Vietnam wars

There have been two millennia of Vietnam wars in the region now called Vietnam.[1] Beginning with the Trung Sisters' revolt against China in the first century CE, this area of Southeast Asia has seen civil wars (during the creation of the Nguyen Dynasty in (1789-1802) and cautious cooperation with French missionaries, resistance to the French colonization (beginning in 1858). In addition to what the West calls the Vietnam War, there have been several other savage 20th-century wars in the region.

This is the top-level article for numerous articles about an extremely complex situation over a significant period of time.

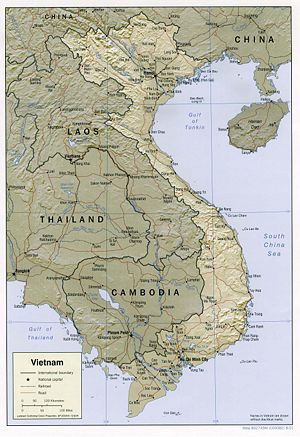

Subarticles may not be in chronological such as Vietnamese Communist grand strategy, for events below these and other major events between 1868 and 1999. Some related articles are not strictly subordinate, such as Dai Viet and Nguyen Dynasty for earlier history. Also see Vietnam and Southeast Asia for more geographic coverage. |

The 20th century conflicts began with nationalist resistance to the French, and continued through the events of the Second World War, that became the Indochinese revolution (1946-1954) against the French[2], low-level civil war between the two Vietnams after the Geneva Accords (1954-1962), with substantial activity in Laos; the widespread conflict during the deployment of American forces in the (1962-1972) period; the independent ground combat by South Vietnam and its fall (1972-1975) and what has been called the Third Indochina War (1978-1999), involving Vietnam, Cambodia, China, and Thailand. This article puts all of these wars, not just those involving the U.S. or the Cold War, into a broader historical context, with an emphasis on how the wars affected Vietnam, the Vietnamese, and the region of Southeast Asia.

There were at least two periods of hot modern war, first the Indochinese revolution, starting with guerrilla resistance before the Second World War and ending in a 1954 Geneva treaty that partitioned the country into the Communist North (NVN) (Democratic Republic of Vietnam, DRV) and non-Communist South (SVN) (Republic of Vietnam, RVN). A referendum on reunification had been scheduled for 1956, but never took place. Nevertheless, a complex and powerful United States Mission to the Republic of Vietnam was always present after the French had left and the Republic of Vietnam established.

Cold War events in Vietnam had several phases, beginning with the Communist-dominated national coalition effort to oust the French colonial government after World War II. After the First Indochinese War, North Vietnam made the policy decision to invade the South and began, surreptitiously to prepare. U.S. advisers had been present in the South since 1955, but they began to accompany South Vietnamese combat troops in 1962. The U.S.A. became more and more involved in South Vietnam, with the advisory buildup (1962-1964), the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964, the U.S. ground combat involvement (1964-1972); and South Vietnam fighting its own ground war (1972-1975).

Three years after the U.S. withdrawal, South Vietnam collapsed after being invaded by the DRV in 1975, and the two halves were united. The televised images of the T-54 tanks that broke down the gates of the Presidential Palace in the southern capital, Saigon, broadcast around the world, seemed to announce the defeat of American military might. Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City, and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam replaced North and South Vietnam. But although Vietnam was now unified under a Communist government, this did not end the fighting. After small-scale fighting since 1973, Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1978, was twice invaded by China in 1979 and 1984, and with the last Cambodian resistance ending in 1999. "Vietnam" has become synonymous with long conflicts; some cynics have called the Cambodian involvement "Vietnam's Vietnam."

While the country remains officially Communist, in 1986, the Vietnamese introduced market reforms and began to participate in the international economic system, under a system called doi moi.

Background

French missionaries had been active in Southeast Asia since at least 1802, helping Emperor Gia Long reestablish the Nguyen Dynasty. In 1858, France invaded the region, and the Nguyen Emperor accepted protectorate status for the four parts of what is now Vietnam. These included Cochin China in the south (which encompassed the Mekong River Delta and its major city Gia Dinh, Saigon, and Ho Chi Minh City), Annam in the center (and its major city Hue), the mountainous Central Highlands, and Tonkin in the North (which encompassed the Red River Delta, and the major cities of Hanoi and Haiphong). This colony became known as French Indochina. French forces took until June 1867 to complete their takeover of the area. The provinces of Cochin China were the last to fall. In July 1867, the government of neighboring Siam (now Thailand) accepted the Cambodian protectorate in return for the two Cambodian provinces of Angkor and Battambang. Siam itself never came under colonial rule. In 1870, after the Emperor Napoleon III fell from power, French colonial officers intensified their focus on Indochina.[3]

In the 1920s and 1930s, both non-Communist and Communist nationalist groups were developing in French Indochina. As the Japanese expansion in China became evident, France began to suppress resistance to French rule within IndoChina, hoping to unite the colony in resistance to further Japanese expansion. Once France fell to Nazi Germany in World War II, the colony was given to Japan as a protectorate in two stages. First, Japan was given control over the cities of Hanoi and Saigon in the summer of 1940. Japan took over the entirety of the colony the following year. French Indochina was not a major theater of operations during the Second World War and was returned to French control following the surrender of Japan in 1945.

Vietnam's climate has a major effect on warfare, especially involving vehicles and aircraft. Major operations usually took place in the dry season. While the most southern parts tend to have a generally tropical climate, there are two major climactic periods:

- Monsoon season of heat, rain, and mud, with limited mobility (May to September)

- Warm and dry conditions (October to March)

Geostrategic Perspective

Andrew Wiest points out that the conflicts in Vietnam can be viewed at multiple levels: as ideological struggles, civil war, regional conflict within either Indochina or the broader Southeast Asian region, or as a part of the Cold War[4] In reality they were a combination of all of these. Michael Lind, who regarded the U.S. involvement as necessary, speaks of the period "between two wars" as one in which the North

followed the advice of Mao's government and concentrated on consolidating its rule rather than on sponsoring revolution in South Vietnam...[while] Ngo Dinh Diem was using force and fraud to cobble together a state in the southern half of Vietnam[5]

In the West, the 1962-1975 "Vietnam War" is primarily considered as a part of the Cold War. Before that, there were wars of colonialism and nationalist resistance to it. Colonialism was not limited to the Third French Republic, but to a long history of Chinese attempts to control the region. Vietnamese nationalism is not something new, but unfortunately this was often not realized in other countries.

While Vietnamese Communists had long had aims to control the whole of Vietnam, the specific decision to conquer the South was made, by the Northern leadership, in May 1959.[6] The Communist side had clearly defined political objectives, and a grand strategy to achieve them; there was a clear relationship between long-term goals and short-term actions, within their strategic theory of dau trinh. Some of their actions may seem to be from Maoist and other models, but they have some unique concepts that are not always obvious.

Vietnamese Communist activity has to be considered, early on, in the conflict between Josef Stalin and Leon Trotsky and their respective priorities; in the Sino-Soviet conflict; and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Each caused internal Vietnamese factions to gain or lose influence.

Apart from its internal problems, South Vietnam faced difficult military challenges. On the one hand, there was a threat of a conventional, cross-border strike from the North, reminiscent of the Korean War. In the 1950s, the U.S. advisors focused on building a "mirror image" of the U.S. Army, designed to meet and defeat a conventional invasion. [7] Ironically, while the lack of counterguerrilla forces threatened the South for many years, the last two blows were Korea-style invasions. With U.S. air support, the South were able to largely repel a conventional invasion by North Vietnam. The 1975 invasion which defeated the South was not opposed by U.S. forces.

First French-Indochina War (1946-1954)

While there is no universally agreed name for this period in the history of Vietnam, it is the period between the formation of a quasi-autonomous government within the French Union, and the the eventual armed defeat of the French colonial forces by the Viet-Minh. That defeat led to the 1954 Geneva accords that split Vietnam into North and South.

The French first created a provisional government under the last Nguyen Emperor, Bao Dai, then recognized Vietnam as a state within the French Union. In such a status, France would still control the foreign and military policy of Vietnam, which was unacceptable to both Communist and non-Communist nationalists.

The "Vietnam War" (1957-1975)

<This whole section should be condensed to a few paragraphs. The text itself should be moved and integrated into appropriate sections in the Vietnam War article or other appropriate subpages.>

This period began with the military defeat of the French in 1954, and a subsequent meeting at Geneva that partitioned Vietnam into two countries - North and South.The French defeat occurred in many places, but is often known by the name of the most famous engagement: the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. Two of the provisions of the Geneva agreement were never fulfilled: the agreement proposed that a referendum on unification should be held in 1956, and also banned foreign military support and intervention. Neither the Communist side nor the Diem government wanted the referendum. It is sometimes called the beginning of the Second Indochinese War, although others use that term to describe the start of U.S. combat involvement. The North Vietnamese have referred to it as the American War.[8]

It has been argued, certainly with some justification, that the U.S. unwisely supported the French before 1954, and still had a pro-French view after 1954. Part of this was due to U.S. diplomatic strategy that saw French cooperation in Europe as essential to NATO and to Western stability, and taking a pro-French position in the former Indochina obtained cooperation from France. The Vietnamese were not seen as important, in Cold War terms, in the 1940s and 1950s, even though, perhaps ironically, it was Japanese expansion into French Indochina that triggered U.S. economic warfare against Japan, and eventually the Japanese decision for war in 1941.

Later, the U.S. would support anticommunist Vietnamese, never neutralists.

Partition

- See also: Government of the Republic of Vietnam

Between the 1954 Geneva accords and 1956, the two countries were still forming, under the influence of major powers, especially France and the U.S.A., and to a lesser extent China and the Soviet Union. In the south, the Diem government was unpopular, but there was no obvious alternative that would rise above factionalism, and also gain external support. Anti-Diem movements were not always Communist, although some were. Diem had his own authoritarian philosophy with mixed Confucian, French, and Vietnamese roots, and was not open to the idea of an opposition. Ho probably would have won an election, but free elections were alien concepts, and they wanted to keep control, not throw the dice on the reaction of the people. By 1955, the bulk of Diem's military advice and funding was coming from the U.S.A., which justified its involvement as part of the containment policy of Communism. There was concern that the Chinese might intervene as they had done in the Korean War.

The situation reflected not only 'jockeying for power', but also the fact that the province chief had security authority that could conflict with that of tactical military operations in progress, but also had responsibility for the civil administration of the province. That civil administration function became more and more intertwined, starting in 1964 and accelerating in 1966, with the "other war" of rural development.[9]

The North was exploring its policy choices, both in terms of the South, and its relations with China and the Soviet Union. The priorities of the latter were not necessarily those of Ho, just as U.S. and French priorities were not necessarily those of Diem.

In 1957-1958, there was a guerrilla movement against the Diem government, involving assassinations, expropriations, recruiting, shadow government, and other things characteristic of Mao's Phase I. The guerrillas were primarily native to the south or had been there for some time. While there was communication with, and perhaps arms supply from, the north, there is little evidence that there were any Northern units in the South, although some organizers may have infiltrated. In 1959, North Vietnam decided to overthrow the South by military means. Originally, the military means were guerrilla warfare, carried out by the Viet Cong, or the military arm of the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF). While the eventual fall of South Vietnam would be due to conventional rather than guerrilla warfare, some authors, such as Bui Tin, assert that the NLF was never an indigenous Southern force but always under the control of the North. [10]

Pacification

After partition, there was a continuing struggle for security of the rural population, and to win their support for the government. A convenient general term for the many programs involved is pacification in South Vietnam. It has also been called the "Other War" or "Second War" to differentiate it from direct combat with Communist military forces in the South, although some refer to a "Third War" against Communists outside the South. This began under the Diem government, and went by many names as the U.S. became more deeply involved.

Some kind of Viet Minh-derived organization remained in the South between 1954 and 1960, but it is unclear that they were directed to take over action until 1957 or later. Before then, they were recruiting and building infrastructure, a basic first step in a Maoist protracted war mode.

While the visible guerrilla incidents increased gradually, the key policy decisions by the North were made in 1959. Early in this period, there was more conflict in Laos than in South Vietnam. U.S. combat involvement was, at first, greater in Laos, but the activity of advisors, and increasingly U.S. direct support to South Vietnamese soldiers, increased, under U.S. military authority, in late 1959 and early 1960. Communications intercepts in 1959, for example, confirmed the start of the Ho Chi Minh trail and other preparation for large-scale fighting.

U.S. advisory and support role

The original U.S. involvement, before the Second World War, was complex; the U.S. supported China against Japan, and was concerned that Vichy French cooperation with the Japanese would assist the Japanese in China. U.S. embargoes on shipments to Japan were conditional on Japan withdrawing from French Indochina; Japanese unwillingness to do so led fairly directly to attacking Pearl Harbor.U.S. involvement in the region began with intelligence collection in the Second World War.

During the Second World War, the U.S. primarily observed from the China-Burma-India theater. After the Japanese surrender, while British forces released French forces from Japanese prisons, enabling them to take control, the U.S. involvement stayed on a diplomatic and intelligence level until 1950.

As soon as the Second World War ended, Harry S. Truman was under great pressure to return the country to normal civilian conditions, and he demobilized rapidly to release funds for domestic spending. There were no such pressures to demobilize, however, on Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong. There was internal argument, within the United States Government, between 1945 and 1950, about the appropriate role of the U.S. in East and Southeast Asia.

American involvement in Indochina restarted in 1950, more as a consequence of the fall of the Nationalist Chinese. Truman has been blamed for "losing" Eastern Europe and China, but it is less clear what could have been done to stop it. The decision to cut military commitment came home to roost in the Korean War, when Truman had few forces to dispatch.

When Dwight D. Eisenhower succeeded Truman as President in 1952, after a campaign that had attacked Truman's "weaknesses" against communism and in Korea, he formulated a strong policy of containing Communism, but his administration did not regard Southeast Asia as critical. Eisenhower personally rejected the proposal, from Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to the Operation Vulture proposal to give air support to the French at Dien Bien Phu. After the fall of the French in 1954-1955, the U.S. took over the previous French role of training the now-South Vietnamese military.

Communism has been called a "secular religion", and the North Vietnamese officials responsible for psychological warfare, as well as military operations, were part of a system of dau trinh or "struggle" doctrine. Communism, for its converts, was an organizing belief system that had no equivalent in the South. At best, the southern leadership wanted a prosperous nation, but too often they were focused on personal prosperity. Their Communist counterparts, however, had a mission of conversion by the sword — or the AK-47 assault rifle.

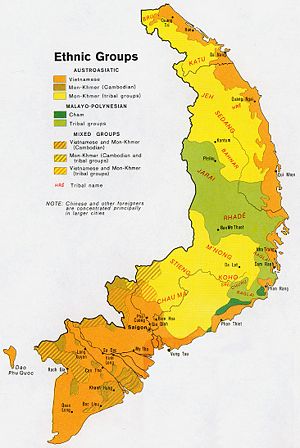

Guerrilla attacks increased in the early 1960s, at the same time as the new John F. Kennedy administration made Presidential decisions to increase its influence. Diem, as other powers were deciding their policies, was facing disorganized attacks and internal political dissent. There were conflicts between the government, dominated by minority Northern Catholics, and both the majority Buddhists and minorities such as the Montagnards, Cao Dai, and Hoa Hao. These conflicts were exploited, initially at the level of propaganda and recruiting, by stay-behind Viet Minh receiving orders from the North.

South Vietnamese government

After the French colonial authority ended, Vietnam was ruled by a nominally civilian government, led by first Bao Dai and then, from 1954, by Ngo Dinh Diem; neither were elected. In November 1963, Diem was killed in a military coup and he was replaced by a nominal civilian government really under military control, which was overthrown by yet another military coup (involving some of the same generals) in January 1964. After a period of overt military government, there was a gradual transition to at least the appearance of democratic government, but South Vietnam neither developed a true popular government, nor rooted out the corruption that caused a lack of support.

Between 1964 and 1967 there was a constant struggle for power in South Vietnem, and not just from within the military. Several Buddhist and other factions often derived from religious sects, which became involved in the jockeying for political power, such as the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao. Even the Vietnamese Buddhists were not monolithic, and had their own internal struggles. At varying times, sects, organized crime such as the Binh Xuyen, and individual provincial leaders had paramilitary groups that affected the political process; while the Montagnard ethnic groups wanted autonomy for their region. William Colby (then chief of the Central Intelligence Agency Far Eastern Division) observed that civilian politicians "divided and sub-divided into a tangle of contesting ambitions and claims and claims to power and participation in the government." [11] Some of these factions sought political power or wealth, while others sought to avoid domination by other groups (Catholic vs Buddhist in the Diem Coup).

Vietnamese and U.S. goals were also not always in complete agreement. Until 1969, the U.S.A. was generally anything opposed to any policy, nationalist or not, which might lead to the South Vietnamese becoming neutralist rather than anticommunist. The Cold War containment policy was in force through the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson Administrations, while the Nixon administration supported a more multipolar model of detente.

While there were still power struggles and internal corruption, there was much more stability between 1967 and 1975. Still, the South Vietnamese government did not enjoy either widespread popular support, or even an enforced social model of a Communist state. It is much easier to disrupt a state without common popular or decision maker goals.

U.S. covert operations

- See also: MACV-SOG

- See also: CIA activities in Vietnam

- See also: Air campaigns against Cambodia and Laos

Covert military assistance and operations were never uniquely American. During the Indochinese Revolution, the Soviets and Chinese advised and supplied the Viet Minh; there were Chinese artillerymen bringing in heavy rocket launchers in the final assault on Dien Bien Phu. U.S. transport aircraft, operated by a CIA proprietary airline, supported the French, including with airdrops at Dien Bien Phu.

As French control waned in 1954, there had been a CIA program, the Saigon Military Mission under Edward Lansdale to put Vietnamese guerrillas in the north during partition.

The first covert action teams including U.S. military to take to the field, in the region, were in Laos, not Vietnam; the teams were originally military personnel detailed to the CIA, although the military involvement became somewhat more overt as an advisory group in 1961, before the cease-fire. It was a complex situation in Laos, with various shifting alliances, military coups, and an eventual neutralization. President Kennedy chose principally diplomatic and covert means in Laos; "having determined if there was to be a war, it ought to be in Vietnam." By no means was the U.S. the only foreign power involved in Laos; the Soviet Union and North Vietnam supported the Communist Pathet Lao. U.S. covert operators entered into a long-term relationship with Hmong Montagnards in Laos, who favored neither the Lao government nor the Pathet Lao. [12]

A continuing reason for the U.S. involvement in Laos was surveillance, and limited interference, with operations on the Ho Chi Minh, which greatly increased during the active Vietnam War. South Vietnamese covert operators in the Nha Ky Thuat and separate observation groups also operated, with CIA cooperation, from South Vietnam into Laos.

Western combat role begins

Other than in covert operations, U.S. advisers started to accompany ground combat missions, as well as participate in combat support, in 1962, during the Kennedy Administration. The first American to die was a soldier accompanying an ARVN team on a communications intelligence mission, doing direction finding on the Viet Cong.

It should be noted that Australia joined the 1962 advisory effort. Australian motivation was complex; it was less due to Australian support of U.S. policies in Vietnam, and more to ensure that the U.S. would continue to support Australia against Indonesia in their regional conflict beginning in 1961. The U.S. had supported an Indonesian claim over West New Guinea, and had told he Australian government that the hostilities in Borneo was insufficient to invoke the ANZUS (Australia-New Zealand-United States) mutual defense guarantee. Subsequent involvement by New Zealand related to its policy of keeping its foreign policies aligned with that of Australia. While their participation was excellent, it was far more closely associated with ANZUS relations than with the specific concern of those states with Vietnam.[13] The small but distinguished Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV) was highly effective and one of the most decorated units in Australian history. [14] During the later ground combat phases, Australian troops in brigade strength, along with naval and air forces, participated in the larger war.

While there had been some covert bombing and ground reconnaissance, especially in Laos, before the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964, that event marked the beginning of overt U.S. combat. President Lyndon B. Johnson asked for, and received, Congressional authority to use military force in Vietnam after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which was described as a North Vietnamese attack on U.S. warships. After much declassification and study, much of the incident remains shrouded in what Clausewitz has called the "fog of war", but questions have been raised about whether the North Vietnamese believed they were under attack, about who fired the first shots, and, indeed, if there was a true attack.

The initial actions were retaliatory air raids against the North. Additional responses came, at first, as retaliations for specific Viet Cong actions in the South. There was considerable discussion, inside the U.S. government, about the risks and benefits of various air operations against North Vietnam. Operation Rolling Thunder, the eventual model created, and used through 1968, was a graduated pressure rather than an intense attack. While 1972 air operations of much greater intensity had much more effect, both the type of targets and the technology available to attack them in 1964 was much different than in 1972. During Rolling Thunder and other air operations against the Ho Chi Minh trail, airpower was of limited effect in stopping the logistics of a guerrilla war; the attacks in 1972 did stop the logistics of a conventional invasion. 1972 saw the early use of precision-guided munitions, although of much lesser capability than those used in Operation Desert Storm and subsequent campaigns.

The greatest U.S. involvement was from mid-1964 through 1972, with some activity on both ends. So, much of the detailed U.S. political action with other countries will be in Joint warfare in South Vietnam 1964-1968, Vietnamization, and air operations against North Vietnam. It is not practical to draw a hard-and-fast line. Many, but by no means all, of the key political decisions were under Johnson, but Presidents from Truman through Ford all had roles.

Increasing involvement

JFK and his key staff, came from a different elite than that which had spawned John Foster Dulles, but, while the form was different, a militant anti-Communism was underneath many of the Kennedy Administration policies. [15] Its rougher operatives had a different style than Joe McCarthy, but it is sometimes forgotten that Robert Kennedy (RFK) had been on McCarthy's staff. [16] Where Republicans during the Truman and Eisenhower administrations blamed Democrats who had "lost China", the Kennedy Administration was not out to lose anything; there was no major commitment to Southeast Asia.

Under Kennedy, U.S. advisers started going with ARVN forces on combat operations, and providing combat support such as intelligence and airlift. The first American soldier to die in combat in Vietnam was a signals intelligence technician on a direction-finding mission, caught in an ambush.

Johnson's motives were different from Kennedy's, just as Nixon's motivations would be different from Johnson's. Of the three, Johnson was most concerned with U.S. domestic policy, with protecting his 'domestic legacy'. Karnow quotes his comment to his biographer, Doris Kearns, as

"I knew from the start that I was bound to be crucified either way I moved. If I left the woman I really loved — the Great Society — in order to get involved with that bitch of a war on the other side of the world, then i would lose everything at home. All my programs. All my hopes to feed the hungry and shelter the homeless. All my dreams to provide education and medical care to the browns and the blacks and the lame and the poor. But if I left that war and let the Communists take over South Vietnam, I would be seen as a coward and my nation seen as an appeaser, and we would both find it impossible to accomplish anything for anybody anywhere on the entire globe."[17]

The beginning of large-scale combat

Under the Johnson Administration, the Gulf of Tonkin incident took place, for which he ordered immediate retaliatory airstrikes, and then sought and received the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution from the Congress. The United States never actually declared war for the conflict that it fought longest.

He judged actions in Vietnam not only on their own merits, but how they would be perceived in the U.S. political system. [18] To Johnson, Vietnam was a "political war" only in the sense of U.S. domestic politics, not a political settlement for the Vietnamese. He also saw it political in the sense of both his personal, and the U.S., position vis-a-vis the rest of the world. In that context, Johnson, on April 23, 1964, gave a press conference, followed by a diplomatic initiative, [19]for what was called a "many flags" effort for assistance by traditional U.S. allies. Wherever possible, the many flags approach was used to downplay the image of the U.S. fighting a small country, [20] although North Vietnam, the Soviet Union, and China hardly were neutrals. For the first time, Australia and New Zealand joined U.S. troops in battle without British participation. [21] Eventually, troops from Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Korea, and Thailand, sometimes with their costs paid by the United States, joined the U.S. and South Vietnamese operations.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who had been appointed by Kennedy, became Johnson's principal adviser, and continued to push an economic and signaling grand strategy. Johnson and McNamara, although it would be hard to find two men of more different personality, formed a quick bond. McNamara appeared more impressed by economics and Schelling's compellence theory [22] than by Johnson's liberalism or Senate-style deal-making, but they agreed in broad policy. [23]

They directed a plan for South Vietnam that they believed would end the war quickly. Note that the initiative was coming from Washington; the unstable South Vietnamese government was not part of defining their national destiny. The plan selected was from GEN William Westmoreland, the field commander in Vietnam. Opposition against Johnson peaked in 1968; see Tet Offensive. On March 31, 1968, Johnson said on national television,

"I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president"

Vietnamization and seeking negotiations

In March, Johnson had also announced a bombing halt, in the interests of starting talks. The first discussions were limited to starting broader talks, as a quid-pro-quo for a bombing halt.:[24]

During the 1968 Presidential campaign, a random wire service story headlined that Nixon had a "secret plan for ending the war, but, in reality, Nixon was only considering alternatives at this point. He remembered how Eisenhower had deliberately leaked, to the Communist side in the Korean War, that he might be considering using nuclear weapons to break the deadlock. Nixon adapted this into what he termed the "Madman Strategy".[25]

After the election of Richard M. Nixon, a review of U.S. policy in Vietnam was the first item on the national security agenda. Henry Kissinger, the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, asked all relevant agencies to respond with their assessment, which they did on March 14, 1969.[26]

Withdrawal of ground troops

While Nixon hesitated to authorize a military request to bomb Cambodian sanctuaries, which civilian analysts considered less important than Laos, he authorized, in March, bombing of Cambodia as a signal to the North Vietnamese. While direct attack against North Vietnam, as was later done in Operation Linebacker I, might be more effective, he authorized the Operation MENU bombing of Cambodia, starting on March 17.

U.S. policy changed to one of turning ground combat over to South Vietnam, a process called Vietnamization, a term coined in January 1969. Nixon, in contrast, saw resolution not just in Indochina, in a wider scope. He sought Soviet support, saying that if the Soviet Union helped bring the war to an honorable conclusion, the U.S. would "do something dramatic" to improve U.S.-Soviet relations. [24] In worldwide terms, Vietnamization replaced the earlier containment policy[27] with detente.[28]

Allied ground troops depart

In the transition to full "Vietnamization," U.S. and third country ground troops turned ground combat responsibility to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Air and naval combat, combat support, and combat service support from the U.S. continued. While the ARVN improved in local security and small operations, Operation Lam Son 719, in February 1971, the first large operation with only ARVN ground forces, they took casualties that the South Vietnamese leadership considered unacceptable, and withdrew. This operation still had U.S. helicopters lifting the crews, and U.S. intelligence and artillery support. By 1972, however, under the "many flags" program, there were more South Korean than U.S. ground troops in South Vietnam.[20]

South Vietnamese troops did much better against the 1972 Eastertide invasion, but this still involved extensive U.S. air support. To help the ARVN stop this invasion, Nixon launched Operation Linebacker I, with the operational goal of disabling the infrastructure of infiltration. One of the problems of the Republic of Vietnam's Air Force is that it never operated under central control, even for a specific maximum-effort air offensive. South Vietnamese aircraft always were controlled by regional corps commanders, so never developed skills in deep battlefield air interdiction. It was not only U.S. capability, but U.S. doctrine that let it interrupt the flow of supplies to the invasion force before it entered combat.

When the North refused to return to negotiations in late 1972, Nixon, in mid-December, ordered bombing at an unprecedented level of intensity, Operation Linebacker II. This was at the strategic and grand strategic levels, attacking not so much the infiltration infrastructure, but North Vietnam's ability to import supplies, its internal transportation and logistics, command and control, and integrated air defense system. Within a month of the start of the operation, a peace agreement was signed.

The last Australian AATTV advisers left in January 1973. [29]

Peace accords and forcible unification, 1973-75

Peace accords were finally signed on 27 January 1973, in Paris. U.S combat troops immediately began withdrawal, and prisoners of war were repatriated. U.S. supplies and limited advise could continue. In theory, North Vietnam would not reinforce its troops in the south.

The North, badly damaged by the bombings of 1972, recovered quickly and remained committed to the destruction of its rival. There was little U.S. popular support for new combat involvement, and no Congressional authorizations to expend funds to do so. When Gerald Ford, Nixon's final vice-president, succeeded Nixon, most major policies had been set by the time he took office. He was under a firm Congressional and public mandate to withdraw.North Vietnam launched a new conventional invasion in 1975 and seized Saigon on April 30.[30]

Final U.S. evacuation

No American combat units were present until the final days, when Operation FREQUENT WIND was launched to evacuate Americans and 5600 senior Vietnamese government and military officials, and employees of the U.S. The 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade, under the tactical command of Alfred M. Gray, Jr., would enter Saigon to evacuate the last Americans from the American Embassy to ships of the Seventh Fleet. Ambassador Graham Martin was among the last civilians to leave. [31] In parallel, Operation Eagle Pull evacuated U.S. and friendly personnel from Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on April 12, 1975, under the protection of the 31st Marine Amphibious Unit, part of III MAF.

Vietnam was unified under Communist rule, as nearly a million refugees escaped by boat. Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

A new perspective for Vietnam

Certainly, Vietnamese leaders demonstrated the ability to think on complex strategic levels. It is someone ironic, then, that they seemed to repeat some of the conflicts of the French and Americans.

France, and then the U.S., had claimed a "special relationship" with Vietnam, but Vietnam claimed a "special relationship" with Laos and Cambodia. Essentially, Vietnam expected them to treat it as the senior state and follow its guidance. In turn, China believed it had a special relationship as well, in which both Vietnam would generally support Chinese policy, and, in particular, Chinese Communism against Soviet Communism.

The Vietnamese, however, had good reason to feel secure in their military power, if they ignored the political context.The People's Army of Viet Nam captured much of the equipment of the ARVN, and was now among the most experienced armies in the world. While its operations in 1975 did not show mastery of high-technology combined arms warfare, it became a very credible opponent, in direct combat, for forces lower in technology than the Warsaw Pact or NATO. While many of the personnel of the ARVN were purged or imprisoned, others eventually joined the new forces, bringing their expertise.

The PAVN had been growing for 40 years, and indeed reached its greatest size in 1976. PAVN infantry divisions were increased from 27 to 61 (48 regular infantry divisions and 13 smaller economic construction divisions), and military corps from six to 14. The Vietnamese Air Force was raised from three to five Air Divisions including one helicopter division. The Vietnamese Navy doubled the number of its combat vessels. [32]

Postwar Vietnam

According to Pike, in late 1990 about 500,000 had been demobilized from the PAVN (apparently to about 800,000 regulars and 1.6 million militia). Vietnam had to cope with huge destruction in both North and South, not only repairable damage to buildings and infrastructure, but much more difficult problems with unexploded ordnance and chemical contamination. [33]

Aside from the specialized tasks, the Vietnamese government did not have extensive experience with economic recovery. Their model was a centralized Stalinist one, which they themselves rejected with the introduction of doi moi Vietnamese-style markets, but not until 1986.

U.S.-Vietnamese immediate relations

While there is now considerable cooperation between Vietnam and the United States, the situation was tense immediately after the war.[34] As part of the Paris Peace Talks, there had been a 1973 agreement for aid to Vietnam, but Congress refused to fund it with language in in Public Law 94-41, a continuing appropriations resolution signed by President Gerald Ford in the summer of 1975. [35] A large part of the refusal centered on the issue, extremely sensitive in the U.S., of the fate of American military personnel held prisoners of war (POW), as well as those missing in action (MIA) in Vietnam. The first official U.S. mission to Vietnam, in 1977, was led by Leonard Woodcock, former head of the United Auto Workers and a representative of Jimmy Carter; his mandate was first to address the POW-MIA situation, and then explore aid; the Vietnamese were optimistic. In February 1977, "So certain of developing these ties were the Vietnamese that a group of oil executives visiting from Japan had been told in late 1976 that future development of Vietnam’s substantial petroleum interests “was reserved ‘for the American sector.’” “Washington, in turn, seems almost ready to accept the fact that the fate of most of the MIAs will never be known.”[36]

Prior to the Woodcock mission, there had been an unpublicized three-week trip by representatives of the World Bank and two separate missions by United Nations Development Program [UNDP]. Normalization of relations with the U.S. was seen as key; the UNDP told the Vietnamese that they alone could not fund the projects under discussions, additional donors would be needed, and the "Vietnamese know who the donors could be."[37]

Young suggests that a normalization between Vietnam and the United States, sought in 1977, might have reduced tension.

Several factors contributed to making normalization more difficult. The POW-MIA issue was extremely sensitive politically. Further, power, in the Carter Administration shifted between the U.S. Secretary of State, Cyrus Vance, and the National Security Adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski.

Vance's plans were broader, and included normalization with both China and Vietnam, a new arms control agreement with the Soviets, and a continued warming of the Cold War. Brzezinski's thinking was focused on the Soviets, and judged actions in how they could be used to pressure the Soviets. He sought a tilt to China as a pressure on the Soviet Union, and, if that annoyed the Vietnamese, whom he saw as Soviet puppets, it was fine with him. According to his aide Michel Oksenberg, Brzezinski despised the Vietnamese and called the "cesspool of civilization". Carter wrote in his diary that "He was overwhelmed with the Chinese. I told him he had been seduced."[38]

Richard Holbrooke had met with Vietnamese Foreign Minister Nguyen Co Thach at the Vietnamese mission to the United Nations, and, while they agreed in principle, Brzezinski continued to object. At the end of October 1978, normalization depended on conditions unacceptable to the Vietnamese, which, within months, were made moot by the Chinese invasion:

- Calming of hostilities between Vietnam and Cambodia

- Loosening of the alliance between the Soviets and Vietnamese

- Stopping Chinese emigration from Vietnam. [39]

Khmer-Vietnamese tensions

Since 1973, there had been skirmishes between North Vietnamese and Cambodian Communist Khmer Rouge units, both wanting the same Cambodian rice. In 1975, the Khmer Rouge captured all cities and towns, and drove the populace into the countryside, a self-genocide killing at least 1.5 million people.

From the Khmer standpoint in 1975, Vietnamese encroachments went back to .the Ly Dynasty of the Kingdom of Dai Viet, in the 12th century. More significant Vietnamese actions took place in the 17th through 19th century. Some Khmer Rouge radicals wanted to retake areas of the Mekong Delta, but their leaders would be satisfying with unilateral Cambodian definition of the border. The Cambodians certainly did not regard the Vietnamese as their superiors, regardless of the role that Vietnam may have played in creating the Kampuchean revolution. Vietnam saw Chinese aid to Cambodia as an encroachment in its sphere of influence. [40]

Cambodia, and the Khmer people, had been the Southeast Asian country least influenced by China. Like the Kingdom of Champa, they were more culturally Indic than Sinic. China had not historically considered Cambodia within its sphere of interest. [41]

While the world was not widely aware of the genocide inside Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge, supported by the Chinese and Americans as a check against the Vietnamese, were not only fighting the Vietnamese, but invaded Thailand in January 1977, killing dozens of civilians.[42] This raised little world outcry but intensified tensions in the region; the conflict between the Thais and the Cambodians is still little known.

Sino-Vietnamese tensions

Vietnam and China have millennia of conflict. There was cautious cooperation between North Vietnam and China during the Vietnam War, and China, after the fall of South Vietnam, believed it was time of a "show of gratitude" for its economic and military aid. That would include dealing with improved relationships, a tilt to China in the Sino-Soviet conflict, dealing with the problem of ethnic Chinese in Vietnam, the multipolar issues in Cambodia and border disputes. [43]

China had not appreciated the forced "Vietnamization" of Chinese in South Vietnam under Ngo Dinh Diem, but they had no friendly relationship with the South Vietnamese government.[44] The situation was much different in 1978, when Vietnam nationalized Chinese-owned businesses, pressured ethnic Chinese to evacuate border areas, and triggered a large-scale exodus of Chinese by land into China, and to anywhere as "boat people." [45] In response, China reduced aid to Vietnam, cancelling all in May 1978.

Britain, still in control of Hong Kong, sent boat people back to Vietnam. There were 57,000 Vietnamese in Hong Kong, of whom 13,000 were regarded as legitimate refugees. Douglas Hurd, the British Foreign Minister, said, "Vietnam has told us that those repatriated will not be punished for leaving," a statement doubted by many refugees. Thailand had over 11,000; there were 20,000 in Malaysia; and smaller numbers in Indonesia and the Philippines. British action, however, made many more refugees nervous that originally more receptive nations might change their policy and forcibly repatriate them.[46]

Third Indochina War (1978-1999)

A series of conflicts directly involving Vietnam, Cambodia, and China began to flare in 1978, which waxed and waned until a treaty in 1991, with small-scale actions until 1999. These have been called the Third Indochina War. Given the Vietnamese invaded with relatively high technology, were frustrated by guerrillas who had sanctuaries into which they could retreat, and that it seemed an endless war, cynics have called it "Vietnam's Vietnam". The action was "deplored" by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, (ASEAN) [47] with a statement from the then-chairman of the ASEAN Standing Committee, Indonesian Minister of Foreign Affairs Mochtar Kusumaatmadja; this became the ASEAN position. ASEAN members brought the matter to the United Nations Security Council.

In this situation, Thailand, an ASEAN member, was the "frontline state". ASEAN faced a problem of showing support for Thailand but Indonesia decided that the apparent strategy of prolonging the war and "bleeding Vietnam white", was not in the interest of Southeast Asia as a whole. It was believed that Thailand was providing sanctuary to the Khmer Rouge, frustrating the Vietnamese generals who were forbidden to pursue into Thailand, much as the Americans were not allowed to pursue the Viet Cong into Laos and Cambodia. [32] While always insisting on the central demand of Vietnamese withdrawal and Khmer self-determination, Indonesia encouraged the Khmers and Vietnamese and their external sponsors to a more stable settlement. Negotiations for such a settlement began in 1982, and ended with the Final Act of the Paris International Conference on Cambodia on October 23, 1991. Mochtar and the next Indonesian foreign minister, were key in these negotiations.

Cambodia, China, Thailand and Vietnam

In the autumn of 1983, the 95th PAVN regiment conducted what were termed 'training exercises' in Cambodia. On March 24, 1984, other PAVN units attacked Khmer Rouge headquarters, while the 95th Regiment crossed into Thailand to block the Khmer Rouge retreat. China responded with heavy shelling of towns on the Sino-Vietnamese border. [48] The PAVN withdrew from Thailand in early April, but the shelling continued, and the PAVN units in Cambodia continued until they overran the Khmer Rouge headquarters on April 15.

The Chinese then attacked toward the Laoshan hills on the border, fighting from May to July. In yet another irony, the Chinese headquarters was in Kunming, where the Viet-Minh had met with the U.S. Office of Strategic Services team during the Second World War.[49] The Laoshan area is considerably farther from Hanoi than was the 1979 attack, and the reasons for picking this site are not known. O'Dowd speculated that one reason may have been to draw PAVN troops out of Cambodia, just as the Battle of Khe Sanh may have been meant to draw U.S. troops away from the cities to be attacked in the Tet Offensive. China may also have wanted the psychological victory of capturing a provincial capital that could not easily be reinforced, Ha Giang City. The Chinese failed to take Ha Giang, and were beaten to a stalemate much as in 1979. [50]

As an example of the conflict, Peking Daily made the claim in a story about a local war hero identified as Xu Xiaodan, a scout for artillery units near Laoshan, a frequently reported flashpoint in the six-year-old undeclared China-Vietnam border war.[51] No exact date or Chinese casualties were given in the Associated Press report from 1985 report, which followed two days after a Vietnamese report forces killed 313 Chinese soldiers last month in repulsing "land-grabbing attacks" in its Ha Tuyen Province, which borders the Yunnan province of China. Smaller-scale artillery exchanges and border incidents between China and Vietnam ended in November 1991. [52]

A 1988 estimate put the PAVN at 1.2 million in the regular "main force" and 1.7 million in the militia or "para-military" force). A demobilization program planned to send 800,000 back to civilian life, still leaving a military establishment with 1.6 million personnel. Probably in June 1988, the Vietnamese decided to accept their losses and, with great ceremony, start withdrawing ground troops to let the Cambodians fight their own civil war.[32]

Normalization between Vietnam and the U.S.

President Bill Clinton, on July 11, 1995, announced that the U.S. agreed to full, mutual diplomatic relations with Vietnam. There was a consensus that both sides had made a reasonable attempt to solve the POW-MIA problem, with the understanding, except among POW-MIA activists, that there was no serious chance that live prisoners were being held, and work would go on to identify remains as they were discovered. Secretary of State Warren Christopher and Foreign Minister Nguyen Canh Cam signed the formal agreement.

The Vietnamese toned down some propaganda, renaming the Museum of American War Atrocities in Ho Chi Minh City the “Museum of War Evidence.” There were numerous joint meetings in Vietnam and the U.S., some digging into history, some a personal reconciliation of the combatants, and some both. [8]

U.S. mission to Vietnam

The first U.S. Ambassador was Pete Peterson, a former United States Air Force pilot who had been shot down over North Vietnam in 1966, and was a POW for 6 1/2 years. He returned, went into business, then became a Member of Congress. He served as Ambassador from 1997 to 2001.

At the Hanoi Roman Catholic cathedral in 1998, he married Vi Le, whose family fled to Saigon in 1954, moved to Laos in 1957, then to Thailand, and then to Australia. After training in banking and economics, she returned to Vietnam to set up bank operations in 1993. In 1996, Australia appointed her Trade Representative to Vietnam. She is now a U.S. citizen.

Vietnamese mission to the U.S.

Le Van Bang became the first Vietnamese ambassador to the U.S. in 1997, having served in a liaison office, then as charge d'affairs ad interim since 1995. He had been Ambassador to the UN since 1993, and a U.S. specialist in the Foreign Ministry between 1986 and 1992.

He is now Deputy Foreign Minister of Vietnam.

References

- ↑ Viet Nam is the more common spelling in Vietnamese, but the single word appears to be more common in English

- ↑ The 1946-1954 period of conflict is also sometimes called the First IndoChina War.

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley (1983), Vietnam, a History, Viking Press, p. 79

- ↑ Wiest, Andrew (2006), Introduction: an American War?, in Wiest, Andrew, Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land: the Vietnam War Revisited, Osprey Publishing, pp. 16-33

- ↑ Michael Lind (1999), Vietnam, the Necessary War: A Reinterpretation of America's Most Disastrous Military Conflict, The Free Press, pp. 10-11

- ↑ An enabling Party resolution was passed in January, but this was the date of starting to build infrastructure; combat use of that infrastructure was still two or more years away

- ↑ , Chapter 6, "The Advisory Build-Up, 1961-1967," Section 1, pp. 408-457, The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Volume 2

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Moore, Harold G. (Hal) & Joseph L. Galloway (2008), We are soldiers still: a journey back to the battlefields of Vietnam, Harper Collins

- ↑ Eckhardt, George S. (1991), Vietnam Studies: Command and Control 1950-1969, Center for Military History, U.S. Department of the Army, pp. 68-71

- ↑ Bui Tin (2006), Fight for the Long Haul: the War as seen by a Soldier in the People's Army of Vietnam, in Wiest, Andrew, Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land: the Vietnam War Revisited, Osprey Publishing, p. 55

- ↑ William Colby, Lost Victory, 1989, p. 173, quoted in McMaster, p. 165

- ↑ Kenton Clymer (2006), The War outside Vietnam: Cambodia and Laos, in Wiest, Andrew, Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land: the Vietnam War Revisited, Osprey Publishing, pp. 102-104

- ↑ Jeffrey Grey (2006), Diggers and Kiwis: Australian and New Zealand Experience in Vietnam, in Wiest, Andrew, Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land: the Vietnam War Revisited, Osprey Publishing, pp. 156-158

- ↑ Rick Ryan, AATTV Association, A brief history of the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV)

- ↑ Halberstam, David (1972), The Best and the Brightest, Random House, pp. 121-122

- ↑ Thomas, Evan (October 2000), "Bobby: Good, Bad, And In Between - Robert F. Kennedy", Washington Monthly

- ↑ Doris Kearns and Merle Miller, quoted in Karnow, p. 320

- ↑ McMaster, H.R. (1997), Dereliction of Duty : Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam, HarperCollins, ISBN 0060187956

- ↑ Curtis Peoples (April 1999), The Role of Third Country Forces in Vietnam, McNair Scholarship Program, Texas Tech University

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ted Engelmann (October 2006), "Examining the seven-flag Chieu Hoi pass: a primary document from the American war in Viet Nam", Social Education

- ↑ Grey, p. 159

- ↑ Carlson, Justin, "The Failure of Coercive Diplomacy: Strategy Assessment for the 21st Century", Hemispheres: Tufts Journal of International Affairs

- ↑ Morgan, Patrick M. (2003), Deterrence Now, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Henry Kissinger (1973), Ending the Vietnam War: A history of America's Involvement in and Extrication from the Vietnam War, Simon & Schuster, p. 50 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Kissinger" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Karnow, p. 582

- ↑ Kissinger, p. 50

- ↑ Kissinger, pp. 27-28

- ↑ Kissinger, pp. 249-250

- ↑ Grey, p. 159

- ↑ Military History Institute of Vietnam, Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954-1975 (2002), Hanoi's official historyexcerpt and text search

- ↑ Shulimson, Jack, The Marine War: III MAF in Vietnam, 1965-1971, 1996 Vietnam Symposium: "After the Cold War: Reassessing Vietnam" 18-20 April 1996, Vietnam Center and Archive at Texas Tech University

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 , Hanoi/Viet Cong View of the Vietnam War, Fourteenth Military History Symposium, "Vietnam 1964-1973: An American Dilemma.", U.S. Air Force Academy,, October 11-19, 1990

- ↑ Myron Allukian Jr. and Paul L. Atwood (2000), Public Health and the Vietnam War, in Barry S. Levy, Victor W. Sidel, War and Public Health, American Public Health Association, ISBN 0875530230, pp. 215-219

- ↑ Marilyn B. Young (1991), The Vietnam Wars 1945-1990, HarperCollins, pp. 301-303

- ↑ Mark E. Manyin (February 11, 2005), U.S. Assistance to Vietnam, Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, CRS Order Code RL32636, p. 6

- ↑ Edwin Anton Martini III, Invisible Enemies: the American War on Vietnam, 1975-2000 I, doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, pp. 128-134

- ↑ Martini, p. 136

- ↑ Young, pp. 308-311, citing Kelvin Rowley & Grant. Evans, Red Brotherhood, (Versio, 1984) and Nayan Chandra, The War after the War: a History of Indochina Since the Fall of Saigon (HarcourtBrace Javanovich, 1986)

- ↑ Young, pp. 309-310

- ↑ Young, p. 305

- ↑ Pao-min Chang (1985), Kampuchea Between China and Vietnam, NUS Press, pp. 1-3

- ↑ William Shawcross, The Quality of Mercy: Cambodia, Holocaust and Modern Conscience, (Simon & Schuster, 1984), cited by Martini, p. 180

- ↑ Young, p. 305

- ↑ "500,000 Uncles", Time, May 13, 1957

- ↑ Allukian & Atwood, p. 225

- ↑ Robert Pear (December 20, 1989), "Hong Kong's Move Worries Refugees Elsewhere", New York Times

- ↑ , Indonesia, ASEAN, and the Third Indochina War, Indonesia Country Studies

- ↑ O'Dowd, Edward C (2007), Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War, Routledge, p. 98

- ↑ Patti, p. 3

- ↑ O'Dowd 2007, pp. 99-100

- ↑ "Peking Says a Clash Left 200 Vietnamese Dead", Associated Press, August 5, 1985

- ↑ O’Dowd, Kenneth W. & John F., Jr. Corbett (July 2003), The 1979 Chinese Campaign in Vietnam: Lessons Learned, in Laurie Burkitt, Andrew Scobell, Larry M. Wortzel, The Lessons of History: The Chinese People's Liberation Army at 75, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College,p. 362}}