Fossil

The word fossil is derived from the Latin fossilis, something dug up.[1] During the Middle Ages, the term ‘fossil’ was used for any sample recovered from the Earth, including rocks and minerals.[1] Today, fossils are recognised as any record of ancient life. They can be actual remnants of an organism, or evidence of their last behaviour.[1]

Overview

Fossils represent a very small proportion of all the organisms which have ever lived. This is because fossils only form under specific conditions. Decomposition is a requirement for environments to function. It follows that fossilization represents a deviation from this natural process.[1] Any plant or animal needs to pass through a number of stages to become a fossil.[2] First, the organism must become deposited in sediment. Once it is buried, it may begin to undergo diagenetic processes. Diagenesis is simply any change, chemical or physical, which occurs in an organism after burial.[2] Such changes are necessary for preservation because organic matter will not survive for long before it is decomposed. However, older fossils are more likely to have been modified by diagenetic processes, and thus, to be a less accurate copy of the original”.[3] A more detailed explanation of how and why fossils form can be found in the article fossilization.

Different types of fossils

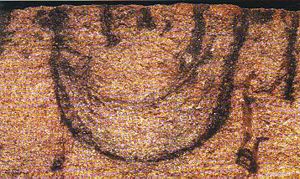

Fossils can be formed in a number of ways. The mineral replacement of shell or bone is called petrification, because it turns organic material into stone.[4] An organism can leave a mould behind when it decays, preserving surface detail in the surrounding sediment. If the mould later fills with sediment, an external replica of the organism is created called a cast. A cast does not preserve the internal structure of the original organism.[1] Trace fossils are not remnants of an organism itself, but some record of its last behaviour. Tracks, burrows, coprolites (fossil faeces) and stone tools are all examples of trace fossils.

Any animal or plant has the potential to become a fossil, although this depends to a certain degree on its makeup. Soft-bodied organisms are preserved, although they are much rarer than fossils of hard parts. Plant fossils are usually not intact, because various structures of a plant are inclined to fall off during its lifetime. This creates separate fossils of the different parts.[4] The most common fossils are bones and teeth.[5]

Famous Fossils

There are some very famous fossil hominins from South Africa, namely the Taung Child, Mrs Ples and Little Foot.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 MacRae, C.S. 1999. Life Etched in Stone: Fossils of South Africa. The Geological Society of South Africa, Johannesburg.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Brett, C.E. & Baird, G.C. 1986. Comparative Taphonomy: A Key to Paleoenvironmental Interpretation Based on Fossil Preservation. PALAIOS 1(3): 207-227.

- ↑ Allison, P.A. & Briggs, D.E.G. 1991. Taphonomy: Releasing the Data Locked in the Fossil Record. Plenum Press, New York.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 McCarthy, T. & Rubidge, B. 2005. The Story of Earth and Life: A southern African perspective on a 4.6-billion-year journey. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

- ↑ Shipman, P. 1981. ‘’Life History of a Fossil: An Introduction to Taphonomy and Paleoecology’’. Harvard University Press, England.