Medicine

Medicine is the oldest branch of health science. Medicine refers both to an area of knowledge, (human health, diseases and treatment), and to the applied practice of that knowledge. Medicine promotes health through the study of human biology, and the diagnosis and treatment of disease and injury. The practice of Medicine is considered to be both an art and an applied science. The art is in the doctor-patient relationship that underlies the gathering of data, its interpretation, and the provision of therapy in clinical medicine. The practitioners of medicine, called physicians, hold doctorate degrees and have undergone a period of clinical apprenticeship called internship and residency training. Nearly all countries and legal jurisdictions have legal limitations on who may practice medicine.

Medical doctors have established a standard protocol in the evaluation of patients that is uniform around the world and throughout the varying medical and surgical specialties: the patient history, physical examination and the analysis of laboratory results.

The way that a patient's treatment is considered is also formulated in a manner that is generally accepted among all of the world's physicians. This involves establishing a diagnosis and prognosis for each presenting complaint, and has been used, by and large, since Aristotle's time in the Fourth Century BC. [1].The treatment plan advocated for any individual case largely depends on the specific diagnosis, and is also influenced by the prognosis. (need specific examples)

Overview of Specialties in Medicine

Medicine comprises hundreds of specialized branches. A basic distinction in medical specialties is between surgical and non-surgical areas, mainly because postgraduate training after medical school generally begins with either a medical or surgical internship, and one or the other is a pre-requisite for further training. Examples of the specialties and fields of medicine include cardiology, pulmonology, neurology, and public health. Most of these specialities are further divided into sub-specialties. For example, the specialty of orthopedic surgery includes: sports medicine, pediatric orthopedic surgery, hand surgery, xxxx .

The word 'Medicine' is also often used by medical professionals as shorthand for internal medicine, the non-surgical aspects of adult care. Physicians certified in Internal Medicine in the USA have completed a X year residency after graduating from medical school. Some train for an additional "Chief Resident" year before clinical practice. Other physicians trained in internal medicine subspecialize by training in a fellowship, such as gastroenterology, cardiology, pulmonology,

History of medicine

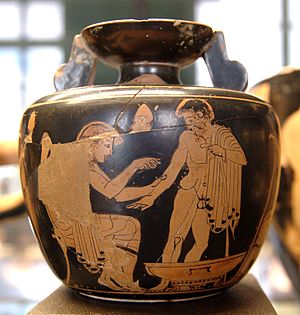

The earliest type of medicine in most cultures was the use of plants (Herbalism) and animal parts. This was usually in concert with 'magic' of various kinds in which: animism (the notion of inanimate objects having spirits); spiritualism (here meaning an appeal to gods or communion with ancestor spirits); shamanism (the vesting of an individual with mystic powers); and divination (the supposed obtaining of truth by magic means), played a major role.

The practice of medicine developed gradually, and separately, in ancient Egypt, India, China, Greece, Persia and elsewhere. Medicine as it is practiced now developed largely in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century in England (William Harvey, seventeenth century), Germany (Rudolf Virchow) and France (Jean-Martin Charcot, Claude Bernard and others). The new, "scientific" medicine (where results are testable and repeatable) replaced early Western traditions of medicine, based on herbalism, the Greek "four humours" and other pre-modern theories.Template:Fact The focal points of development of clinical medicine shifted to the UK and the USA by the early 1900s (Canadian-born)Sir William Osler, Harvey Cushing). Possibly the major change in medical thinking was the gradual rejection in the 1400's of what may be called the 'traditional authority' approach to science and medicine. This was the notion that because some prominent person in the past said something must be so, then that was the way it was, and anything one observed to the contrary was an anomaly (which was paralleled by a similar shift in European society in general - see Copernicus's rejection of Ptolemy's theories on astronomy). People like Vesalius led the way in improving upon or indeed rejecting the theories of great authorities from the past such as Galen, Hippocrates, and Avicenna/Ibn Sina, all of whose theories were in time discredited.

Evidence-based medicine is a recent movement to establish the most effective algorithms of practice (ways of doing things) through the use of the scientific method and modern global information science by collating all the evidence and developing standard protocols which are then disseminated to doctors. One problem with this 'best practice' approach is that it could be seen to stifle novel approaches to treatment.

Practice of medicine

The practice of medicine combines both science as the evidence base and art, in the application of this medical knowledge in combination with intuition and clinical judgement to determine the treatment plan for each patient.

Central to medicine is the patient-doctor relationship, that begins when someone who is concerned about their health seeks a physician's help; the 'medical encounter'.

As part of the medical encounter, the doctor needs to:

- form a relationship with the patient

- gather data (medical history, systems enquiry, and physical examination, combined with laboratory or imaging studies (investigations))

- analyze and synthesize that data (assessment and/or differential diagnoses), and then:

- develop a treatment plan (further testing, therapy, watchful observation, referral and follow-up)

- treat the patient accordingly

- assess the progress of treatment and alter the plan as necessary (management).

The medical encounter is documented in a medical record, which is a legal document in many jurisdictions.[2] Other health professionals similarly establish a relationship with a patient and might perform various interventions, e.g. nurses, radiographers and therapists.

Health care delivery systems

Medicine is practiced within the medical system, which is a legal, credentialing and financing framework, established by a particular culture or government. The characteristics of the health care system have a very significant effect on the way that medical care is delivered.

Financing has a great influence as it defines who pays the costs. The most significant divide in developed countries is between universal health care and market-based health care (as practiced in the USA). Universal health care might allow or ban a parallel private market. The latter is described as single-payor system.

Transparency of information is another factor defining a delivery system. Access to information on conditions, treatments, quality and pricing greatly affects the choice by patients / consumers and therefore the incentives of medical professionals. While US health care system has come under fire for lack of openness, new legislation may encourage greater openness. There is a perceived tension between the need for transparency on the one hand and such issues as patient confidentiality and the possible exploitation of information for commercial gain on the other.

Health care delivery

Medical care delivery is classified into primary, secondary and tertiary care.

Primary care medical services are provided by physicians or other health professionals who has first contact with a patient seeking medical treatment or care. These occur in physician's office, clinics, nursing homes, schools, home visits and other places close to patients. About 90% of medical visits can be treated by the primary care provider. These include treatment of acute and chronic illnesses, preventive care and health education for all ages and both sex.

Secondary care medical services are provided by medical specialists in their offices or clinics or at local community hospitals for a patient referred by a primary care provider who first diagnosed or treated the patient. Referrals are made for those patients who required the expertise or procedures performed by specialists. These include both ambulatory care and inpatient services, emergency rooms, intensive care medicine, surgery services, physical therapy, labor and delivery, endoscopy units, diagnostic laboratory and medical imaging services, hospice centers, etc. Some primary care providers may also take care of hospitalized patients and deliver babies in a secondary care setting.

Tertiary care medical services are provided by specialist hospitals or regional centers equipped with diagnostic and treatment facilities not generally available at local hospitals. These include trauma centers, burn treatment centers, advanced neonatology unit services, organ transplants, high-risk pregnancy, radiation oncology, etc.

Modern medical care also depends on information - still delivered in many health care settings on paper records, but increasingly nowadays by electronic means.

Doctor-patient relationship

The doctor-patient relationship and interaction is a central process in the practice of medicine. There are many perspectives from which to understand and describe it.

An idealized physician's perspective, such as is taught in medical school, sees the core aspects of the process as the physician learning the patient's symptoms, concerns and values; in response the physician examines the patient, interprets the symptoms, and formulates a diagnosis to explain the symptoms and their cause to the patient and to propose a treatment. The job of a doctor is essentially to be a human biologist: that is, to know the human frame and situation in terms of normality. Once the doctor knows what is normal and can measure the patient against those norms the doctor can then determine the particular departure from the normal and the degree of departure. This is called the diagnosis.

The four great cornerstones of diagnostic medicine are anatomy (structure: what is there), physiology (how the structure/s work), pathology (what goes wrong with the anatomy and physiology) and psychology (mind and behaviour). In addition, the doctor should consider the patient in their 'well' context rather than simply as a walking medical condition. This means the socio-political context of the patient (family, work, stress, beliefs) should be assessed as it often offers vital clues to the patient's condition and further management. In more detail, the patient presents a set of complaints (the symptoms) to the doctor, who then obtains further information about the patient's symptoms, previous state of health, living conditions, and so forth. The physician then makes a review of systems (ROS) or systems enquiry, which is a set of ordered questions about each major body system in order: general (such as weight loss), endocrine, cardio-respiratory, etc. Next comes the actual physical examination; the findings are recorded, leading to a list of possible diagnoses. These will be in order of probability. The next task is to enlist the patient's agreement to a management plan, which will include treatment as well as plans for follow-up. Importantly, during this process the doctor educates the patient about the causes, progression, outcomes, and possible treatments of his ailments, as well as often providing advice for maintaining health. This teaching relationship is the basis of calling the physician doctor, which originally meant "teacher" in Latin. The patient-doctor relationship is additionally complicated by the patient's suffering (patient derives from the Latin patior, "suffer") and limited ability to relieve it on his/her own. The doctor's expertise comes from his knowledge of what is healthy and normal contrasted with knowledge and experience of other people who have suffered similar symptoms (unhealthy and abnormal), and the proven ability to relieve it with medicines (pharmacology) or other therapies about which the patient may initially have little knowledge.

The doctor-patient relationship can be analyzed from the perspective of ethical concerns, in terms of how well the goals of non-maleficence, beneficence, autonomy, and justice are achieved. Many other values and ethical issues can be added to these. In different societies, periods, and cultures, different values may be assigned different priorities. For example, in the last 30 years medical care in the Western World has increasingly emphasized patient autonomy in decision making.

The relationship and process can also be analyzed in terms of social power relationships (e.g., by Michel Foucault), or economic transactions. Physicians have been accorded gradually higher status and respect over the last century, and they have been entrusted with control of access to prescription medicines as a public health measure. This represents a concentration of power and carries both advantages and disadvantages to particular kinds of patients with particular kinds of conditions. A further twist has occurred in the last 25 years as costs of medical care have risen, and a third party (an insurance company or government agency) now often insists upon a share of decision-making power for a variety of reasons, reducing freedom of choice of both doctors and patients in many ways.

The quality of the patient-doctor relationship is important to both parties. The better the relationship in terms of mutual respect, knowledge, trust, shared values and perspectives about disease and life, and time available, the better will be the amount and quality of information about the patient's disease transferred in both directions, enhancing accuracy of diagnosis and increasing the patient's knowledge about the disease. Where such a relationship is poor the doctor's ability to make a full assessment is compromised and the patient is more likely to distrust the diagnosis and proposed treatment. In these circumstances and also in cases where there is genuine divergence of medical opinions, a second opinion from another doctor may be sought.

In some settings, e.g. the hospital ward, the patient-doctor relationship is much more complex, and many other people are involved when somebody is ill: relatives, neighbors, rescue specialists, nurses, technical personnel, social workers and others.

Clinical skills

A complete medical evaluation includes a medical history, a systems enquiry, a physical examination, appropriate laboratory or imaging studies, analysis of data and medical decision making to obtain diagnoses, and a treatment plan.[3]

The components of the medical history are:

- Chief complaint (CC): the reason for the current medical visit. These are the 'symptoms.' They are in the patient's own words and are recorded along with the duration of each one. Also called 'presenting complaint.'

- History of present illness / complaint (HPI): the chronological order of events of symptoms and further clarification of each symptom.

- Current activity: occupation, hobbies, what the patient actually does.

- Medications: what drugs the patient takes including over-the-counter, and home remedies, as well as herbal medicines/herbal remedies such as St. John's Wort. Allergies are recorded.

- Past medical history (PMH/PMHx): concurrent medical problems, past hospitalizations and operations, injuries, past infectious diseases and/or vaccinations, history of known allergies.

- Social history (SH): birthplace, residences, marital history, social and economic status, habits (including diet, medications, tobacco, alcohol).

- Family history (FH): listing of diseases in the family that may impact the patient. A family tree is sometimes used.

- Review of systems (ROS)or systems enquiry: an set of additional questions to ask which may be missed on HPI, generally following the body's main organ systems (heart, lungs, digestive tract, urinary tract, etc).

The physical examination is the examination of the patient looking for signs of disease ('Symptoms' are what the patient volunteers, 'signs' are what the doctor detects by examination). The doctor uses his senses of sight, hearing, touch, and sometimes smell (taste has been made redundant by the availability of modern lab tests). Four chief methods are used: inspection, palpation (feel), percussion (tap to determine resonance characteristics), and auscultation (listen); smelling may be useful (e.g. infection, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis). The clinical examination involves study of:

- Vital signs including height, weight, body temperature, blood pressure, pulse, respiration rate, hemoglobin oxygen saturation

- General appearance of the patient and specific indicators of disease (nutritional status, presence of jaundice, pallor or clubbing)

- Skin

- Head, eye, ear, nose, and throat (HEENT)

- Cardiovascular (heart and blood vessels)

- Respiratory (large airways and lungs)

- Abdomen and rectum

- Genitalia (and pregnancy if the patient is or could be pregnant)

- Musculoskeletal (spine and extremities)

- Neurological (consciousness, awareness, brain, cranial nerves, spinal cord and peripheral nerves)

- Psychiatric (orientation, mental state, evidence of abnormal perception or thought)

Laboratory and imaging studies results might be obtained, if necessary.

The medical decision-making (MDM) process involves analysis and synthesis of all the above data to come up with a list of possible diagnoses (the differential diagnoses), along with an idea of what needs to be done to obtain a definitive diagnosis that would explain the patient's problem.

The treatment plan might include ordering additional laboratory tests and studies, starting therapy, referral to a specialist, or watchful observation. Follow-up may be advised.

This process is used by primary care providers as well as specialists. It may take only a few minutes if the problem is simple and straightforward, but it may take weeks in a patient who has been hospitalized with unusual symptoms or multi-system problems, with involvement of several specialists.

On subsequent visits, the process may be repeated in an abbreviated manner to obtain any new history, symptoms, physical findings, and lab or imaging results or specialist consultations.

Diagnostic specialties

- Pathology is the branch of medicine that deals with the study of diseases and the morphologic, physiologic changes produced by them. As a diagnostic specialty, pathology can be considered the basis of modern scientific medical knowledge and plays a large rôle in evidence-based medicine. Many modern molecular tests such as flow cytometry, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, gene rearragements studies and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) are usedin with by pathologists.

- Radiology is concerned with imaging of the human body, e.g. by x-rays, x-ray computed tomography, ultrasonography, and nuclear magnetic resonance tomography.

Clinical specialties

- Anesthesiology (AE) or anaesthesia (BE) is the clinical discipline concerned with providing anesthesia.

- Dermatology is concerned with the skin and its diseases. In the UK, dermatology is a subspeciality of general medicine.

- Emergency medicine is concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of acute or life-threatening conditions, including trauma, surgical, medical, pediatric, and psychiatric emergencies.

- General practice, family practice, family medicine or primary care is, in many countries, the first port-of-call for patients with non-emergency medical problems. Family doctors are usually able to treat over 90% of all complaints without referring to specialists.

- Hospital medicine is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Doctors whose primary professional focus is hospital medicine are called hospitalists in the USA.

- Internal medicine is concerned with systemic diseases of adults, i.e. those diseases that affect the body as a whole (restrictive, current meaning), or with all adult non-operative somatic medicine (traditional, inclusive meaning), thus excluding pediatrics, surgery, gynecology and obstetrics, and psychiatry. There are several subdisciplines of internal medicine:

- Medical genetics is concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of inherited diseases.

- Neurology is concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of nervous system diseases. It is a subspeciality of general medicine in the UK.

- Obstetrics and gynecology (often abbreviated as Ob/Gyn) are concerned respectively with childbirth and the female reproductive and associated organs. Reproductive medicine and fertility medicine are generally practiced by gynecological specialists.

- Pain medicine is a sub-speciality of a number of fields (e.g. General practice, Anaesthesia, Neurosurgery, Internal Medicine), devoted to the study and treatment of acute and chronic pain in patients with or without cancer.

- Palliative care is a relatively modern branch of clinical medicine that deals with pain and symptom relief and emotional support in patients with terminal illnesses including cancer and heart failure.

- Pediatrics (AE) or paediatrics (BE) is devoted to the care of infants, children, and adolescents. Like internal medicine, there are many pediatric subspecialities for specific age ranges, organ systems, disease classes, and sites of care delivery. Most subspecialities of adult medicine have a pediatric equivalent such as pediatric cardiology, pediatric endocrinology, pediatric gastroenterology, pediatric hematology, pediatric oncology, pediatric ophthalmology, and neonatology.

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation (or physiatry) is concerned with functional improvement after injury, illness, or congenital disorders.

- Preventive medicine is the branch of medicine concerned with preventing disease.

- Psychiatry is the branch of medicine concerned with the bio-psycho-social study of the etiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cognitive, perceptual, emotional and behavioral disorders. Related non-medical fields include psychotherapy and clinical psychology.

- Radiation therapy is concerned with the therapeutic use of ionizing radiation and high energy elementary particle beams in patient treatment.

- Radiology is concerned with the interpretation of imaging modalities including x-rays, ultrasound, radioisotopes, and MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). A newer branch of radiology, interventional radiology, is concerned with using medical devices to access areas of the body with minimally invasive techniques.

- Surgical specialties employ operative treatment. These include Orthopedics, Urology, Ophthalmology, Neurosurgery, Plastic Surgery, Otolaryngology and various subspecialties such as transplant and cardiothoracic. Some disciplines are highly specialized and are often not considered subdisciplines of surgery, although their naming might suggest so.

- Urgent care focuses on delivery of unscheduled, walk-in care outside of the hospital emergency department for injuries and illnesses that are not severe enough to require care in an emergency department.

- Gender-based medicine studies the biological and physiological differences between the human sexes and how that affects differences in disease.

Medical education

Medical education is education related to the practice of being a medical practitioner, either the initial training to become a doctor or further training thereafter.

Medical education and training varies considerably across the world, however typically involves entry level education at a university medical school, followed by a period of supervised practise (Internship and/or Residency) and possibly postgraduate vocational training. Continuing medical education is a requirement of many regulatory authorities.

Various teaching methodologies have been utilised in medical education, which is an active area of educational research.

Legal restrictions

In most countries, it is a legal requirement for medical doctors to be licensed or registered. In general, this entails a medical degree from a university and accreditation by a medical board or an equivalent national organization, which may ask the applicant to pass exams. This restricts the considerable legal authority of the medical profession to doctors that are trained and qualified by national standards. It is also intended as an assurance to patients and as a safeguard against charlatans that practice inadequate medicine for personal gain. While the laws generally require medical doctors to be trained in "evidence based", Western, or Hippocratic Medicine, they are not intended to discourage different paradigms of health and healing, such as alternative medicine or faith healing.

Criticism

Criticism of medicine has a long history. In the Middle Ages, some people did not consider it a profession suitable for Christians, as disease was often considered God sent. God was considered to be the 'divine physician' who sent illness or healing depending on his will. However many monastic orders, particularly the Benedictines, considered the care of the sick as their chief work of mercy. Barber-surgeons (they had the sharpest knives) generally had a bad reputation that was not to improve until the development of academic surgery as a speciality of medicine, rather than an accessory field.

Through the course of the twentieth century, doctors focused increasingly on the technology that was enabling them to make dramatic improvements in patients' health. The ensuing development of a more mechanistic, detached practice, with the perception of an attendant loss of patient-focused care, known as the medical model of health, led to further criticisms. This issue started to reach collective professional consciousness in the 1970s and the profession had begun to respond by the 1980s and 1990s.

Perhaps the most devastating criticism of modern medicine came from Ivan Illich. In his 1976 work Medical Nemesis, Illich stated that modern medicine only medicalises disease and causes loss of health and wellness, while generally failing to restore health by eliminating disease. This medicalisation of disease forces the human to become a lifelong patient.[4]Other less radical philosophers have voiced similar views, but none were as virulent as Illich. Another example can be found in Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology by Neil Postman, 1992, which criticises overreliance on technological means in medicine.

See also

- Big killers

- Branches of medicine

- Complementary and alternative medicine

- Diagnosis

- Health

- Health care

- Health profession

- Health care system

- Iatrogenesis (ill health caused by medical treatment)

- Life extension

- List of diseases

- List of disorders

- List of medical abbreviations

- List of medical roots

- List of medical schools

- Important publications in medicine

- Medical equipment

- Naturopathic Medicine

- Pharmaceutical company

- Potassium in Nutrition and Human Health

- Rare diseases

References

- ↑ Loriaux, D Lynn MD, PhD Aristotle (384-322 BC). Endocrinologist. 15(4):197-198, July/August 2005

- ↑ AHIMA e-HIM Work Group on the Legal Health Record. (2005). "Update: Guidelines for Defining the Legal Health Record for Disclosure Purposes.". Journal of AHIMA 78 (8): 64A–G.

- ↑ Coulehan JL, Block MR (2005). The Medical Interview: Mastering Skills for Clinical Practice, 5th ed.. F. A. Davis. ISBN 0-8036-1246-X.

- ↑ Ivan Illich (1976). Medical Nemesis. ISBN 0-394-71245-5 ISBN 0-7145-1095-5 ISBN 0-7145-1096-3.

External links

- NLM (US National Library of Medicine, contains resources for patients and health care professionals)

- Online UK Medical Dictionary

- eMedicine Physician contributed medical articles and CME

- New Media Medicine Discussion forum for medical professionals

- PLoS Medicine Open-access medical journal

- Medicine News Latest Medicine News