despite the use he had made of me these last days, I was still technically speaking a non-combatant. He had a sergeant bring an M-16 rifle and a sack full of loaded magazines. Beckwith said: "Ain't no such thing in these mountains, boy. Take the rifle."[18]

After the overall battle, Galloway was the only reporter in the Vietnam War to receive the Bronze Star for valor in combat. [19] and two companies from the ARVN 22nd Ranger Battalion.[16]

- 3rd Armored Regiment (-) comprising 12 M41 tanks and 8 M113 armored personnel carriers; 1st and 2nd Ranger companies, some troops on foot, some scouting and others riding with the armor for combined operations.

- 21st Ranger Battalion headquarters, 4th Company, an engineer squad, and two 105mm howitzers, with APCs and armored scout cars.

Ambush

At a position where trees prevented the armored vehicles from dispersing, the NVA prepared a L-shaped ambush. The main force, of 4 battalions from the 32nd and 33rd NVA Regiments, were in fortifications. To the rear, a force approximately 400 soldiers attack the rear of the column, while troops on higher ground would use anti-tank rockets, heavy machine guns, and light artillery against the troops and armored vehicles.

Since the column was limited to the speed of the foot-mounted scouts, properly searching for ambushes, they moved slowly, and the NVA sprung the ambush at 3 PM. While the force was able to neutralize much of the force on high ground, they lost many of their vehicles, and formed night defensive positions. While the 22nd Ranger Battalion, the reserve force, was lifted into the area by 1st Cav helicopters, they arrived around dusk and could not link up until the next day. South Vietnamese C-47 aircraft dropped illuminating flares all night, and U.S. artillery harassed the NVA. In the dark and confusion, some NVA soldiers inadvertently walked into the Ranger positions, thinking they were their own, and were captured after reporting in.

Defense of Plei Mei

When Beckwith arrived at the camp, on the 22nd, he took command. [19] The full relief column arrived at Plei Me on 25 October; there were problems in the way they used their armored vehicles, essentially treating them as fixed fortifications. [20] They drove off the enemy on the 27th, although there is no evidence the PAVN expected to hold the ground, as opposed to inflict casualties on the rescue column.

The U.S. battle

At the operational level, it was essentially a pursuit of three foot-mobile regiments, under divisional command, by single brigades and supporting forces rotating out of a U.S. division headquarters. As opposed to the slightly later Battle of Bong Son, the full airmobile division was not in combat at one time. [21]

Stretched to the limit, the South Vietnamese asked the U.S. forces for assistance. The U.S. I Field Force Vietnam (corps equivalent) commander for the area, MG Stanley Larsen, told GEN William Westmoreland that he thought the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) was ready, and got permission for it to use its mobility to bypass the road ambushes. Since the PAVN along the road had planned to ambush trucks, there was not an issue of not being able to find the relieving troops. While the heliborne U.S. troopers could be heard miles away, their actual attack zones could not be determined until they swooped to a landing. A brigade of the "1st Cav" was dispatched to take on the three PAVN regiments.

Early movements by 1st Cavalry Division (airmobile)

Task Force (TF) INGRAM, a reinforced battalion of 2/12 Cavalry, moved by helicopter from An Khe to Plei Me, bypassing the 23nd regiment. U.S. aircraft supplied Plei Me with parachute-dropped supplies.

Division commander Harry Kinnard thought he might be able to outmaneuver and confront a large force, and moved his 1st Brigade to Pleiku, where it took operational control of TF INGRAM, provided fire support to the ARVN force now freed to move to Plei Me, and providing a reserve.

By this time, 1st Cav units had flown from Pleiku to areas within striking range of the Plei Me area. Their field bases were not in Plei Me, but in a position to give fire support and move heliborne troops anywhere in the area, potentially cutting of PAVN retreat.

Late that night, the 33rd PAVN Regiment began to withdraw to the west, leaving a strong rear guard. The next phases were to be a matter of maneuver, with the PAVN moving under cover and the Cav engaging them when they were found. In airmobile doctrine, the Cav did not need to hold ground, but could attack and fly away.

Battle reaches the divisional level

1st Cav's responsibility changed, by order of Westmoreland, to "search and destroy" against all enemy forces in the region. One of the reasons for the change of scope was intelligence that "a field front (divisional headquarters) was controlling the enemy regiments. If so, this operation marked the first time any U.S. unit in Vietnam had opposed a division-size unit of the North Vietnamese Army under a single commander, " [4] Chu Huy Man. [22] It operated by brigade; while the 1st Cav was a division, it had only enough helicopters to lift one full brigade at a time, plus air cavalry scout

In the pursuit, the first contact was made by Cav platoons that encountered a force in battalion strength, six miles southwest of Plei Mei. The contact was soon too close for U.S. fire support. After "finding and fixing" the enemy, the U.S. units airlifted out, but set ambushes for 3 November.

The ambush overwhelmed the enemy heavy weapons unit, and the ambush patrol pulled back to its field base and strengthened its defenses. By late that evening, it was under attack by several North Vietnamese companies, and was in dange of being overrun by midnight. Reinforcements arrived in forty minutes. It was the first time:

- a unit, under heavy fire, was reinforced, at night, by helicopter lift into an unfamiliar landing zone

- aerial rocket artillery (2.75" unguided rockets fired from armed helicopters was used at night, and as close as 50 meters to friendly forces.

LZ X-Ray

On November 14, after preliminary surveys with the brigade commander, [23] then-LTC Hal Moore took 450 men of the 1/7 Cavalry battalion -- the same unit that George Armstrong Custer took to a place called the Greasy Grass, or the Little Big Horn -- to a place with no name other than the map designation, Landing Zone X-Ray (LZ X-Ray), and was soon in a desperate fight with the 7/66 PAVN battalion under then-Nguyen Huu An. Both An and Moore became lieutenant generals.

The North Vietnamese wanted to test tactics against the new airmobile units, one of which was "hugging the belt" -- staying in such close contact that the U.S. support weapons could not be used for fear of fratricide. In his after-action report, Moore said,

Fire support to be truly effective must be close-in. Against heavy attacks such as the ones we defended against, some enemy will get very close or even intermingled with friendly in the high grass. Bringing fires in promptly, “walking them in” extremely close helped us greatly. The commander cannot wait until he knows exactly where all his men are. If he does, in a heavy action, he will get more men killed by waiting than if he starts shooting immediately. Once the enemy gets as close as 25 meters out or intermingled then he has the friendly fighting on his terms, with those who have made it that close. Close fire support then can be used to cut off his follow-up units, and they will be there.[23]

Close air support was brought in much more closely than in other operations by the forward air controller, 1LT Charles Hastings. When John Stoner, the Air Force commander, asked Moore, “How is my forward air controller doing?” He answered, “John, he is doing a magnificent job, but remember he is my forward air controller.”[24] Air resupply and medical evacuation, by both Army and Air Force aviators, also were critical; three Medals of Honor were much later presented, as a result of of Congressional action to waive the statutory time limit for issuance after the action. An Air Force pararescueman, A1C William "Pits" Pitsenbarger, who was assigned to an evacuation helicopter, without orders, joined the ground force to increase their medical support. He died there; his Air Force Cross was subsequently upgraded to the Medal of Honor.[25] Bruce Crandall, then a major commanding the Army helicopter company in direct support, spent 14 hours in the air, repeatedly flying in and out of X-ray, and, in 2007, received the Medal of Honor[26]. His wingman, Ed W. Freeman, also received the Medal.

Rick Rescorla was one of Moore's platoon leaders. On 9-11 Attack, he was Vice President of Security for the largest tenant in the World Trade Center, and died while ensuring that his people were evacuated.

Approximately 4,000 NVA hit LZ X-Ray, and the situation, for a time, was desperate for the Cavalry. Eventually, they gained control, but the original unit had close to 50 percent casualties, with 79 dead. It is estimated that the NVA took between 400 and 2500 dead, but the U.S. force made an orderly retreat; Moore considered the battle a draw.

After 1/7 Cavalry withdrew, two other battalions, moved into the general area. 2/5 Cavalry under LTC Robert Tully, marched in from LZ Victor. 2/7 Cavalry, commanded by LTC Robert McDade airlanded at LZ Columbus. The two battalions began moving toward the X-ray area. [27]

Air attacks

After breaking off ground combat, it was believed the enemy had withdrawn into Chu Pong Massif. Kinnard asked for ARC LIGHT B-52 strikes. B-52s were requested, to neutralize the Chu Pong high ground, and they attacked it, close to the left flank of ground units, for 6 days. It was the first operation in the war in which B-52 strikes were integrated into the overall tactical plan. From the U.S. perspective, their effectiveness could only be inferred. After the attacks began, there were no further attacks from Chu Pong. [24] PAVN Gen. Man said his command post was south of Chu Pong and B-52 strikes hit within 1000 yards of his position, temporarily deafening him. He told Moore and Galloway, however, that his troops were dispersed and entrenched, and took relatively few casualties. [28]

LZ Albany

On the 17th, 2/7 Cavalry moved to LZ Albany. McDade did not have artillery fire into his direction of march, as did the other relieving units. [29]They ran into an ambush by LTC An's fresh reserve battalion, 8/66 PAVN,[30] as well as elements of 1/33 and the headquarters of 3/33. [27] 151 Americans died, with casualties much higher than at X-Ray. Not all bodies were recovered until Moore, then a colonel, led a brigade back into the area during the Battle of Bong Son. NVA casualties were even higher.

Westmoreland did not know about it until he visited a hospital on the 18th and encountered the wounded.[31] BG Richard Knowles, assistant division commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, called a news conference and denied there had been an ambush at Albany; he called it a "meeting engagement" with light to moderate casualties. NBC cameraman Vo Huynh, who had been present at the relief, denied that it was a prepared ambush, saying that the NVA had not prepared their automatic weapons, had rice bowls scattered around the area, and were wearing their packs. Huynh, who may have been a Viet Minh officer against the French, did not deny it was an ambush, but a hasty one, with perhaps 20 minutes of PAVN prepration. Whether a meeting engagement or a well-prepared ambush, it had the highest casualties of any American engagement since the Korean War.[32]

Galloway, who had flown back to Albany and was at Knowles' briefing, shouted an obscene denial of the casualties to Knowles. Westmoreland called Larsen, who also had been unaware of the ambush. Larsen asked Kinnard, Knowles, and COL Tim Brown, 3rd Brigade commander, why Westmoreland had not been told. In a telephone interview years later, Larsen told Galloway that none of the three claimed to know about it. Larsen later gave Galloway an affidavit saying "They were lying and I left and flew back to my headquarters and called Westy [Westmoreland] and told him so, and told him I was prepared to bring court-martial charges against each of them. There was a long silence on the phone and then Westy told me: No, Swede [Larsen], let it slide."[33] The controversy was not, as some reports have argued, about whether the North Vietnamese had carefully prepared the ambush, but about the denial of casualties. It was only in the postwar meetings that General An learned he was not still fighting Moore's unit, suggesting that, indeed, it was not an extensively prepared ambush. [34] Questions were raised if McDade was at fault, and, after Kinnard had had the deputy brigade commander investigate and found the troops were not blaming McDade, and Kinnard was known for loyalty down. [35]

U.S. Lessons learned and handoff to ARVN

In his after-action report from LZ X-Ray, Moore expounded on how airmobile infantry should move once on the ground: "cautiously aggressive. The enemy must be pinned down by fire. Small unit, squad sized fire and movement must be conducted to perfection. This is extremely important. If not conducted correctly, men will get hit and the problem is then compounded when other men stop firing to try to recover casualties. Then they also get hit in many cases and soon, combat effectiveness of the squad, platoon, etc. is in danger of being lost." He recommended "reconnaissance by fire", shooting first when contact was suspected, which could take the initiative from the enemy.

PAVN General Man, however, believed the North Vietnamese had won. "Here we showed you very high spirit; very high determination. This is the first time we try our tactics: Grab them by the belt buckle~ The closer we come to you the less your firepower is effective. After the Ia Drang battles, we are sure we will win the limited war. We will destroy American strength and force them to withdraw.[36]

The US military viewed the battle as proof that its helicopter-assault tactics and strategy of attrition could win the war. The NVA saw in the heavy US casualties inflicted at LZ X-Ray and LZ Albany vindication for its belief that communist troops could also inflict sufficient pain on US forces. Clearly, each side saw only the results it wanted to see, and each thought it had hurt the other more than it had.[37]

As the LZ Albany relief concluded, the 2nd Brigade commander, COL William "Ray" Lynch, moved artillery to LZ GOLF, to support the ARVN movement. Lynch moved his command post to the Duc Co special forces camp, from which the ARVN Airborne battalions were to move out on the 19th. [38]

The ARVN battle

In Operation Thần Phong 7, ARVN Airborne units, with U.S. artillery support, On 20 November, South Vietnamese airborne forces, supported by US artillery, encountered the 320th Regiment's 635th and 334th Battalions along the Cambodian border. [39] The 635th retreated, leaving the 334th to take heavy casualties; its regimental headquarters could not contact it for several days.[40]

According to Schwarzkopf, part of the reason the ARVN was conducting this part of the battle was the danger that U.S. troops might cross the Cambodian border. He quotes Truong as saying, "On your map, the Cambodian border is located here, ten kilometers east of where it appears on mine. In order to execute my plan, we must use my map rather than yours, because otherwise we cannot go around deeply enough to set up our first blocking force. So, Thieu ta Schwarzkopf"-thieu ta (pronounced "tia-tah") is Vietnamese for "major"-"what do you advise?"The map in Schwarzkopf's book does show the 3rd battalion moving through Cambodia.

Schwarzkopf responded, "The prospect of letting an enemy escape into a sanctuary until he was strong enough to attack again galled me as much as it would any soldier. Some of these fellows were the same ones I'd run into four months earlier at Duc Co; I didn't want to fight them again four months from now. So why should I assume that my map was more accurate than Truong's? "I advise that we use the boundary on your map." The map in Schwarzkopf's book does show the 3rd battalion moving through Cambodia. He wrote that Truong seemed to be able to call in accurate artillery fire on PAVN he could not see. [41]

Nguyen Van Tin rejects Schwarzkopf's assumption that LTC Truong, the tactical commander, had an uncanny ability to predict the enemy, but that Truong actually followed guidance from ARVN II Corps. [42] He wrote Communist forces that Truong took under fire were actually under surveillance by Special Forces Rangers (Army of the Republic of Viet Nam).

Regardless of how Truong found the enemy, after the combat with American and South Vietnamese forces, retreated into their Cambodian sanctuary for six months of recuperation. Washington denied requests to pursue them. [43]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Nguyen Van Tin, The Ia Drang Valley Battle? Which One?, Nguyen Van Hieu website

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Moore, Harold G. (Hal) & Joseph L. Galloway (2008), We are soldiers still: a journey back to the battlefields of Vietnam, Harper Collins

- ↑ Nguyen Van Tin, General Hieu's Resume, Nguyen Van Hieu website

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Hay, John H. Jr., Chapter II: Ia Drang (October-November 1965), Vietnam Studies: Tactical and Materiel Innovations, Center for Military History, U.S. Department of the Army, p. 11

- ↑ Moore, Harold G. (Hal) & Joseph L. Galloway (1999), We Were Soldiers Once...and Young: Ia Drang - the Battle That Changed the War in Vietnam, Random House

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, p. 13

- ↑ Schwarzkopf, H Norman, Jr. (1992), It Doesn't Take a Hero, Bantam, pp. 122-123

- ↑ Hay, p. 10

- ↑ Nguyen Van Tin, The Unfolding of Strategic and Tactical Moves of Pleime Campaign, Nguyen Van Hieu website

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, pp. 35-36

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, pp. 28-30

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, pp. 35-36

- ↑ Hay, p. 13-14

- ↑ Hay, p. 10-11

- ↑ Rottman, Gordon L. & Ron Volstad (1990), Vietnam Airborne: 1940-90, Osprey Publishing, pp. 30-31

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Tran Quoc Canh (6/2005), "Plei Me Battle", Ða Hiệu magazine

- ↑ Hay, p. 11

- ↑ Galloway, Joseph L., A Combat Reporter Remembers the Siege at Plei Me

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Stanton, Shelby L. (2003), The Rise and Fall of an American Army

- ↑ Starry, Donn A. (1982), Armored Combat in Vietnam, Ayer Publishing, ISBN 0881430056

- ↑ Galvin, John R. (1969), Air Assault: the development of airmobile warfare, Hawthorn Books

- ↑ Cash, John A., 1: Fight at Ia Drang, Seven Firefights in Vietnam, Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Moore, Harold G. (Hal) (9 December 1965), After Action Report, IA DRANG Valley Operation 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Stoner, John R. (September-October 1967), "The Closer the Better", Air University Review

- ↑ Gomez-Granger, Julissa (May 29, 2007), Medal of Honor Recipients: 1979-2007, Congressional Research Service, pp. 29-30

- ↑ Miles, Donna (February 27, 2007), "Newest Medal of Honor Recipient Inducted Into Pentagon Hall of Heroes", American Forces Press Service

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Swager, Brent (October 1999), "Rescue at LZ Albany", Vietnam Magazine

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, p. 36

- ↑ Leonard, Steven M. (July-August 1998), "Steel Curtain: The Guns on the Ia Drang", Field Artillery, p. 20

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, p. 11

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, p. 123

- ↑ Coleman, J. D. (1998), Choppers: The Heroic Birth of Helicopter Warfare, Macmillan, ISBN 0312966350, pp. 270-271

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, pp. 123-124

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, p. 122

- ↑ Coleman, p. 271

- ↑ Moore & Galloway 2008, pp. 35-36

- ↑ Pribbenow, Merle L. (January-February 2001), The Fog of War: The Vietnamese View of the Ia Drang Battle, "Nguyen Van Hieu website", Military Review

- ↑ Coleman, p. 277

- ↑ Vinh Loc, Chapter VI: Phase 3, The "Thần Phong 7" Operations From 18 to 26 November 1965, The Coup de Grace at Ia Drang, Why Pleime?

- ↑ Pribbenow, citing Gen. Phuong's:"Several Lessons on Campaign Planning and Command Implementation During the Plei Me Campaign," The Plei Me Victory: Looking Back after 30 Years. Military History Institute and 3rd Corps (Hanoi: People's Army Publishing House, 1995), pp. 55-56

- ↑ Schwarzkopf, pp. 123-125

- ↑ Nguyen Van Tin, General Schwarzkopf's Naïveté In the Ia Drang Battle, Nguyen Van Hieu website

- ↑ Bruscino, Jr, Thomas A. (2006), Out of Bounds. Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare, Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, ADA454497, Combat Studies Institute Occasional paper no. 17, p. 18